Rose Troche, Go Fish, 1994

Rose Troche, Go Fish, 1994By 1997, the year The Bent Lens was first published, queer cinema found itself at somewhat of a crossroads, staring into an uncertain future. Queer cinema was fast being absorbed into the mainstream, something that was certainly troubling considering 'queer' was a term injected with a range of meanings that included just about anything except mainstream, or normative, logic. The six or seven years preceding 1997 were identified, especially in the United States, as a time when queer film was electric, pulsing with the discordant rhythms of a period that came to be known—first by critics, second by audiences and lastly (if ever) by its practitioners—as New Queer Cinema.

In brief, the moniker New Queer Cinema was coined by film critic B. Ruby Rich to identify and categorise the larger-than-usual number of independent queer films lap-dancing around the US film festival circuit during 1991-92. Rich was referring primarily to the 'flock of films that were doing something new, renegotiating subjectivities, annexing whole genres, revising histories in their image'.

One of the problems for some critics, audiences and filmmakers was the fact that this growing wave of films were located in the boy-zone, where the splintering subjectivities of gay men dominated. Lesbian content was ensured, however, by filmmakers like Sadie Benning, Barbara Hammer, Ana Kokkinos, Pratibha Parmar and Monika Treut. But it wasn't until Rose Troche's Go Fish made a splash in 1994, that audiences everywhere recognised lesbian content in queer film had been sadly lacking. The success of Go Fish and others like it allowed viewers to whet their appetites (and perhaps even wet their legs) on lesbian narrative film.

Like many groundbreaking cultural forms, New Queer Cinema eventually became commercially viable. In the latter part of the 1990s, numerous New Queer filmmakers had abandoned strict queer criteria or simply opted for a more mainstream market. In 2000, Rich published another essay on the topic, this time reminiscing on the way New Queer had grown up and in many cases traded its independent origins for the mainstream. Rich argues that 'the story is more complicated than that, its conclusions less clear-cut, the movement itself in question, if not in total meltdown'.

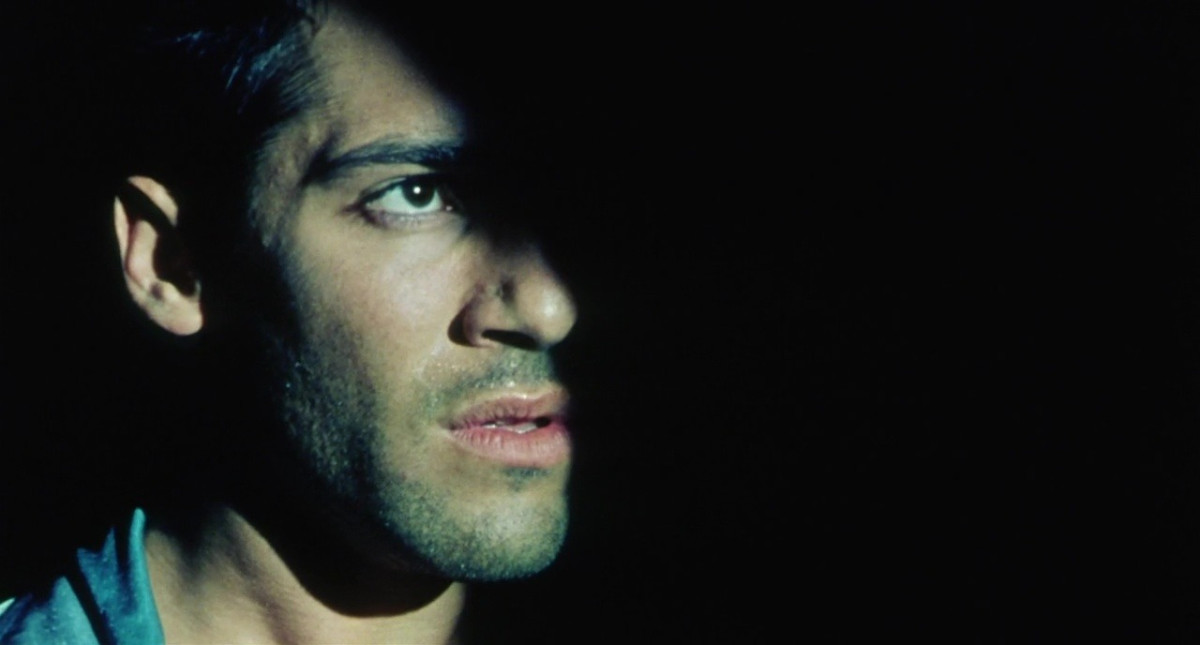

Todd Haynes, Poison, 1991

Todd Haynes, Poison, 1991For some, queer cinema may have sold out, become co-opted in the process of being pushed towards commercialisation. For others, it is this commercialisation that finally makes queer film digestible and less obsessed with avant-garde attempts to trash the rules of both identity and cinematic form. As an avid consumer of all things queer, I have found it difficult to decide a position to which I should subscribe. Surely if l elect the first, I am living in a fantasy world that expects Rose Troche to preside over the lesbian go-fishbowl, Todd Haynes to make Poison 2 and Gregg Araki to get over his Larry Clark-like obsession with disaffected post-adolescent flesh. If l subscribe to the second position, I have to admit I enjoyed (and sometimes prefer) relatively mainstream fare like Boys Don't Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999), The Broken Hearts Club (Greg Berlanti, 2000), The Opposite of Sex (Don Roos, 1998), Psycho Beach Party (Robert Lee King, 2000), as well as those I'm not likely to admit in print.

