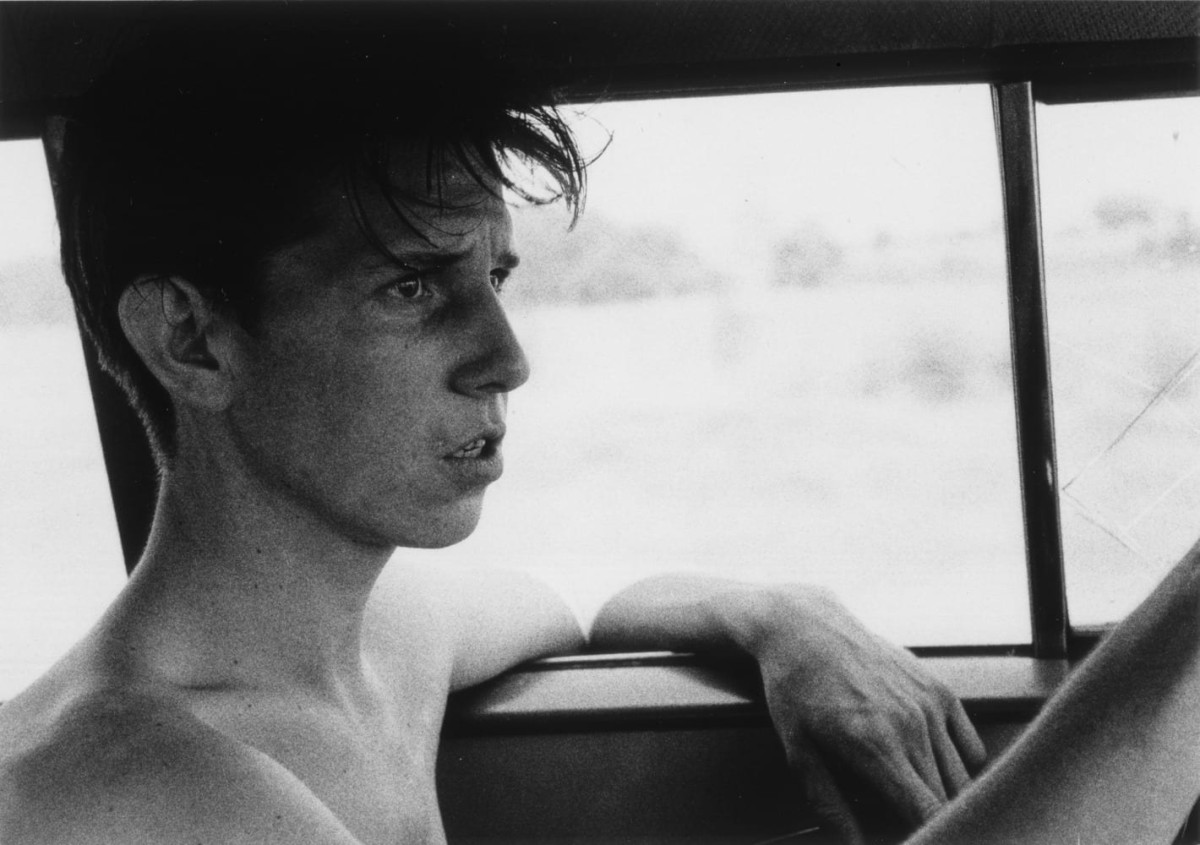

Larry Clark, Ken Park, 2002

Larry Clark, Ken Park, 2002The American Dream is commonly understood to mean the widespread aspiration of Americans to live better than their parents did. I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion that the American Dream has never been a widespread ideal because it is really a privileged white concept. The existence in America of a very visible white trash culture shows a breaking down of the American Dream (or Nightmare, for some). White trash is whiteness made visible due to poverty and hardship. When something white is marked or rendered visible by its trashness, it becomes white trash. As a cultural category, white trash disrupts the neutrality, dominance and privilege implied by whiteness through class.

The American Dream should hereafter be qualified as the Dream to be a Privileged White American. When we identify the whiteness of the American Dream, and the constant struggle for whites to rise above white trash, we can see that it is always already a failed project because once whiteness calls attention to itself it is inevitably trashed, regardless of its socio-economic specificity. As Richard Dyer writes, whiteness “secures its dominance by seeming to be nothing in particular” (1). If whiteness is nothingness, it exists as a law unto itself. Pursuing the White American Dream will always draw attention to whiteness, thereby undermining its naturalised dominance. No matter how hard whiteness tries to maintain its privilege, it always trashes its own internalised logic, rendering itself a form of white trash.

