Leigh Bowery, 1988

Leigh Bowery, 1988Photo: Fergus Greer

The 1990s was the decade of Queer. Mobilised as an identity category that refused categorisation as much as it refused identity itself, ‘queer’ was especially potent in the way it ushered in a wave of queer cultural production, especially in the visual arts and cinema. One of the great promises of queer, at this time, was that it reinvented representational concepts of transgression, subversion, playfulness, and pleasure. At its transgressive best, queer glowed like radium ready to contaminate a dominant culture that had originally invented the term as a homophobic slur.

As with any subcultural category, queer lost its way and a gnawing suspicion hovers that its relevance has diminished. Queer’s dumbing down (or dressing up, depending on your perspective) during this decade is owed in large part to the mainstream (and male specific) invention of the metrosexual – a term riddled with straight anxieties about claiming a corner on queer style, as if queer is inherently about style and nothing else. But as quickly as the metrosexual emerged across the posturing brandscapes of contemporary media culture, it too seemed destined for the dustbin, surely to be replaced with new terms that shape identity as much as they point to its neurotic inability to understand itself.

It’s time we returned to the moment of queer’s inception, if not to reclaim it verbatim, to at least revisit its critical power for rethinking, indeed remembering, the reason it came into being in the first place: to oppose the selfsame heteronormativity that has crept into contemporary homosexual cultures, rendering them dull, vapid and commonplace. The general move towards political conservatism in Australia and elsewhere has pushed aside subcultural expressions of queer as if the war for equality or acceptance was won once queer was coopted or dissipated by the mainstream. When Pope Benedict attacked homosexuality in December 2008 as a threat to the “ecology of man”, it surely stands to reason that the war is far from over.

The push towards gay marriage; access to adoption, surrogacy and IVF; as well as the desire for acceptance within the Church – despite the naggingly simplistic rhetoric of equal rights – makes queers unqueer; the struggle for recognition comes at a price by obliterating difference in favour of heteronormative sameness. The uncritical replication of those oppressive structures that made us invisible for so long has erased queer, making it a complacent shadow of its former self. The allure of queer was its critical embrace of marginality and difference, its elusive resistance to definition and closure, the way it ushered in new representational dialogues and debates. Claims that queer is dead only have weight if we give in to the ever deepening conservatism and political inertia gripping us at present.

Queer visual and performing arts have a significant history in Australia that continues to flourish, even if it continues to negotiate contentious and circuitous questions as: What makes a queer artist? What makes an artwork particularly queer? Since the 1980s, a groundswell of Australian artists including Juan Davila, William Yang, Philip Juster, David McDiarmid, Peter Tully, Scott Redford, Gary Carsley, Deborah Kelly, Linda Dement, Aña Wojak, Christine Dean, Luke Roberts, Michael Butler, Kurt Schranzer, r e a and Brook Andrew, among many others, have made notable contributions to queer visual arts in Australia. Younger generations of artists, such as The Kingpins, José Da Silva, Liam Benson, Anastasia Zaravinos and George Tillianakis, the latter three artists hailing from Western Sydney, are presently breathing new life into how we understand queer aesthetics through performance work owing a large debt to Leigh Bowery, who hailed from a suburb in Melbourne called Sunshine.

