Daniel Mudie Cunningham, William Yang in Repeats, 1999-2000

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, William Yang in Repeats, 1999-2000Hi … This is William Yang here. I got your letter about your project and I’d be happy to participate. However, there is a bit of a trade-off: if you’re going to take my photograph, then I’d like to take your photograph. I think, um, nude in the jacuzzi would be good for you. However, you may not take my photograph nude – but we can talk about that later. Okay, see you. Bye.

— William Yang, message left on author’s answering machine, 1999

Gay and lesbian liberation in Australia has its roots in the 1970s – due in large part to the goalposts historians erect on the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City as a marker for the emergence of gay political and sexual freedom in the western world. But it was during the 1990s when that sexually heady, MDMA-fuelled world which peaked around parties and parades was critically regarded in categorically loaded terms around an idea of ‘queer’.

Previously regarded a pejorative term, ‘queer’ was mobilised as an identity category that refused categorisation as much as it resisted identity itself. Paradoxically, a post gay/post-lesbian generational demarcation of difference is what helped establish queer in the nineties, regardless of whether the assertion of new sorts of labels was resisted.

‘Queer theory’, ‘queer cinema’, ‘queer performance’, ‘queer literature’, ‘queer art’: It was a time when it was not uncommon or unsurprising for queer voices to emerge across diverse disciplines and discourses and assert its cultural production as decidedly queer. Phaidon’s recent tome Art and Queer Culture (2013), self-described as ‘the first book to focus on the criticism and theory regarding queer visual art’, surveys leading international figures such as Felix Gonzales-Torres and Catherine Opie. Aside from Juan Davila, however, the wealth of Australian queer art is sadly overlooked.

The queer sphere of the nineties saw the annual Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade explode as a spectacular tourist event, with its accompanying cultural festival packed full of dynamic queer art exhibitions, ranging from DIY, grass roots or artist-run affairs to the institutionally supported events.

In photographic terms, the most consistent chronicler of the queer scene in Australia was and, to an extent, still is William Yang (though a new generation of photographers including Samuel Hodge, Paul Knight and Drew Pettifer are Yang’s aesthetic descendants). Leaving Brisbane in 1969 to live in Sydney, Yang’s arrival ‘coincides with the beginning of the post-Stonewall gay movement in Australia’, as he writes in Friends of Dorothy:

I don’t think I ever made a conscious decision to come out; I was swept along by the tidal wave of change that occurred at the time. I have seen many events in the movement’s history although in the early seventies I did not take photographs like I do now.

The ‘now’ of then is 1997, when Yang’s book Friends of Dorothy (and its accompanying exhibition at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery) was published. In it Yang provides a ‘cobbled together’ or ‘haphazard’ (his words) account of Sydney’s queer community. Though this history he focuses on the pre-nineties, post-Stonewall world of Sydney’s gay and lesbian community, it accelerates alongside the growing acceptance and mainstreaming of queer that occurred during that decade. For Yang, the queer scene is political, communal, celebratory and, above all, friendly. It is not defined by individual identity but, rather, by whether one is, or is not, ‘Dorothy’s friend’ – an expression deriving from the perceived campness of Judy Garland’s insouciant character in The Wizard of Oz (1939). It is also another Stonewall reference in that the grief stemming from Garland’s death and funeral is often said to have been a backdrop for the riots.

Friends of Dorothy chronicles queer life and times in Sydney. What this publication represents is a private diary in the form of a photo album, a genre that privileges implication, revelation and disclosure. Yang’s essential aesthetic categories are the casual collective and the contrived portrait. In the former, he captures the mood of nightclubs, sex parties, literary gatherings, exhibition openings and the like. Many images seem to reflect, or comment on, the preoccupation that queer culture supposedly has with appearance, especially its own.

Though Yang’s testament is a striking one, it does not match the power of his previous collection, Sadness (1992), which documented the impact of AIDS on the queer community. In Friends of Dorothy, AIDS is a hollow spectre that haunts the excess that constitutes gay culture.

Yang’s success as a photographer has been the tension he maintains by aligning seemingly unstaged casual documentary snapshots with staged portraiture. As a performance artist who has transformed his images into monologue-based slideshows, the stage has an even greater, more literal resonance. The ‘unstaged stage’ of his practice became even more complex and compelling in the nineties when he started augmenting visual narrative with handwritten stories adorning the surface of the photographic image. As Russell Storer has written: ‘This hindsight and recontextualisation is typical of Yang’s employment of photographs as a form of diary’.

