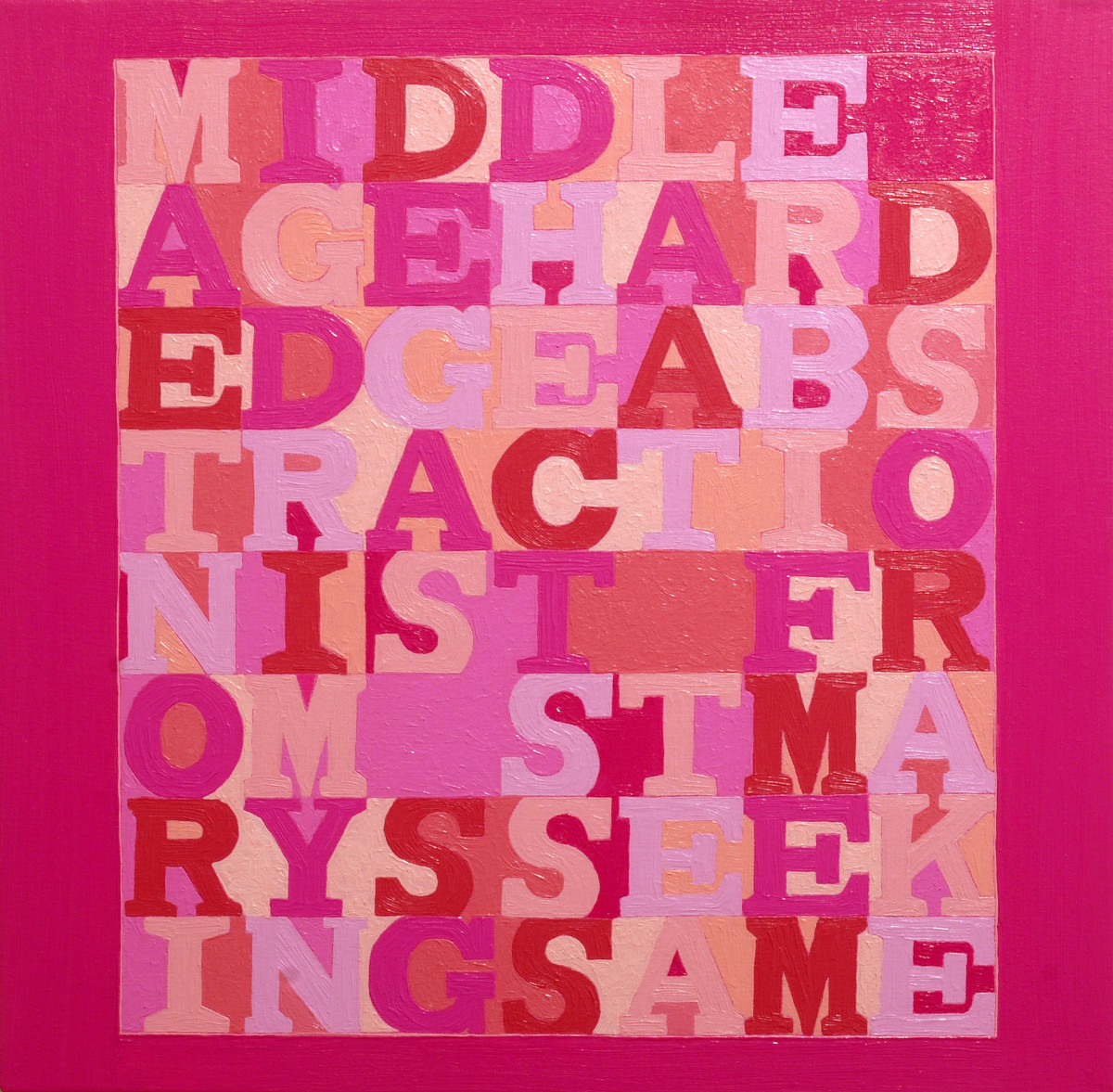

Christine Dean, Middle Age Hard Edge Abstractionist from St Marys Seeking Same, 2007

Christine Dean, Middle Age Hard Edge Abstractionist from St Marys Seeking Same, 2007The idea for Bent Western emerged from an essay by Christine Dean called Mollies of the West. Published in the catalogue for Western Front (Blacktown Arts Centre, 2005), Dean uses ‘molly’ as a descriptor for gay Western Sydney artists. Since the early 1990s, the term ‘queer’ has been used to refer to contemporary cultural expression by non-heterosexuals, so I found her use of an antiquated term like molly rather curious.