Right from the beginning of his career, Larry Clark has obsessively documented the failed American Dream and the impact of this failure on contemporary American youth who, with a few exceptions, are white. Clark has made five feature films: Kids (1995), Another Day in Paradise (1998), Bully (2001), Teenage Caveman (2001), and Ken Park (co-directed with Edward Lachman, 2002). None of them deal exclusively with a milieu of either privileged whiteness or white trash, but their interdependent depictions of race, class and sexuality call attention to the way these categories come to be produced in contemporary US cinema and popular culture. Lately, the focus on Clark’s work is mostly concerned with his depictions of sexuality. This is partly due to the controversial banning of Ken Park in Australia (2). According to some, Clark’s voyeuristic style exploits his subject matter on a sexual level, while for others, his ability to capture an authentic depiction of teenage sexuality is a rare thing in American cinema.

This essay will focus instead on the way he continually documents the failings of the so-called American Dream for its predominately white teenage characters. I will begin by briefly alluding to his early photographic work to foreground the issues of class, race and sexuality emergent in Kids, Bully and Ken Park.

Larry Clark, Billy Mann from Tulsa, 1963

Larry Clark, Billy Mann from Tulsa, 1963Dirty Glamour: Tulsa

Before making feature films, Clark first rose to prominence as a still photographer. His first photographic book Tulsa was published in 1971, and its autobiographical documentation of being a ‘high’ low life in his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma was acclaimed as a landmark achievement. Shot between 1963 and 1971, Clark’s black and white documentary-like photographs depicted the dirty glamour of speed-freaks and petty criminals with an alarming immediacy. Art critic Adele Hann describes Tulsa best when she says that these photos

were among the first to define the breakdown of the postwar American Dream, manifested initially by writers such as William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, the emergence of the Hell’s Angels style of outlaw tribalism and the phenomenon of Juvenile delinquency’. Like the work of Diane Arbus, which appeared at about the same time, Clark’s photographs seemed to depict a repulsive, tragic and hopeless seam in American life, a contaminating and disturbing vision threatening mainstream sensibilities and ambitions (3).

The “postwar American dream” to which Hann refers is really a white ideal. Certainly, all her references are white: Burroughs, Kerouac, Arbus. Clark’s early work as a photographer hit a cultural nerve because it unflinchingly depicted a dirty white trash landscape with the matter-of-factness that comes when one is so deeply involved in the scene (as Clark indeed was). The influence of Tulsa on other artists and filmmakers is evidenced by Nan Goldin, whose work followed Clark’s lead in the 1980s with similarly abrasive photographs of the American Dream being likened to a druginduced hallucination. Gus Van Sant also claims that his film Drugstore Cowboy (1989) was partly inspired by Tulsa.

A star was born in popular culture: its name was “heroin chic” and its aesthetic cohorts were, among others, Clark, Goldin and Van Sant. Ultimately, heroin chic was co-opted in the mainstream by Calvin Klein’s designer-slim advertising campaigns of the mid 1990s – even Fiona Apple’s video for her hit, Criminal mined the aesthetic – urging Bill Clinton to publicly criticise the glamorisation of heroin (4). Just in time for the global fashioning of heroin chic was Clark’s first feature film Kids. If Calvin Klein’s idea of heroin chic meant inducing catatonia on the catwalk, then Clark’s Kids provided a more authentic flipside to the tragic glamour. These kids smoked pot, not heroin, but they sure look like they could have appeared in Steven Meisel’s infamous photo-shoots for Calvin Klein.

Larry Clark, Kids, 1995

Larry Clark, Kids, 1995Unfriendly Ghosts: Kids

While Drugstore Cowboy was poetic in its depiction of drug-fuelled youthful abandon, (5) Kids was startling for its aggressive voyeurism and documentary styled ‘honesty’. The grainy textures, hand-held camera and use of non-professional actors imbues the film with an unsettling authenticity, even though it was entirely scripted and entirely designed. Co-producer Christine Vachon notes that despite the illusion of documentary authenticity, “it was scheduled, it was scripted, it was location managed, and it was production designed” (6).

If the film is as constructed as Vachon claims, we can assume that Clark’s intrusively voyeuristic view of these kids is also carefully stage-managed to ensure a ‘truthful’ and ‘authentic’ portrayal. As Clark declared in an interview, “Sometimes you have to cut

through the bullshit and tell the truth” (7). The film’s authenticity is often attributed to Harmony Karine’s script simply because he was 19 at the time and was part of the skater world so vividly detailed. Being so obsessed with truth value, Kids reads as a cautionary morality tale of how kids interact sexually in the age of AIDS. Moreover, the film presents teenage disaffection and recklessness as the by-product of an environment where the adults generally leave them alone. The parents pursue an empty American Dream, while the kids gravitate around its grim flipside.

