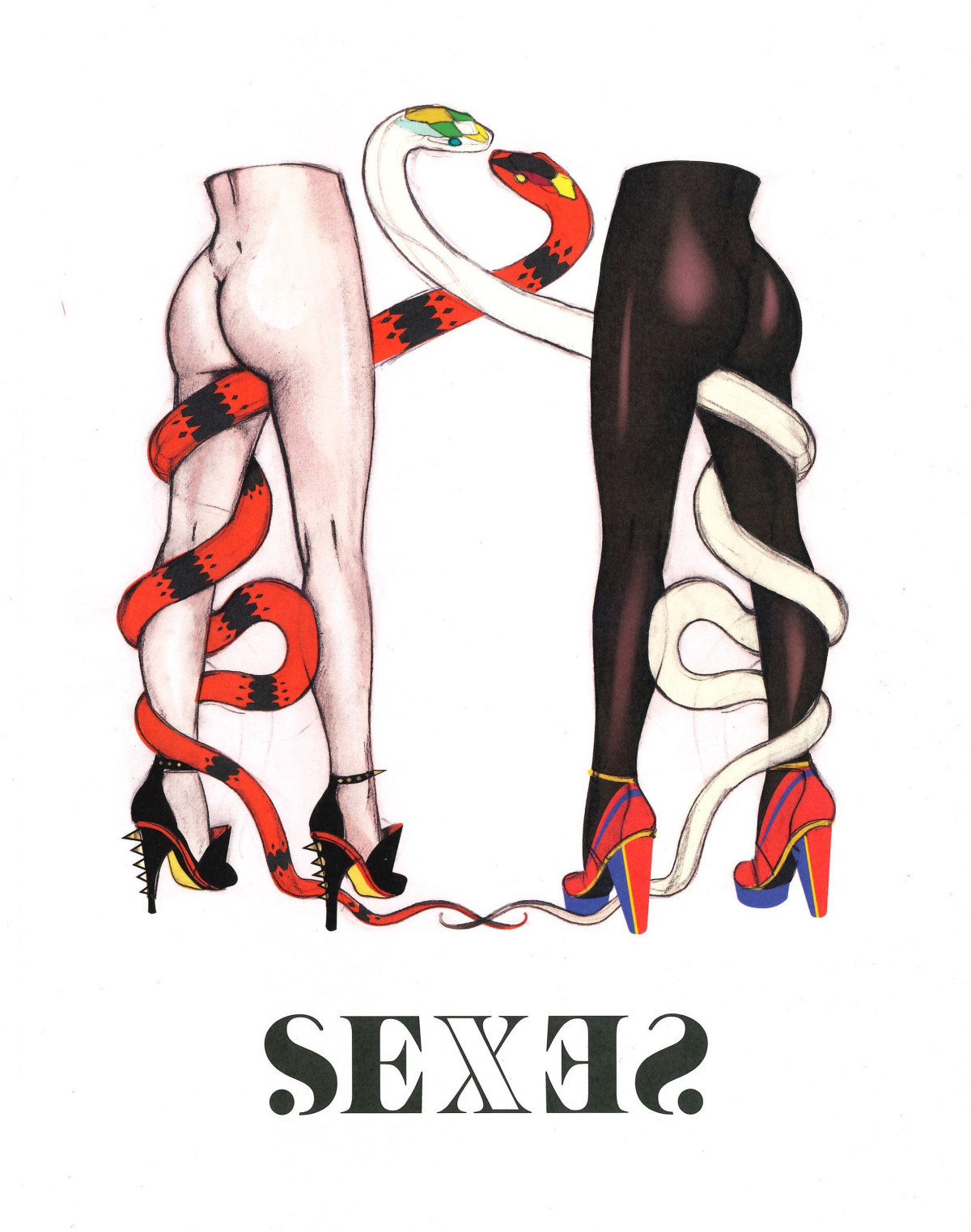

Exhibition catalogue cover for SEXES, 2012

Exhibition catalogue cover for SEXES, 2012Illustration: Técha Noble

Queer is dead in the ass.

Over the last two decades my work has frequently commented on aspects of queer visual, political and sexual culture. Fortuitously, my emergence in the contemporary Australian art world in the nineties coincided with the ascendancy of queer as a cultural category. Back then queer art exhibitions, performance and screen happenings were all the rage, and certainly in Sydney in least, Performance Space’s memorable programming at its former Cleveland Street dive-bar theatre-style location was its throbbing pulse.