Was molly an old word for queer that could be recontextualised in a contemporary regional setting like western Sydney? According to Dean it could:

Mollies were often depicted as bawdy or licentious social satirists who often cocked a snoop at the establishment while remaining committed to the values of their working class origins. Significantly, many of the original mollies were transported to Australia as convicts and presumably some of them would have made their way to what is now Western Sydney.

The terms we use to describe ourselves and our cultural expressions are important, even if they elude fixed meaning. Whether we use ‘queer’ or ‘molly’ or any other term to describe who weare or what we do, ultimately you can be sure these names will always be contested. Bent Western settles on queer as the most convenient classification for the work surveyed even if it does not always provide the perfect fit. It seems that branding culture queer legitimises the margins, rendering queer vulnerable to cooptation once assimilated into more mainstream cultural forms.

Once queer is made visible through knowledge and discourse formation it is subjected to a conceptual erasure, rendering queer unqueer. This exhibition resists trouble-free answers as to what queer should mean in this specific time and place. The artists in Bent Western have lived, worked or studied in Western Sydney and made important contributions to queer cultures in the region and beyond. The ‘mollyism’ Dean describes harks back to fairly bent and illicit antiestablishment behaviour. Interestingly, many of the artists in Bent Western emerged from an establishment that no longer exists. The art school at the University of Western Sydney, which has been abolished in recent times, produced many important queer artists including ten artists in Bent Western who studied Fine Arts there.

My connection to UWS was as a student and, later, as a lecturer. I started curating shows independently in the mid 1990s with fellow art students from UWS, some of whom feature here [and later in Space YZ]. My first exhibition was Drag Races (1995) at the defunct artist-runinitiative Nepean Arthouse, which was located in a warehouse on Union Road, Penrith. This show meshed ideas of drag and race in work by queer Western Sydney artists and included Tim Hilton and Erna Lilje. I curated two queer exhibitions at Raw Nerve, which used to be housed in the Erskineville premises of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras: Show Pony (1997) looked at queer style and Home Sweet Homo (1998) examined queer domesticity. The latter included an installation by Erna Lilje that matched monochrome paintings with a customised gay porn video; it amuses me still that she edited the video at UWS despite staff trying to shut her down. A few years later I curated Flaming Muses (Performance Space, 2002) which looked at the collaborative process involved in the work of queer artist couples and featured José Da Silva and Ron Adams. In 2005 Liam Benson, George Tillianakis and Ron Adams appeared in Dress Code at MOP Projects (2005), a show critiquing the vapid marketing excesses of ‘metrosexuality’.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Gender is a Drag, 1993

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Gender is a Drag, 1993Performance at University of Western Sydney. Photo: Ross Cunningham

During the 1990s I dabbled with performance art and regularly appeared in cLUB bENT, a landmark series of queer cabaret events that occurred during Mardi Gras season at Performance Space (1995-7). For me, the most noteworthy of the performances from this time happened a few years earlier at the Allen Library window spaces at UWS, Kingswood campus, on 25 November, 1993. The performance was called Gender is a Drag and featured a video component depicting myself sitting in a chair, experiencing a gender transformation marked by make-up and hair-dye. While this looped, I performed the companion piece in the neighbouring window by cutting off my long hair in a butch gender reversal. A reference to Frida Kahlo’s painting Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) was made explicit when I wrote on the window in lipstick: “Look, if I used to love you, it was because of your hair; now that you’re shorn I don’t love you anymore”.

