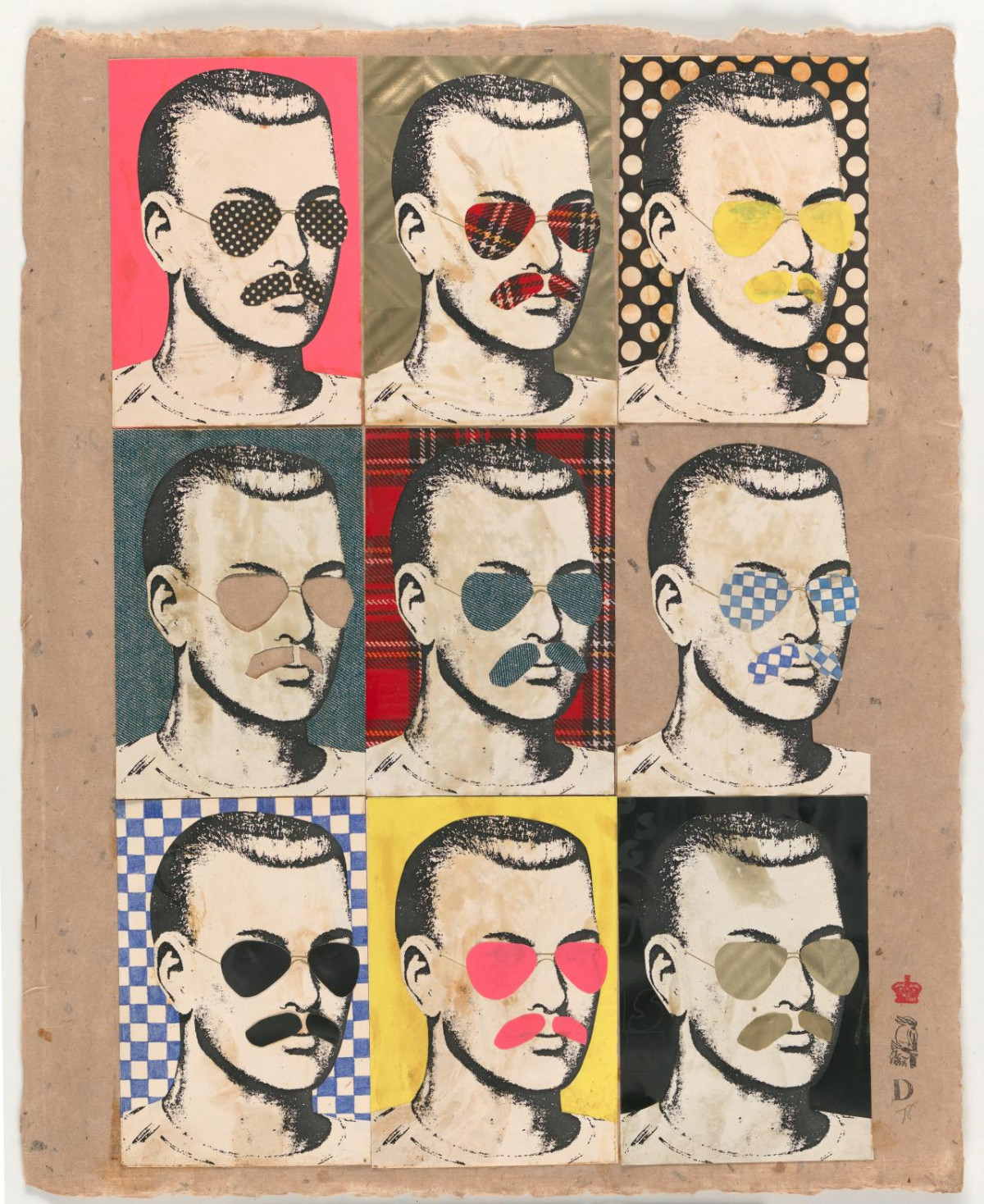

David McDiarmid, Strangers in the Night, 1978

David McDiarmid, Strangers in the Night, 1978Collection: National Gallery of Victoria

My priority as an artist has always been to record and celebrate our lives. Having lived through an extraordinary time of redefinition and deconstruction of identities, from camp to gay to queer; and seeing our lives and histories marginalised every day, we have a responsibility to speak out.