And that is what I did to William in 1999.

William Yang, 'The younger photographer photographs the older photographer', Outrage, no. 189, February 1999.

William Yang, 'The younger photographer photographs the older photographer', Outrage, no. 189, February 1999.I first met William at a dinner that followed an exhibition opening at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1996. I was at this dinner with my then-boyfriend Chris. William seemed very curious about us; later I realised this was because Chris is Chinese. I would see William around the art and gay scene from time to time and we always showed an interest in each other. William liked that I had written about his work – these articles appeared in Photofile, Sydney Star Observer and IF Magazine.

In early 1999 I started working on an art project called Repeats. The final product was a video incorporating a soundtrack of answering machine messages, each one accompanied by a sequence of stylised photographic stills featuring the person who left the message. I wrote to William inviting him to be part of the project. William agreed to participate if he could take my photograph, preferably in the nude. He made it clear from the outset I couldn’t take his photograph nude. To his delight I agreed to be ‘taken nude’.

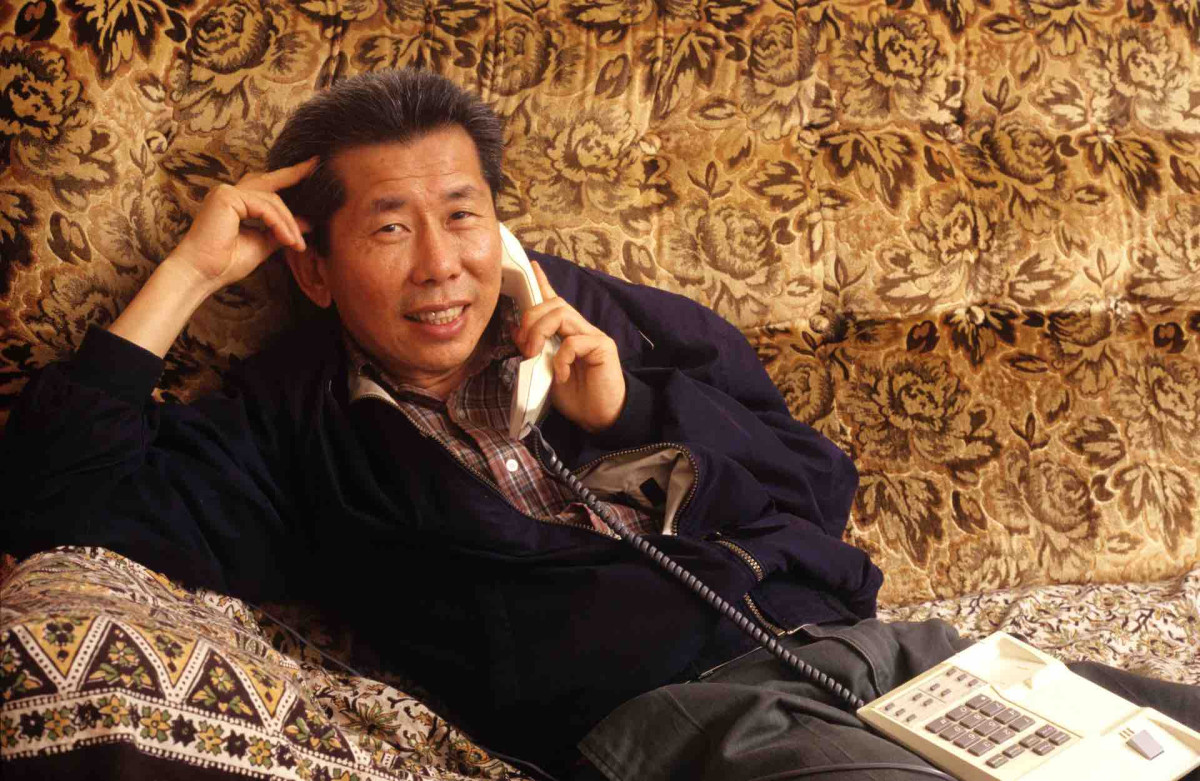

On the day of the shoot, I caught a bus over to William’s Bondi apartment armed with my camera gear. We both set up our cameras on tripods. The resulting photograph depicts me naked photographing William who was seated on his couch, pretending to be on the phone. William’s camera recorded the scene; so did mine. William published his version of the photo in the gay magazine Outrage alongside a caption reading: ‘The younger photographer photographs the older photographer.’