The three main characters of Kids are white teenagers of varying socio-economic backgrounds whose lives are documented within a 24-hour period in New York City. Their larger group of reckless urban friends reveal a more diverse multicultural mix. Adults are rarely present; in the rare instance they are seen on screen, they appear disconnected and unable to fully relate to the kids. Neglect doesn’t seem to be the problem, as much as a general lack of time. In contrast, the kids have all the time in the world to indulge their every whim.

One of the main characters, Casper (Justin Pierce) is a self-proclaimed “horny ghost”. According to Karine, Casper was named after listening to Daniel Johnston, a songwriter who had written over 40 songs about Casper the Friendly Ghost (8). Casper is appropriately named because he is a spectral trace to the more charismatic Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick). Like the Friendly Ghost, the Casper in Kids is a blob of seemingly nonthreatening adolescent whiteness. If a childhood dress-up ghost is a white sheet covering the body, Casper earned his name because getting into the sheets is all he ever thinks about. Casper’s horniness especially increases when listening to Telly’s frequent and excitable descriptions of sex with “young baby girls”. When Casper’s not watching Telly, he’s listening to the self-proclaimed “virgin surgeon” rap about how fucking virgins is safe sex because they have “no diseases, no loose-as-a-goose pussy, no skank. No nothin’. Just pure pleasure”.

What Telly doesn’t know is that he’s the one with the “disease”. Telly’s one-time conquest Jennie (Chloe Sevigny) tests positive to the HIV virus after only one sexual encounter. Jennie spends the rest of the film looking for Telly to prevent him from sacrificing other teen virgins to his risk-heavy concept of “pure pleasure”. When Jennie finds Telly, he’s already in bed with another virgin, Darcy (Yakira Peguero). Jennie’s so stoned by this time that she passes out, joining the many inert teenage bodies strewn around the apartment. The next morning Casper finds Jennie asleep, decides he wants some of what Telly once had and rapes her.

According to film critics Jesse Engdahl and Jim Hosney, Casper’s “desire is fuelled by the fact that his best friend has just had sex with another virgin; having sex with Jennie is as close as he can come to having sex with Telly”(9). Similarly, Sean Desilets asks:

How far is it to the conclusion that, as Telly fucks Darcy, and Casper fucks Jennie, Telly fucks Casper, that the two of them are actualizing, through the bodies of these women, their libidinal attachment without the undignified necessity of actually admitting their own penetrability? Not very far at all, especially given the formative value of homoerotic desire in the kind of self-purifying masculinity that Casper and Telly produce together (10).

Women’s bodies act like a sexual bridge between Telly and Casper, rendering their relationship somewhat homoerotic, or homosocial at best. To disavow this homoeroticism, both characters reveal a distinct homophobia in their actions towards others. In one scene, an interracial gay couple pass by providing an opportunity for them to vent abusive taunts. Moments later Casper picks a fight with a black teenager because he had accidentally bumped into him. The black kid is beaten to a pulp, prompting cultural critic bell hooks to interpret this scene as “another opportunity for the teenagers to register white supremacist patriarchal cool” (11). If this bashing emphasises, for hooks, the inherent racism in dominant whiteness, it is also for Desilets, “a response to the anxiety invoked by the gay men [that] lays bear Casper and Telly’s homophobia” (12).

Whiteness comes to expose itself as an anxious state of affairs; anxious in the way it must be forever affirmed through racist means. The racism in Kids merges with homophobia and sexism because often their taunts reveal so much about their general attitudes to difference. Race, gender and sexuality are interlinked and ultimately express, as hooks notes, a “white supremacist patriarchal cool”. Their behaviour therefore speaks volumes about the way whiteness enforces its privilege through the systematic oppression of the Other. And the Other to dominant whiteness, as shown in Kids, is not simply blackness, but rather any identity category lying outside their limited frame of reference.

As Kids is about a community of teenagers whose parents are mostly absent, it is difficult to gauge exactly how these kids will pursue or trash the White American Dream. Their everyday lives are framed by the here and now, and not bound to the reality of labour, or an abstract concept of the future. Clark’s third feature Bully presents a similar dynamic within its teenage clique, except here the parents are so obsessed with their own White American Dream that it bears little relation to the twisted and misguided aspirations revealed by their kids.