Heated debate – a kind of bitchy lovers’ discourse, if you will – over whether it was productive to ghettoise yourself as a ‘queer artist’ was conducted over cask wine and stale cheese. In much the same way as artistic production founded on the faultlines of identity politics heeded the same ongoing convention-aspiring contentions, so-and-so would have exclaimed: ‘I don’t want to be curated into a queer show because I’m not a queer artist’. Similarly, artists like Tracey Moffatt and Gordon Bennett famously resisted being curated into exhibitions about Indigenous art. Who wants to be (or admit to being) an artist whose boxes could be ticked so easily? For queer artists in particular, this anxiety stemmed from a resistance to identity categories as concrete markers of who we were or what we did. Categorical identity terms and easy labels were rejected in a pursuit of infinite plurality and differentiation.

Paradoxically, a post-gay/post-lesbian generational demarcation of difference is what helped establish queer, regardless of whether the assertion of new sorts of labels was resisted. Queer then was mobilised as an identity category that refused categorisation as much as it resisted identity itself. It was a moment of possibility for those who embraced it, ushering in a wave of queer cultural production. Since the 1970s, a groundswell of Australian artists has made notable contributions to queer visual arts in Australia, including David McDiarmid, Peter Tully, Juan Davila, Luke Roberts, William Yang, Philip Juster, Scott Redford, Gary Carsley, Linda Dement, Aña Wojak, Christine Dean, Kurt Schranzer, r e a, Brook Andrew, Dani Marti, Trevor Fry, The Kingpins, Liam Benson, and Deborah Kelly, among many others. The annual Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras festival peaked throughout the 1990s, packed, as it was, full of dynamic queer art exhibitions, ranging from DIY grass roots or artist-run affairs to the institutionally supported.

Arguably the most significant queer exhibition of the era was curator Ted Gott’s Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS at the National Gallery of Australia in 1994. Thumbing through the book published to coincide with this show, it’s striking to note how many of the artists are now deceased, many others no longer practicing. This reminds us how many artists associated with this queer wave were significant for their marginality, but how it’s this very marginality that can ultimately continue to sideline them throughout their careers and beyond their time. This is the case especially for many important artists overlooked or left behind by the dominant canon of Australian art history, who have since been subject to archaeological maneuvers, now being actively restored or recuperated by curators and scholars (Sally Gray’s work on David McDiarmid; Robert Lake’s exhibitions on Philip Juster; Craig Judd’s work on Stuart Black; my own work on Arthur McIntyre; and hopefully more to come on artists such as Brenton Heath-Kerr and the like).

Thinking back on these times, it is evident how one of the great promises of queer was that it reinvented representational concepts of transgression, subversion, playfulness, and pleasure. At its transgressive best, queer glowed like radium, ready to contaminate a dominant culture that had originally invented the term as a homophobic slur. The power of queer was its promiscuously shifting goalposts, its ability to be everything and nothing at the same time, the manner in which its gravity was produced by its groundlessness. Being everything and nothing comes with its risks, though. Be careful what you wish for, my mother once said.

Queer aimed to be inclusive: straights were queer, queers were straight. The term was available to any individual or community that laid claim to an ethos of difference. At once everything and nothing, it was a convenient idea (a pillow for the marginalised) but also a strategic one (emphasising fluidity and change). Queer was post-gay, post-lesbian, surely easier to digest than the gluten-free sandwich press known as GLBTI: that ever-expanding acronym of sexual minorities.

Last time I surveyed the legacy of queer in an essay for Art & Australia (issue 46.4, 2009) I was hell-bent on retaining/ reclaiming/ rethinking a position for queer within the context of contemporary Australian art, as an act of remembering why it came into being in the first place: to oppose the selfsame heteronormativity that has crept into contemporary homosexual cultures, rendering them dull, vapid and commonplace. The process by which normalisation has become the great goal of dominant gay culture may be read as symptomatic of Australia’s more broadly entrenched political conservatism, and its attendant aspirationalist values. Lisa Duggan, writing in The Twilight of Equality: Neo-Liberalism, Cultural Politics and the Attack on Democracy (2003) argues: ‘new neoliberal sexual politics… might be termed the new homonormativity—it is a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of a semimobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption.’

Top down and bottomed out, the politics of queer once mattered because in them was a sense that change wasn’t simply being performance managed; it was being fist-fucked into existence. Gays once had a well-thumbed, Crisco-scented copy of Foucault’s The History of Sexuality Volume One in their back pocket; these days ‘the care of the self’ is funneled into privatised, narcissistic dross like Alan Downs’ The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man’s World. Foucault’s theory of the docile body being regulated and produced when social subjects submit to social norms happens nowhere more presciently than in a queer culture desperate to prove itself, formation dancing up Oxford Street for acceptance. To embrace fragmentation and chaos was once a productive strategy of dealing with simply being in the world, whereas these days it seems more symptomatic of a general state of being broken and in need of healing. Maintain the rage, velvet optional.