The outcome of the shoot: two photographs of the same thing; two different ways of telling the same story.

Soon after, William rang me up and said he wanted to photograph me again. Sure, why not? Since I’d seen William I’d broken up with Chris and had dyed my hair blond – not necessarily related milestones. The night before this second shoot I’d been out dancing at a club until some ridiculous hour, so I was feeling very hung-over. But a promise is a promise. So I went to William’s place and he photographed me nude a second time. Among the various poses, he wanted to re-photograph the scene of me in the nude photographing him while he was on the phone. He wanted a version of the photo with my newly blond hair. ‘Most people know Daniel as a serious art critic however I’m busily reconstructing him as a bottle-blonde bimbo, which sort of turns him on because it subverts people’s expectations of him. He’s queer that way,’ wrote William later on the photograph.

During this shoot I wasn’t actually taking any photos of William for my art project – I’d achieved what I’d wanted from him the first time around. As for William, a photographic series of portraits about me was starting to form.

William was quite curious about my breakup with Chris; our conversations often centred on whether would I date more Chinese men in the future. He invited me out a few times and I enjoyed being his plus one; in my mind these dates were platonic and grew out of an art ‘trade-off’. When later that year I started dating Drew, a white guy my own age, William expressed his disappointment and told me I’d become ‘safe’, which hurt my feelings. It was then I realised William had something of a crush on me. I’d just gotten an email account – it was 1999 remember – so I wrote William an email to tell him how I felt:

