Fiona Kelly McGregor, Buried Not Dead, Giramondo, 2021

Fiona Kelly McGregor, Buried Not Dead, Giramondo, 2021Back in the early-to-mid 1990s when Fiona Kelly McGregor was an emerging young writer, I would see her around the queer Sydney scene. My lesbian housemate had acquired Fiona’s first novel. I read it after she did or more likely at the same time; it was a share-everything-share-house-scenario.

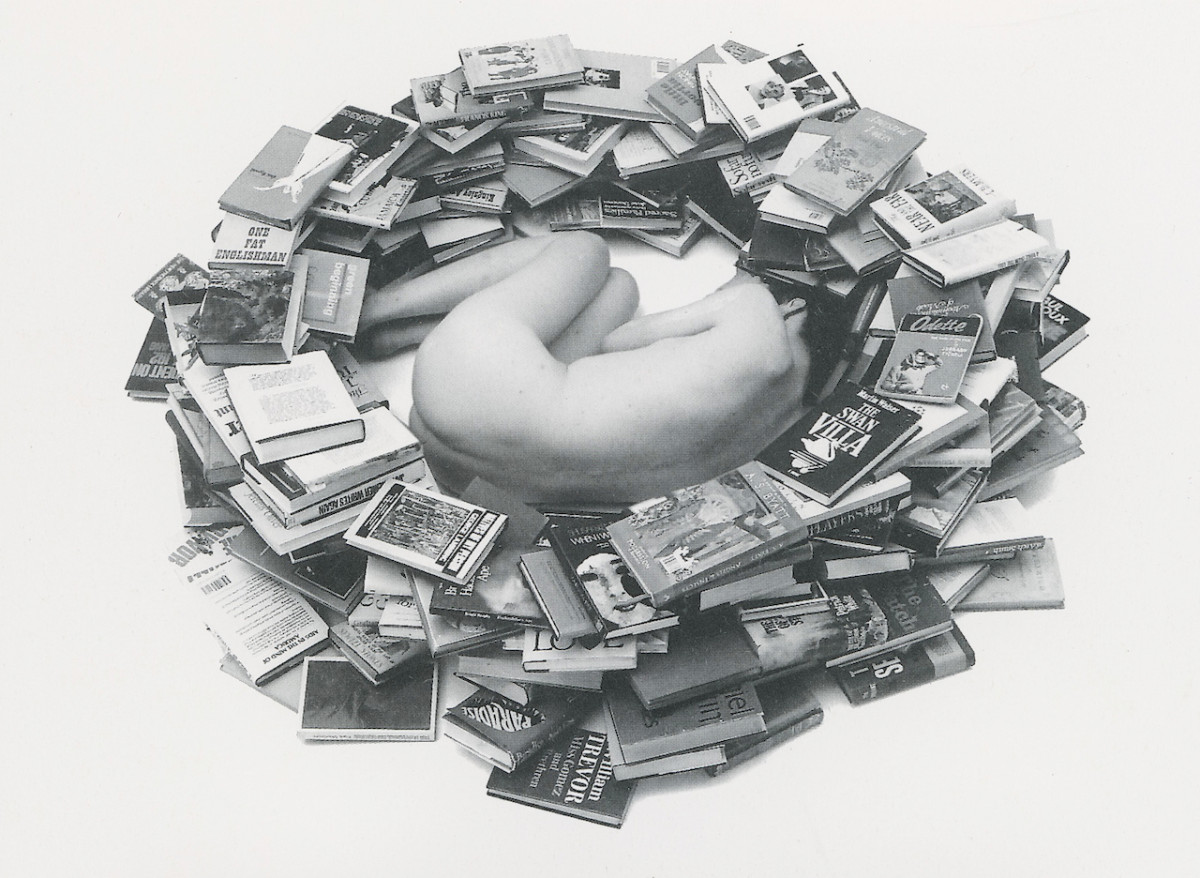

Around that time Fiona was photographed by William Yang for Blue magazine in 1995 (and later reproduced in his 1997 book Friends of Dorothy). The photo shows Fiona curled up in a foetal position on the floor, naked, cradled by an encroaching circular wall of books. It is a striking image, more artful and stylised than the usual documentary, candid or snapshot style for which William Yang is known.

I didn’t know Fiona then but saw her around the queer scene, and she always exuded a powerful aura. I was kind of intimidated by her. As she evolved into a performance artist over the next decade I’d see her around the art scene where I was becoming ensconced.

Eventually, we met in 2010. She had moved to Redfern by this stage, and was about to have an exhibition at MOP Projects, a former artist-run initiative nearby in Chippendale. We met at her house, where she told me about the new work for MOP as I had been engaged to write the catalogue text.

Before I left that day she gave me a signed copy of her 2008 book Strange Museums, which documents her performance art tour of Poland with collaborator and former partner AñA Wojak. Nobody else I knew of in Australia had written a memoir like it, especially one that blended performance art with the literary conventions of the travel memoir. I re-read Strange Museums recently. It holds up.