Of course there’s great rage maintained in the fight for rights to same-sex marriage; access to adoption, surrogacy and IVF; as well as the desire to worship whatever you want freely (including a God that considers you an abomination). Yet our relentless replication of heteronormativity packaged as a quest for equal rights makes queer unqueer. The uncritical reproduction of the oppressive structures that made us invisible for so long erases queer. In that erasure, our invisibility is assured within a rebranded set of norms that rubs us out in the process of being drawn into the very thing that once oppressed, and continues to oppress.

Queer theorist Jack Halberstam claims that ‘queer time’ was defined by the pervasive sense of loss felt by the AIDS crisis of the late twentieth-century: ‘And yet queer time, even as it emerges from the AIDS crisis, is not only about compression and annihilation; it is also about the potentiality of a life unscripted by the conventions of family, inheritance, and child rearing.’ [In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives, 2005] The allure of queer was its critical embrace of marginality and difference, its elusive resistance to definition and closure, the way it articulated the margins as a space for new representational dialogues and debates.

This is queer before it had its guts ripped out. Before the politics dropped out. Before the amnesia set in. Before marriage equality was all we had left to bang on about. Before a Facebook group called ‘Lost Gay Sydney’ was set up to remind a queer community of what it once was, however pointedly melancholic this memory lane trip turned out to be with its unremitting newsfeed parade of queers lost to AIDS and other tragedies.

At some point I realised I’d become a straight-acting queer. Not straight-acting as in performing as straight for the purposes of disguise, passing or sexual role-play. I mean the aspiration to a straight-acting heteronormativity. The writing of my queer life is punctuated with experiences where I’ve used queer against itself in some grand normalising negotiation of meaning, identity, whatever. Surely queer lends itself to great manipulation if it’s going to be so elusive in its own terms of reference. It’s this very manipulative impulse that can enact a veritable arcade of ideological play.

A banal case in point. A few years ago when Mardi Gras still described its annual festival, parade and party as ‘Gay and Lesbian’ (in November 2011, in the name of inclusivity, it dispensed with the terms) I was engaged pro-bono to consult on the visual arts content of the festival, and in exchange was paid in party tickets. When I received two tickets I explained I required three tickets because I had two boyfriends. I decided I could use my then attempt at ‘polyamory’ (such a detestable word, really, when ‘slut’ suits most gays fine) to manipulate the political correctness driving (the implicitly dyadic sexual identity politics of) an organisation like Mardi Gras. God forbid I let a community-led bureaucracy built on sexual liberty for queers discriminate against my then quest for non-normative, non-dyadic sex! In hindsight, the episode was amusing because I was given three tickets no-questions-asked by a staffer whose surprise at my matter-of-fact revelation was thinly disguised by an attempt to mimic my own nonchalance. My polyamory was a queer affront to convention and, therefore, logic permits that it must be rewarded with equal rights to complimentary party tickets. You’ve gotta fight for your right to party.

If queer wasn’t dead in the ass, what would it look like today? Having been born out of recuperating a once homophobic slur, surely it is possible to reclaim it again? Or would that be like flogging a dead whore? The problem with attempting to imagine what queer looks like today is that the margin has well and truly eroded. Where is the margin within marginalism? A byproduct of the infinite proliferation of endless micro counter publics in the digital sphere is the here-today gone-tomorrow roll call of communities that set themselves up as resistant to dominant communities. Digital media and the internet allow everyone to be connected and isolated at the same time, in an endless play of sameness and difference. Micro communities – fetishistic sexual subcultures for instance – emerge here and experience temporal liberation but in doing so become yet another link on a much larger food chain of digital signification. The internet becomes less the tool of great emancipation it purports to be and more just a remediated local sewing circle, where everyone’s catered for. Subculture today, meme tomorrow.

Where is the space to reclaim anything when there is an immediate Facebook group that gathers around when someone is marginalised? Click Like if you believe the transgender girl in Ohio should be allowed to take her girlfriend to the Prom. We are faced with a moment when the inside appropriates the outside as yet another category of itself. There is no outside to this system – no politics of resistance to this relentless form of consumer logic.

Against this background and at this cultural moment, what makes it possible to be queer? Who are the marginalised if not the serial killers, merchant bankers, and pedophiles amongst us – those one percenters left in the community that no one knows how to deal with. John Waters’ illustrates this best when he famously said: ‘The ultimate irony is that I'm becoming part of the establishment.’ We are the 99%.

Vale Queer.

Polemical catalogue essay for SEXES at Performance Space, Carriageworks, 26 October – 1 December 2012.

Published by Performance Space in 2012.