The process of curating a survey like Bent Western has prompted some self-surveying, as suggested above. The research undertaken is inevitably drawn from my own experience of living and working in Western Sydney since 1993 and being part of a community of lively queer artists, most of whom I have known for some time. Initially I conceived that Bent Western would follow on from Dean’s essay by examining art from the early 1990s until the present. But to my delight the survey was expanded to a three decade period, in keeping with 2008 marking the thirtieth anniversary of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. One of the most compelling aspects of Bent Western has been unearthing the work of Arthur McIntyre, who was born in Katoomba in 1945 and died five days before his 58th birthday in 2003.

Arthur McIntyre came to public attention for Survival Series (1975-78) and Survival and Decay Series (1976-79), two major bodies of collage works that combine medical and porn images. These images are just as powerful and unsettling today because by juxtaposing sex and disease, they preempt an AIDS crisis that was just about to erupt globally. In Contemporary Australian Collage and its Origins, McIntyre writes: “In retrospect, my series on sexually transmitted diseases was hideously prophetic in our age of AIDS. My intention was never to preach, nor moralise… I was simply intrigued that so much suffering can result from acts of love – and by notions related to pleasure, pain and death” (1990). McIntyre continued making bold mixed media works until his death in 2003, never exhausting a fascination with sexuality and the body. Art and Man (1986) is an example of his enduring interest in masculinity and media images, while Bad Blood and Investigation (both 1999) reflects his interest in true crime narratives.

Arthur McIntyre, Art and Man, 1986

Arthur McIntyre, Art and Man, 1986Collection: Macquarie University

Michael Butler also uses found porn imagery in his collage and mixed media works. Butler has featured in several Western Sydney exhibitions about queer politics because his practice consistently negotiates the relationship of gay sexuality to public space. Drawing heavily on personal experience and an interest in true crime, Butler creates seductive and off-kilter worlds where gay sexuality finds a means for expression despite its proximity to violence, trauma and pathologisation.

José Da Silva also borrows from porn to examine the link between trauma, gay subjectivity and the power relations that organise groupings of men. Untitled (Unter Männern) (2004) is a found internet image of naked soldiers showering in the Iraqi desert, its manipulation heightening homosociality through the obfuscation of identity. Da Silva inserts himself into the frame in the Nowhere series (2005-06) in sexual scenarios that interrogate the serial nature of facial affect.

Lionel Bawden has carved out a practice with trademark pencil sculptures that are organic in shape and elliptical in meaning. In the late 1990s, his work was more directly informed by gay aesthetics. C.V. (cock vitrine) (2007) remakes the early pencil sculpture objects of desire (1998) – its phallic shape a witty ‘pencil dick’ pun. The title C.V. juxtaposes the drive to notch up artworld success in one’s Curriculum Vitae with the ‘trophy’ mentality of conquest prevalent in gay culture. Bent Western also includes the comforts of anonymous paper men (1997), a mattress incorporating paintings of sex between men and based on images from magazines usually kept hidden under the bed.

Christine Dean puts to bed modernist mythmaking. Pink Bedspread (1996) uses a chenille bedspread as a canvas that mixes references to the masculine bravado of modernist monochrome painters with the arbitrary colour coding of gender. Using thickly applied enamel house paints, Dean underscores the normative processes that animate compulsory heterosexuality and its queer undoing in suburbia. Dean’s Middle Age Hard Edge Abstractionist from St Marys seeking same (2007) is one of four new fanciful tributes to Western Sydney histories.

Similarly, Western Sydney is frequent subject matter for Marius Jastkowiak. His solo exhibition at Blacktown Arts Centre, Maintaining an Equilibrium of the Fantastic (2007) showcased paintings of neon-lit nightscapes that subtly abstracted the fuzzy edges of suburbia. As its title suggests, Man Taking Shower in Granville (After David Hockney) (2006) is a rare moment where Jastkowiak represents homoeroticism through the blurred contours of the male nude rather than the sexually charged potential of being outside at night.

Kurt Schranzer fuses gay iconography with references from modernist art and literature. The painting Self-Portrait on Christmas Eve, Whilst Masturbating (1986) foretells his longstanding interest in melancholy eroticism. In contrast the yearning symbolism of The Sailors Kissed and Shot Stars (2004) shows the direction his work took in the last decade towards illustrative draftsmanship.