Australia’s most legendary queer artist, Leigh Bowery took the UK by storm not long after moving there from Australia in 1980 with the thrill-seeking purpose of becoming famous and notorious. When he died from AIDS on New Years Eve in 1994, Bowery had left behind a body of work primarily based around his own body. He was frequently described as a living canvas for outlandish fashion designs that were important because of how they reinvented the language of drag. The ephemeral character of his work befits the ‘here today gone tomorrow’ vortex of club land, where Bowery’s attention seeking antics were first noticed. Unlike many dead artists whose impact is measured by the collections that feature them, the monographs memorialising them, or the auction prices that fetishise them, there is a sense that Bowery’s legacy exists in dreams, being the stuff of subcultural myth. Certainly the landmark exhibition Take a Bowery, curated by Gary Carsely for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, in 2003/04, signposts the manner in which his work was marked by transience; trawling through the remarkable collection of costumes, accessories, shoes, films, photographs, paintings and archival material at the time was like watching morning materialise after the party from the night before. What remained when Bowery died was an innovative collection of queer couture, which without Bowery feels oddly obsolete because the performance of adorning the clothes – the specificity of Bowery’s body whipped into submission by his often figure-altering garments – is what made them so legendary. If anything, the film, music and photographic collaborations Bowery engaged in with Charles Atlas, Cerith Wyn Evans, Fergus Greer and Lucien Freud thankfully document his body at work, providing a snapshot of a decade where AIDS loomed large – a time that shaped the way we comprehended the cultural discourses of queer performativity emerging during Bowery’s last days.

Bowery’s impact in Australia is particularly evident due to his influence on artists like the late Brenton Heath-Kerr in the late 1980s or the current generation of queer performance artists. The Kingpins are an obvious case in point. Established in 2000 after winning a Drag King contest, The Kingpins comprise four young women artists (Angelica Mesiti, Técha Noble, Emma Price and Katie Price) who play dress-ups with garb stolen from the testosterone-fuelled time capsules of contemporary popular culture. Their video installations, performances, costumes, assemblages, paintings and merchandise sample and remix the seeming disparity between corporate and celebrity culture, expanding the language of music video through multi-channel gallery installations that use humour to discharge understandings of gender in a post-identity world. One of their early works Versus (2002) is a ‘collaboration’ with Leigh Bowery via the short-lived music group he formed in the early 1990s with Sheila Tequila and Stella Stein called Raw Sewage. Shot in a video booth in Piccadilly Circus, Raw Sewage’s Walk this Way (1993) is a hilarious performance set to the eponymous Aerosmith/Run DMC hit. In Versus, The Kingpins also perform the song, but in response to Raw Sewage (which is seen on a grid of television screens displayed on set) as much as it is a response to the intense machismo originally imparted by Aerosmith and Run DMC. Versus was first shown in Cerebellum at Performance Space, Sydney, a significant queer exhibition, again curated by Gary Carsley, and featuring Bowery in collaborations with Raw Sewage and Charles Atlas, alongside the work of Monika Tichacek, whose dark video installation Lineage of the Divine (2002) featured notorious New York drag diva Amanda Lepore – a present day Leigh Bowery if ever there was one.

Drag is an important aspect to Gary Carsely’s work as an artist, though unlike his curatorial work which champions innovative uses of drag in performance art, Carsley sees drag as a rhetorical strategy that applies more broadly to cultural and national identity. ‘Australia is a drag culture’ claims Carsely, and by this he is referring to a performance of national identity that lip-syncs to the seductive lure of more international cultural refrains. Carsley invented the ‘draguerreotype’ to describe work he has been making in recent years. Expanding Daguerre’s 19th Century photographic monotype process by manipulating digital photos of famous parklands with layers of laminated wood grain foils, Carlsely complicates notions of originality through reproduction. In his essay ‘A Small History of Photography’, Walter Benjamin, whose famous theories of mechanical reproduction have lingered for almost a century, notes that daguerreotypes require ‘proper light,’ are ‘one of a kind,’ and are ‘kept in a case like jewellery.’ Carsley, whose use of light and dark helps ‘drag nature’ away from itself, subverts claims to any ‘one of a kind’ originality through ‘value added’ surface effects that hurl nature into a queer performance of itself – jewellery optional. The title of his Art Gallery of NSW exhibition, Scenic Root (2007) is a witty pun on how the frequent use of such parks for public sex between men mystifies these abstracted landscapes into queer representational realms.