Larry Clark, Bully, 2001

Larry Clark, Bully, 2001Kill Thine Enemy: Bully

Set in suburban Florida, Clark’s third feature presents an upper middle-class milieu where the adults spend the bulk of their lives earning a slice of American pie. The fruits of their labour are picket fences, sporty cars, and pretty children who wear bitchin’ clothes and (unbeknownst to them) take lots of drugs. Beneath the surface of this palm-studded paradise is a disaffection that is gobbling the children whole. Unlike their parents, these teens do not dream the White American Dream; instead, they’d rather retire after high school and join the slacker brigade. One of their parents says: “You guys don’t work; you don’t go to school; you don’t do anything. All you do is lay around and drive your cars and eat us out of house and home. Do you know how that makes me feel?” The dismissive response from one of the stoned minor characters is, “Mad?”

Based on true crime characters of the recent past, Bully’s key teens are Marty (Brad Renfro) and Bobby (Nick Stahl). They both have a part time job making sandwiches at a local deli, so their retirement has not yet happened. Their friends are similarly listless. Marty’s girlfriend Lisa (Rachel Miner), Ally (Bijou Phillips), Heather (Kelli Garner), Donny (Michael Pitt) and Lisa’s cousin Derek (Daniel Franzese) are the ultimate slackers who have nothing better to do than watch TV, have sex, do drugs, play video games, surf, and hang out. Bored with life before it has even really begun, the teens in Bully have it all but want none of it. When Lisa insistently proposes that they should kill Bobby, a combination of ennui and stupidity blinds the group into thinking her plan is a great idea. Thus, another aspect of the American Dream is laid bare: kill thine enemy.

Parents exist on the periphery in Bully, and one gets the impression that they genuinely want their offspring to share in their White American Dream. But whiteness and wealth doesn’t offer anything in the way of savvy street style. What does make for great fashion sense, however, is the appropriation of blackness within a community in which black people are strangely absent. Their whiteness is made more apparent through their highly gestural obsession with black culture. Except for Eminem, Bully’s soundtrack is mostly comprised of black hip hop and ‘gangsta rap’. In one scene Marty and Lisa watch an Eminem music video and Marty raps along to it, mimicking Eminem’s mimicry of black gangsta rap. Later in the film, an Eminem poster is seen conspicuously hanging from a bedroom wall.

Even though Eminem is often noted for his performance of blackness, these teens identify with Eminem’s white trashness. Eminem is evidence of the American Dream gone wrong due to the rising up of a white trash aesthetic. According to Gael Sweeney, the white trash aesthetic is the ultimate postmodern aesthetic because “decentering and fragmentation is reflected in the White Trash Aesthetic’s fixation with bits and pieces, with ... trivia, with display and decoration of the surface over contemplation of the interior, and on reproduction and speed over singularity and permanence, consumerism over art” 13). Even though Eminem’s musical identity is made up of multiple, fragmented personas like Slim Shady, Marshall Mathers and his stage name Eminem, the one recurring trait that binds them is the relationship they all share to the trailer park. Even Eminem’s semi-autobiographical screen debut, 8 Mile (Curtis Hanson, 2002) is about a young white rapper who dreams of transcending his poor white trailer park origins. Eminem’s music demonstrates how white trashness is not always about one’s own family background but is also about the appropriation and performance of multiple cultural references.

In Bully, the adoption of white-styled blackness derives from their identification with cultural icons like Eminem and finds expression in their fashion sense, the way they speak, and the way their bodies move. The music and media images of blackness to which they subscribe offer highly stylised gestures of rebellion, attitude, street cred. When white kids speak, dress and display themselves in a manner derived from black American culture, their whiteness becomes a rather awkward spectacle. For these teenagers, whiteness is boringly neutral and has no content of its own worth expressing. One reason whiteness has no visible content is because it has prevailed unchecked as a category of unmarked, unseen power.

The absence of real black people allows these slackers room to think identifying with black cultural signifiers is the ultimate in cool. Their appropriation of blackness and identification with Eminem’s white trashness highlights the discontent brought on by their privileged, dominant whiteness. The privilege bestowed on them by their inherited American Dream is so dull they’d rather adopt a trash identity, however stylised. The only authentic white trash character in Bully is the hitman (Leo Fitzpatrick) they enlist to help murder Bobby. Cinema almost always aligns real white trash with crime. These privileged white kids never see the criminality of their proposed actions until they have actually committed the crime. Killing Bobby is simply a solution to one of life’s many problems.