Ron Adams also uses the visual languages of modernism by borrowing from Russian Constructivism, De Stijl and the Bauhaus as the motivating imprimatur for pop culture sound bytes rendered in text. Earlier in his practice, Adams was a surrealist who merged organic and machine parts in perverse configurations as seen in the POD series (1998). Bent Western also includes the photographic collaboration with George Adams, Yellow Streak (2000), a deadpan homage to Gilbert and George.

Drew Bickford is an illustrator and sculptor whose work reflects an obsessive interest in horror, deformity and true crime. Bickford plays surrealist mind games by depicting how social and moral deformity manifests in physical ways. Bent Western includes the subtle sculptural piece Exist (2000) alongside more characteristically abject works like The Speckled Hen (2005).

Erna Lilje makes installations with objects divested of conventional scale and proportion. Lilje’s work since the early 1990s has probed the way museum conventions of display and presentation mediate reception. Locating spectatorial desire somewhere between seductive tactility and cool ironic detachment, Lilje creates hermetically sealed worlds that both lure and elude.

Karen Coull’s sculptural objects engage the politics of gender and sexuality through prickly puns. Soft Touch and What Fresh Hell is This (both 1994) challenge notions of passive and subjugated femininity by spiking the tools of domestic labour with thorns. Repulsive and alluring, Coull’s domestic implements convey anthropomorphic potential – quite possibly creatures of an unconscious realm.

Jessica Olivieri uses installation, video and performance to make whimsical artworks drawn from personal anecdotes. Amore for War Horses / Family Man (2006) is a performance video set to the eponymous Fleetwood Mac song. Three women including the artist perform a playfully choreographed dance routine costumed in oversized pom-poms. Formation dancing within a blue room, it is like an audition for a Degas painting held on the bottom of the sea.

Tim Hilton creates washed up drag characters fabulous for their anti-aesthetic anathema. The photo series Shadowside (2006) are digitally manipulated images of the artist pushing his drag personas into dark and primal realms. Bent Western also includes Exquisite Garden (1996), an early example of Hilton’s installation practice that transforms found neckties into phallic plantlife.

Liam Benson’s performance, photographic and video work celebrates how understandings of place contribute to the construction of gender stereotypes. His collaboration with Kenzee Patterson, Lock it or Lose it (2004) is a glamorised celebration of Western Sydney clichés, while Bleeding Glitter (2005) draws on advertising language to navigate the role of trauma in the formation of gay identity.

George Tillianakis is a performance, video and music artist who uses his body to unpick concepts of selfhood. Through the layering of persona, action and sound, Tillianakis shirks narrative conventions in favour of elliptical exploits thick with symbolism drawn from personal experience.

Anastasia Zaravinos is the youngest artist in Bent Western and a force to be reckoned with. Zaravinos makes confronting video and performance work that puts a contemporary queer spin on visceral feminist body art. Zaravinos tests corporeal limits, confounding normative gender codes through demented drag personas. Razor sharp and dark, her mix of pop satire and personal torment makes her an artist to watch.

Bent Western demonstrates how art about sexuality always evokes a sense of place. Western Sydney has offered a unique dimension to the queer experience, even if it is sometimes marginalised or disconnected from the visible pockets of queer cultural activity that proliferate in urban contexts. The knife edge of queer risks becoming blunt once assimilated into media mainstreams, but thankfully the suburbs are alive with artists leading the way in resisting the unqueering of queer. It is without a doubt that Western Sydney will continue to generate intrepid queer artists and we can be sure that bent perspectives will continue in this region no matter what.

Anastasia Zaravinos, Portrait of Christina Superstar, from Glamour TV, 2007

Anastasia Zaravinos, Portrait of Christina Superstar, from Glamour TV, 2007- Christine Dean, ‘Mollies of the West’. Western Front: Art is a Social Space. Blacktown, NSW: Blacktown Arts Centre, 2005.

- Arthur McIntyre, Contemporary Australian Collage and its Origins. Roseville, NSW: Craftsman House, 1990.

Curatorial catalogue essay for Bent Western at Blacktown Arts Centre, 8 February – 12 April 2008.

Published by Blacktown Arts Centre in 2008.