Carsley’s work functions almost like digital collage, where the ‘singularity’ of the image is refused in favour of an image made up of almost imperceptible layers. Before performance artists like The Kingpins – whose remix, mash and sampling elicits montage in motion – the two dimensional cut and paste practice of collage was at home in the work of leading queer artists like Scott Redford and Kurt Schranzer. The reconstitution and recycling of existing images, otherwise destined for the trash, imbues collage with a melancholy that is particularly queer. The collage work of Redford, who continues to be one of Australia’s most uncompromising queer artists, simultaneously worships and undermines popular culture’s homoerotic icons. Like an obsessively collaged high school folder featuring cut out male magazine pin-ups, Redford’s conceptual collages invert the precise logic underpinning modernist applications of collage, while appearing strangely grounded in a boy’s own almanac of queer desire. Schranzer uses collage in overtly modernist ways, combining machine parts from industrial treatises from the early 1900s with meticulous line drawings that reveal the artist’s fetishistic investment in his subjects. Male bodies are seductively tangled with organic life forms and mechanical / medical contraptions in an attempt to zone in on the erotic, something not often associated closely with modernist aesthetics. Schranzer’s exhibition Le cul mécanique (‘the mechanical arse’) at Esa Jäske Gallery in 2006 featured drawings of nude skateboarding youth, their anuses substituted for a collaged machine part. Like Redford, Schranzer’s work can be challenging for viewers unused to a consistently overt negotiation of queer archetypes and aesthetics.

Similarly, Luke Roberts occupies difficult territory as an artist and he knows it. Originally from Alpha, an outback town in Queensland, Roberts has carved out a career where his outlandishly landless alter ego of more than 30 years, Pope Alice, out-famed his other practice as a painter and installation artist. Roberts’ outback upbringing has contributed to his ongoing engagement with marginality in regional as well as sexual and spiritual contexts. It is perhaps his more recent identification with the Raelien Movement that adds another frequently misunderstood or dismissed dimension to his practice. (I sat on a conference panel with him in 2008 and a famous lesbian separatist feminist who was also scheduled to speak, was quick to dismiss him – in fact when she wasn’t rolling her eyes, she refused to acknowledge his presence). Extra terrestrials and UFOs have been recurring motifs of otherness in his work – only now are they becoming more fiercely attached to a working methodology that constructs fictions for his multiple personalities at the same time as these fictions are strategically institutionalised as truths. In recent work, Roberts temporarily sets aside the spiritual and ‘sacred feminine’ in lieu of oppositionally queer readings of masculinity. In one series, Roberts performs as Warhol as Hitler (a response to what has been perceived as the ‘de-gaying of Warhol’ [see Doyle, Flatley & Muñoz's anthology Pop Out: Queer Warhol, 1996]. Another body of work in development draws upon ‘cowboy’ and ‘Indian’ stereotypes and the feminising of queer through the colour pink, to interrogate childhood sexuality.