— David McDiarmid

From ‘A Short History of Facial Hair’, a paper presented at an HIV research forum in Melbourne in 1993 – two years before his death from an AIDS-related condition – the impassioned urgency of these sentiments perfectly exemplify the art and politics of David McDiarmid. It is as if he was also forecasting the way in which his own artistic legacy has posthumously railed against being marginalised as a footnote in Australian art history. Curated by longtime friend and executor to his estate, Dr Sally Gray, the exhibition When This You See Remember Me had its fair share of ‘marginalisation’: in fact, it almost didn’t happen. In the planning stages for almost two decades, and after much institutional argy-bargy, the show thankfully did go on, with the current guard at the National Gallery of Victoria clearly understanding and committed to its importance.

Presenting the visual relics of a life absorbed by art, design and activism from the early 1970s until the mid-1990s, the exhibition was particularly enriched by voluminous ephemera and archive material loaned by friends, former lovers and fellow provocateurs. The contents of the long vitrine lining the wall of the first space heralded the historical importance of the subject. Humorous and melancholy, these documents fleshed out the social and historical context of an era almost decimated by HIV/AIDS but held together on a knife’s edge by the cogent political activism of this time and its attendant visual culture.

Perhaps the most important pioneering figure from this period, McDiarmid’s work recontextualised and ‘queered’ mainstream popular culture through its juxtaposition with or references to gay porn, disco, fashion and music. Though friends like Peter Tully and Bill Morley occupied the same creative space, McDiarmid was, as Gray notes in her catalogue essay: ‘the first Australian artist to exhibit explicitly “out” gay political art and the first Australian gay man to be arrested in the course of fighting for gay rights.’

Early ‘out’ works from Secret Love, McDiarmid’s first solo exhibition at Sydney’s Hogarth Galleries in 1976 adorned the walls of the first room, complementing archival material that, by its personal nature, also spoke to other ‘secret loves’. Surprisingly, these works and others assembled for the show (especially those from private collections) have survived well given the seemingly ephemeral nature of much of what he did – borrowed, as it was, from mass and hence disposable culture.

The exhibition journeyed through McDiarmid’s vibrant mosaics and laser-cut holographic collage works, including the kaleidoscopic Disco Kwilt series, which was made in the late 1970s and early 1980s in New York when McDiarmid was immersed in the feverish beats and amphetamines of the Paradise Garage nightclub. His sexually explicit safe-sex campaign posters for ACON still pack a punch today – looking at these images years on, it’s no wonder McDiarmid is often likened to Australia’s Keith Haring equivalent (of sorts). Equally intense in their lurid palette and urgent politics was McDiarmid’s final body of work, the now widely reproduced Rainbow Aphorisms series, plastered all over the final room of the exhibition.

Coinciding with the 20th International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, this remarkable exhibition was as timely as it was long overdue. In reality McDiarmid is just the tip of the iceberg of queer artists yet to receive similar institutional recognition. And that’s because ‘queer’ can unintentionally suppress itself in its groundless emphasis on fluidity and change. Part of the danger of queer is that its own terms of reference can shift so quickly that important cultural and visual histories like this one can run the risk of being lost. A figure such as McDiarmid occupied this shifting, ephemeral ground all the more because his work has also been classified as ‘decorative art’, which has at times further suppressed its importance in art-historical discourse.

‘Hand and heart shall never part, when this you see remember me’ is a Valentine’s Day homily quoted in McDiarmid’s work. Adapted as the title of the exhibition, the call to remembrance may have been focused on McDiarmid’s life and work. And yet in remembering this person I never knew, I’m remembering, by implication, a whole lot more.

David McDiarmid, Disco Kwilt, 1981

David McDiarmid, Disco Kwilt, 1981Collection: Artbank. Gift of Bernard Fitzgerald

Review of When This You See Remember Me at National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 9 May – 31 August 2014.

Published by Art Monthly Australasia, issue 273 in 2014.