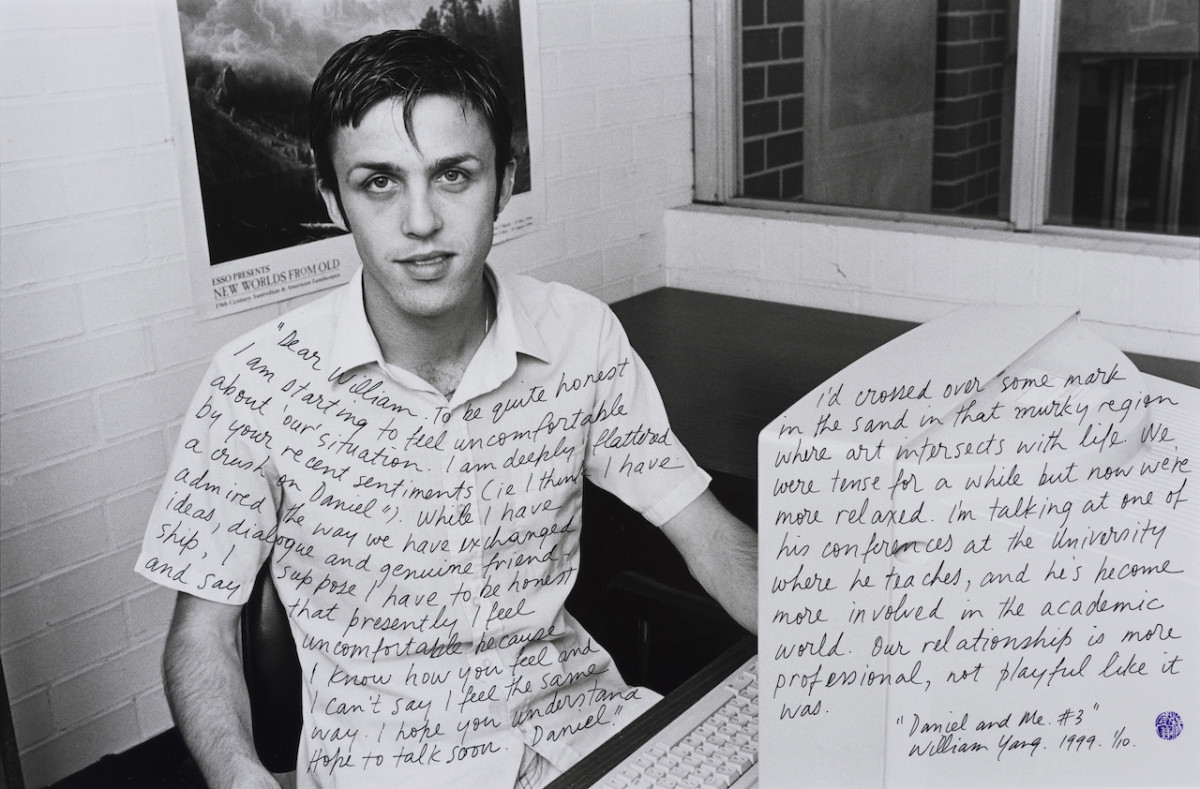

Dear William. To be quite honest I am starting to feel uncomfortable about ‘our’ situation. I am deeply flattered by your recent sentiments (ie. ‘I think I have a crush on Daniel’). While I have admired the way we have exchanged ideas, dialogue and genuine friendship, I suppose I have to be honest and say that presently I feel uncomfortable because I know how you feel and I can’t say I feel the same way. I hope you understand. Hope to talk soon. Daniel.

William responded by asking if he could photograph me one last time. I was teaching art history at the University of Western Sydney, where I had just enrolled in a Cultural Studies PhD. William hoped it would be okay if he came to my office at the Kingswood campus and take photos there. It was obviously important to him to stage the final photograph in my office, where I would be clothed and be more ‘serious’ because it was the logical end-point of our exchange. After this series of photo shoots was complete William showed me the photos, which revealed descriptions of our exchange through his trademark hand-written text on the photos. On the final photograph he had transcribed my email to him, followed by his own observations:

I’d crossed over some mark in the sand in that murky region where art intersects with life. We were tense for a while but now we’re more relaxed. I’m talking at one of his conferences at the university where he teaches, and he’s become more involved in the academic world. Our relationship is more professional, not playful like it was.

Early the following year, then director of the Australian Centre for Photography Alasdair Foster included William’s three portraits of me in his curated exhibition Complicity. In the catalogue essay, William is quoted as saying: ‘I’ve come [to] realise that my photographs are all about a kind of complicity.’

I was quite chuffed to be William’s subject in a photographic show that included some of my heroes: Nan Goldin, Carol Jerrems and Larry Clark. Thinking about it now, this landmark 2000 exhibition was a natural precursor to ‘Up Close: Carol Jerrems with Larry Clark, Nan Goldin and William Yang’, curated by Natalie King at Heide Museum of Modern Art a decade later.

William and I don’t hang out anymore as we had during 1999, though we run into each other from time to time at art openings. I think he assumed that I had disowned these images, our shared history. Sure, his portraits and their texts made me uncomfortable. Not simply because I was naked. In hindsight, it was as William puts it, the playing out of an awkward intersection of art and life that had unsettled me. What is most compelling about his portraiture practice when it is focused on masculinity and desire is the way he forges a complicit partnership less in wrongdoing than in what seemed right at the time.

Last year I found William’s Outrage magazine spread in my archive and all these memories came flooding back. I always preferred this version of this photo rather than his re-shoot with the cringe-worthy blond hair. I scanned the image, posted it on Facebook and tagged William. He commented: ‘Glad you’ve resurrected this image, Daniel, rather than dismissing it as a folly of your youth’.

My Facebook reply: ‘William, I’ve always been proud of this image.’

William Yang, Daniel and Me #3, 1999

William Yang, Daniel and Me #3, 1999Courtesy of the artist

- William Yang, Friends of Dorothy, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1997, p.3.

- Russell Storer, ‘William Yang: Diary of a denizen’, in Natalie King (ed.), Up Close: Carol Jerrems with Larry Clark, Nan Goldin and William Yang, exhibition catalogue, Heide Museum of Modern Art/Schwartz City, Melbourne, 2010, p. 224.

- Daniel Mudie Cunningham and Emma Crimmings, ‘Mardi Gras ’97: William Yang & Nan Goldin’, Photofile, No. 51, August 1997, pp. 48–9; ‘Family ties’, Sydney Star Observer, 14 October 1999, p.13; ‘Sadness’, IF Magazine, no. 19, November 1999, p. 40.

- William Yang, ‘The younger photographer photographs the older photographer’, Outrage, no. 189, February 1999, p. 18.

- Alasdair Foster, ‘Posing truths’, Complicity, exhibition catalogue, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, 2000, p. 9.

- ibid., p.10.

Essay for Photofile.

Published by Photofile, issue 93 in 2013.