Larry Clark, Ken Park, 2002

Larry Clark, Ken Park, 2002Watching Springer: Ken Park

Life also abounds with problems in Ken Park. In the first scene of the film, we meet the titular character at the end of his brief life: Ken Park (Adam Chubbuck) is a young skater who films himself committing suicide. This sets the tone of alienation and disaffection experienced by its teenage characters. Peaches {Tiffany Lamos) suffers her father’s tenacity for violence and retribution after being caught having sex with her boyfriend; Tate (James Ransome) is a violent nutcase who resents living with his grandparents; Shawn (James Bullard) has secret sexual encounters with his girlfriend’s mother; and Claude (Stephen Jasso) is hatefully dubbed a “faggot” by his father because he’s “sensitive”. Later we see Claude’s father (Wade Williams) drunk and attempting to fellate Claude while asleep. This particular sub-plot explicitly reveals the way Ken Park is about parents who after failing to realise the American Dream try and ensure their kids similarly fail.

The fact that incestuous desires come to the fore is very much in keeping with the stereotype that white trash are often inbred and in bed with family members. Clark wants us to believe that Claude’s family are the most visible fuckups primarily because they are white trash. These adults failed to make real the White American Dream and as a result are white trash cliche: Mum {Amanda Plummer) smokes and drinks beer while pregnant; Dad is a violent drunk who abuses his son and tries to pick up prostitutes; Mum and Dad watch The Jerry Springer Show without actually seeing its humour. Is this because they are no different to those who appear on the show? They certainly exhibit some of the same cartoonish qualities we expect of white trash media portrayals, except there’s very little an audience can laugh at in this bleak world.

The teenagers depicted in Clark’s films never live ‘better’ lives than their parents, even though this constitutes a general understanding of the American Dream. Instead, they would rather just reject the imperatives thrust on them by their failed parents and live their lives in a manner that ignores the risks and heartache generally attending teenage sex, drug use, recklessness and rebellion. Clark shows how the space between adolescence and adulthood is a void contaminated beyond repair. The refusal to offer simplistic answers to the social problems associated with teenage life is a prevailing feature in Clark’s teenage universe. And the biggest problem of all is the way the White American Dream (or the Dream to be a Privileged White American) appears to be responsible for most of the damage.

- Richard Dyer, “White”, Screen Vol 29, No 4, 1988, p. 44.

- On June 17, 2003, a Censorship Forum was organised by Watch on Censorship and the Film Critics Circle of Australia to debate Ken Park’s banning in Australia.

- Adele Hann, “Living Out the Abject/Subject”, Art/ink, Vol 19, No 3, 1999, p.53.

- For a scholarly discussion that links Kids and Calvin Klein see: Henry A. Giroux,“Teenage Sexuality, Body Politics, and the Pedagogy of Display”, Review of Education/Pedagogy/Cultural Studies, Vol 18, No 3, 1996, pp. 307-331. For a critical discussion of heroin chic and images of thinness in advertising see: Rebecca Arnold, “Heroin Chic”, Fashion Theory, Vol 3, No 3, September 1999, pp.279-296; Katharine Wallerstein, “Thinness and Other Refusals in Contemporary Fashion Advertisements”, Fashion Theory, Vol 2, No 2, June 1998, pp. 129-150.

- Gus Van Sant repaid the debt of inspiration Drugstore Cowboy owed Clark by being Executive Producer on Kids.

- Christine Vachon with David Edelstein, Shooting to Kill: How an Independent Producer Blasts Through the Barriers to Make Movies That Matter, New York, Spike Books, 1998. p. 178.

- Cited in bell hooks, “Kids: Transgressive Subject Matter - Reactionary Film”, Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies, New York, Routledge, 1996, p. 61.

- Amy Taubin, “Skating the Edge”, The Village Voice, July 25, 1995, p.33.

- Jesse Engdahl and Jim Hosney, Review of Kids, Film Quarterly, Vol 1, No 2, Winter 1995-96, p. 42.

- Sean Desilets, “A Jennie Too Many: Narrative, Gender, and AIDS in Kids”, To the Quick, May 1999.

- bell hooks, ibid. p. 63.

- Sean Desilets, ibid.

- Gael Sweeney, “The Trashing of White Trash: Natural Born Killers and the Appropriation of the White Trash Aesthetic”, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Vol 18, No 2, 2001, p. 145.

Essay for Film Journal, a now defunct online magazine of film criticism and scholarship.

Published by Film Journal, issue 8 in 2004.