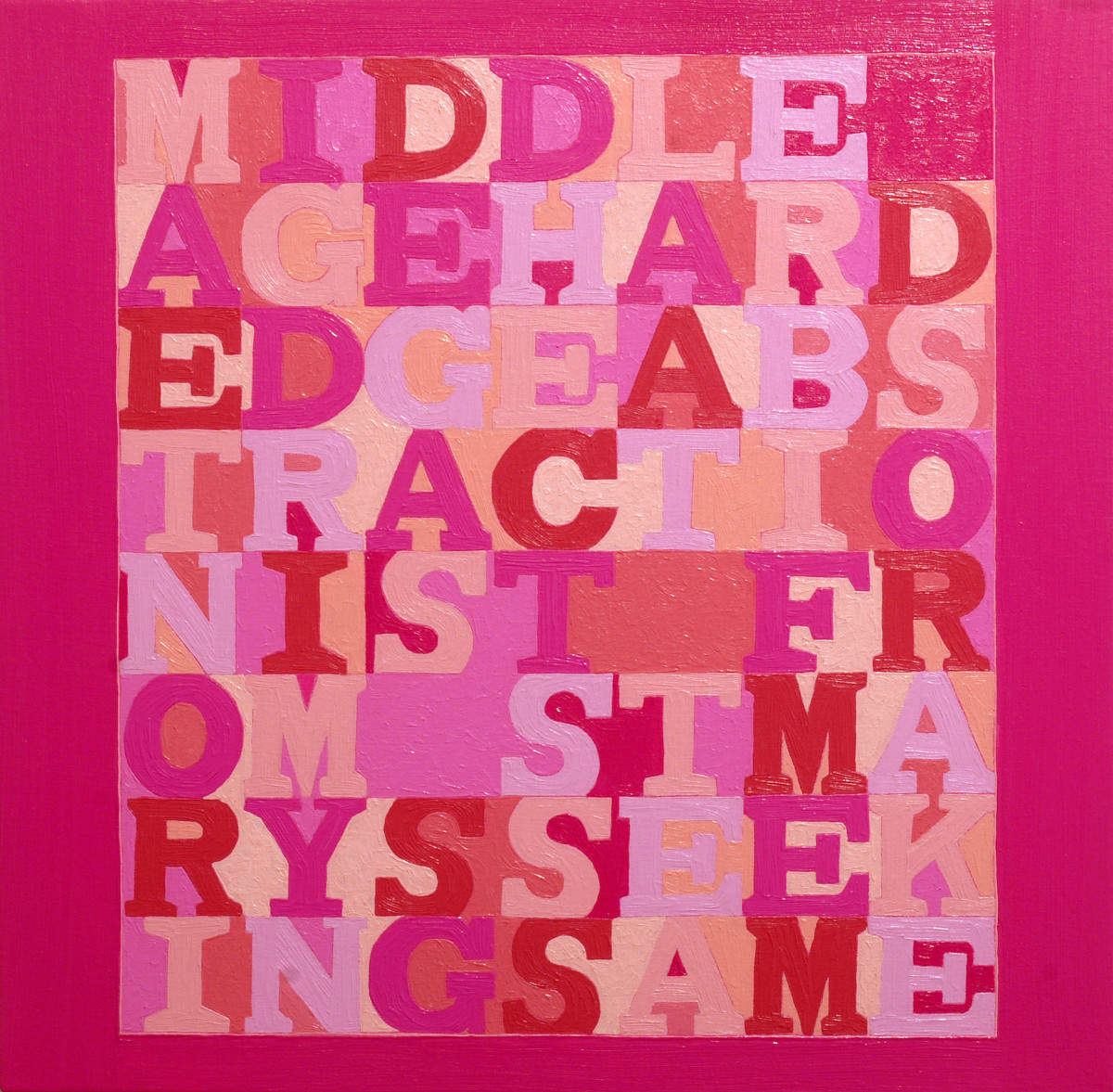

Destabilising the arbitrary gender coding of pink has been a longstanding project for Christine Dean. Rewriting modernism, masculinity and pinkness through the monochrome, Dean is a rigorous visual and textual researcher who wreaks havoc with the normative processes animating compulsory heterosexuality and its queer undoing in suburbia. According to Dean, pink is the forgotten colour in the history of abstract painting, evidenced by Barbara Rose omitting it from her book Monochromes: From Malevich to the Present (2006). Forgotten or overlooked histories are foregrounded in Dean’s paintings through the quoting of found textual fragments that iron out the non-representational character of the monochrome through their very ‘readability’. For Dean, the use of language in her paintings complicates the binary of abstraction/representation to ‘queer’ effect. She says, ‘Similarly, queer attempted to step outside of the binary and even if it failed, at least it tried and was a step in the right direction.’ Despite her suggestion that queer has on some levels ‘failed’, it is not necessarily an unproductive malfunction. Dean forecasts, and rightly so, that ‘Queer has a much bigger future than people can ever begin to predict – its seeds in critical thinking give it a much bigger shelf life than we can imagine.’

Christine Dean, Middle Age Hard Edge Abstractionist from St Marys Seeking Same, 2007

Christine Dean, Middle Age Hard Edge Abstractionist from St Marys Seeking Same, 2007Essay for Art & Australia

Published by Art & Australia, issue 46:4 in 2009.