Returning to that William Yang photo all these years later as I write these notes for this book launch, I am struck by how the image encapsulates what Fiona has achieved with her new book of essays, Buried Not Dead. Quite literally she is buried not dead by the weight of words, piles of books, essays upon essays surrounding her.

William Yang, Portrait of Fiona Kelly McGregor for Blue magazine, 1995

William Yang, Portrait of Fiona Kelly McGregor for Blue magazine, 1995Courtesy of the artist

A line from David Bowie’s Conversation Piece echoes in my head as I look again at this photo:

And my essays lying scattered on the floor

Fulfill their needs just by being there…

A collection of essays on art, performance, literature, sexuality, politics and activism – Buried Not Dead is a work of cultural and social memory. Of a life lived through the pulse of the city and its vicissitudes.

What William Yang is to photography, Fiona Kelly McGregor is to literature. Without her astute eye, her having-been-there, these accounts, especially of queer life, would simply not exist.

By documenting the parties and queer cabaret culture of the recent past, she evokes Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Redfern and Eveleigh of old, before urban gentrification occurred and with it a certain gentrification of language.

As identity politics have evolved over time so has the terminology used to describe it. Her book opens with a disclaimer that the language and terms have been retained as written in their original form, regardless of their capacity to offend cancel-culture-cops. This is bold and fearless. In her most recent essay for this book, Where Your Cabaret Comes From, she describes a nineties genderfuck performance by Imogen Kelly, and in doing so realises the language we used then does not suffice now:

This was in the very early days of the transgender revolution, when we still said F2M, and some butch dykes habitually packed, let alone wore explicit male drag… We don’t even use the same terminology.

Later in the same piece, she reflects: We’d come of age in a coalitionist culture – what you’d call intersectional now…

Buried Not Dead is an urgent book. It not only documents a barometer of a time and place; it presents a measure of this author’s subjective experience and perception. Even though most of these essays have been previously published in anthologies, journals and art magazines; this collection is a reminder that these types of histories are susceptible to loss as print culture and the publishing industry around arts writing changes with fewer opportunities and platforms remaining. In her extraordinary essay on Latai Taumoepeau, Fiona observes that despite her acclaim as an artist, the reduction of arts coverage in Australia is possibly one such reasons that few have written about her work. It means Fiona’s text sets the benchmark for other writings bound to come on Taumoepeau’s work. We know that we are constantly fighting to protect our histories. For this reason alone, we rely on writers like Fiona Kelly McGregor to perform the communal and participatory act of bearing witness. Followed by the disciplined solitude of retreating to, what she calls in one essay, the writer’s cave.

Among these reworked essays are pieces originally published in RealTime and Sturgeon – the former, long running and the latter, short lived. Both no more. For six issues I edited Sturgeon and am forlorn it didn’t have a longer life. Some of my own best work bleeds into those pages, which sit now in the obscure corners of the internet – if you know where to look. It is a pleasure to see Fiona’s Sturgeon essay on Samoan artist Greg Semu rehabilitated for the current moment and contextualised alongside other writings on artists, writers, dancers, tattooists and DJs.

Among them, her essays on iconic performance artists Marina Abramović and Mike Parr are among some of the best I’ve read on these celebrated and widely written about figures. What sets Fiona’s words apart is that she writes art criticism like a novelist; she writes novels like a performance artist (her acclaimed previous opus, Indelible Ink is very much a testament to that).

Fiona’s read on Marina Abramović is embedded with ambivalence around the contradictions that Marina-the-celebrity now represents as her global fame and notoriety took her into the mainstream, making her a cult-like industry – a ‘Jesus Abramović’ – that commodifies any of the radical gestures that produced her in the first place. In reflecting on this Fiona realises her initial interest in Marina is precisely because she:

did with fine art what Sydney’s queer underground was producing every weekend: performance that dealt in limit experience; the personal ordeal highlighting political oppression; in the abject and absurd, the sublime and transcendent; freedom, above all; corporeal and social.

What makes Buried Not Dead so original is how art and life aren’t parallel lines.

Entwined within Fiona’s deep dives into the complexities of her subject’s practices – and their personas – are reflections on her own time as a performer, her own persona over time. This presents an elegant frame within which sits a memoir of Fiona Kelly McGregor-the-artist. And one that at times has its melancholies and vulnerabilities. She writes:

For fifteen years I made performance art, then five years ago retreated to my desk full of unanswered questions. I don’t know if I will ever make performance art again.

Fiona Kelly McGregor wrote those lines about five years ago. I think she was wrong. Her performance art practice thrives through her urgent words: her capacity to chronicle a scene for which she is such an intrinsic part. And in doing so, reflect on her own contributions to that world, knowing, indeed certain, that there is much more yet to be exhumed.

Fiona Kelly McGregor at the book launch for Buried Not Dead, 2021

Fiona Kelly McGregor at the book launch for Buried Not Dead, 2021Photo: Kate Prendergast

Unpublished speech notes for the book launch of Fiona Kelly McGregor's Buried Not Dead at The Townie in Newtown, hosted by Better Read Than Dead and organised by publisher Giramondo, 25 March 2021.

Published by danmudcun.com in 2021.