I must note, however, that an increasing number of commercial queer films do try and have it both ways. A recurring joke in All Over the Guy (Julie Davis, 2001) is at the expense of In & Out (Frank Oz, 1997), seemingly because any self-respecting queer who enjoyed In & Out has failed to see it as nothing more than a Hollywood exercise in safe-guarding thinly veiled homophobic sentiments. In & Out was hardly a great film, but it wasn't that bad. At least the sight of Kevin Kline and Tom Selleck locked in an oral embrace was worth the price of a weekly video hire. In contrast, All Over the Guy could have been granted a scholarship to the Nora Ephron Academy of Het-Rom-Comedy had the queer couples been cast by the likes of Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. But for something that better presents a brooding, contemplative idea of queer, I'd recommend we ditch the bitch fight sparked by All Over the Guy and rent instead the similarly titled All Over Me (Alex Sichel, 1997), a gritty teenage tale of sex, drugs and rock and roll set in Hells Kitchen, NYC, and starring Alison Folland.

This depiction of sex, drugs and rock and roll is not an isolated one. Such themes in queer cinema can be located when we connect some of the dots on Christine Vachon's resume as producer. Though Vachon openly dismisses being concerned only with queer product, she has produced a healthy dose of the more interesting queer films to come out of the United States. Vachon's post-1997 projects include the glam rock odysseys The Velvet Goldmine (Todd Haynes, 1998) and Hedwig and the Angry Inch (John Cameron Mitchell, 2001): proof that queers and disco aren't always synonymous. Moreover, these two films to a large extent re-write popular histories and myths through a queer framework; the former through music icons like David Bowie and Iggy Pop; the latter through its queer eurotrash take on Plato's Symposium.

This is not to say that the distinct independent sensibility of queer film has been totally abandoned. Surely the two glam examples cited above are still distinctive in terms of narrative, style and content. They may have the ability to reach a rapidly growing, potentially mainstream audience, but many viewers would agree that these films still inhabit the confines of the arthouse. Even Boys Don't Cry, which was also produced by Vachon, is something of an arthouse film, despite its well-known cast of nineties/noughties brat-packers, its critical and commercial success, and the Oscar and Golden Globe accolades bestowed on Hilary Swank for her transgender turn. This is a major accomplishment for queer cinema, but had the film not been based around Brandon Teena's tragic life, you have to ask whether it would have resonated on so many levels.

Lisa Cholodenko, High Art, 1998

Lisa Cholodenko, High Art, 1998Even though queer cinema has become a relatively commercial zone, much of it still derives from the context of independent filmmaking. It seems that indie films now have a decidedly commercial edge. Gems like High Art (Lisa Cholodenko, 1998) and Head On (Ana Kokkinos, 1998) demonstrate that independent films can happily exist outside of the Hollywood system, and still make an impact with audiences and in the market-place. High Art asks the powerful question: What do you find when investigating a leaky roof? Answers don't come easily, but when they do, you'll find Ally Sheedy, playing a has-been photographer who seduces 'the girl with the leak', while trying to stage a career comeback one minute and a drug run the next. Entertaining as the premise sounds, High Art is fiercely intelligent, darkly satirical, full of visual pleasure—clearly one of the best queer films of the last decade. The Australian film Head On finds raw poetry in its protagonist's fucked-up everyday. Identity, moreover, is not limited to queerness, because Head On is equally concerned with the attempt to locate one's sense of self within the nuclear family, and in relation to larger ethnic communities. High Art and Head On are successful examples of queer cinema primarily because their depictions of queer subjects and subjectivities is uncompromising. The simplistic demands for so-called 'positive' images of queer, lesbian and gay life has been replaced by beautifully flawed characters who resonate long after the final credits roll.

But the distinction between mainstream and independent (read Hollywood/non-Hollywood) has become increasingly blurred in recent times. Being John Malkovich (Spike Jonze, 1999) is a studio-financed, big budget piece that presents an unexpected and subversive lesbian happy ending for Catherine Keener and Cameron Diaz. On the one hand, this film is as commercial as it gets for queer. On the other, it goes beyond queer, and into territory that feels strangely new.

From American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1999) to American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000), much Hollywood cinema engages to varying degrees with queer themes, characters, subplots and subtexts. This doesn't mean such inclusiveness will always be embraced by queer audiences. Whether it be in Hollywood, the indie world or elsewhere, queerness only stands a chance of being interesting if it continues to revise and reinvent itself. The better films of New Queer Cinema or the more commercial recent past explode conventional modes of narrative and subject matter, all the while maintaining that the language of queer is always on the move, but also of the moment, from this moment on. By the time The Bent Lens is next revised, another moment will be upon us and up on the screen.

Ana Kokkinos, Head On, 1998

Ana Kokkinos, Head On, 1998- B. Ruby Rich. 'Homo Pomo: The New Queer Cinema' [September, 1992]. Reprinted in Cook and Dodd, eds. Women and Film: A Sight and Sound Reader. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993, p. 164.

- B. Ruby Rich. 'Queer and Present Danger' [2000] Reprinted in Hillier, ed. American Independent Cinema: A Sight and Sound Reader. London: British Film Institute, 2001, pp. 114-18.

Essay for the revised and expanded second edition of The Bent Lens, edited by Lisa Daniel Claire Jackson.

The Bent Lens also includes essays by Jack Halberstam, Barbara Hammer, and Helen Hok-Sze Leung.

Published by Allen & Unwin in 2003.