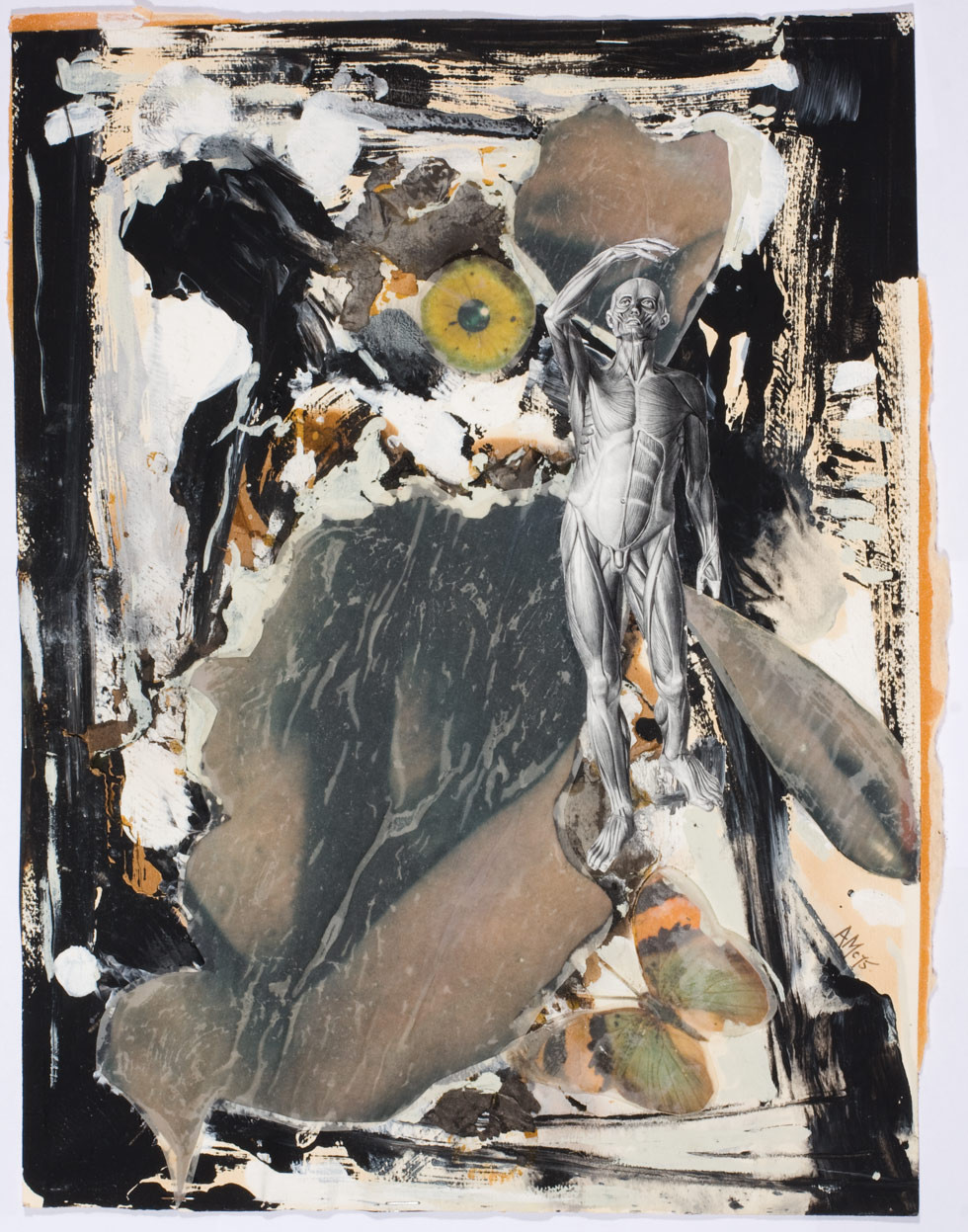

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Eye to Survival, 1975

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Eye to Survival, 1975Collection: Daniel Mudie Cunningham

I stretched out on the grass, my skull on a large, flat rock and my eyes staring straight up at the Milky Way, that strange breach of astral sperm and heavenly urine across the cranial vault formed by the ring of constellations: that open crack at the summit of the sky, apparently made of ammoniacal vapours shining in the immensity… a broken egg, a broken eye, or my own dazzled skull weighing down the rock, bouncing symmetrical images back to infinity.

— Georges Bataille

The disorienting, erotically charged images conjured by Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye (1928) could be the setting for any number of collages by Arthur McIntyre. Eye to Survival (1975) from the Survival and Decay Series provides a case in point. A naked male figure is frozen mid-step, the ground beneath has given way to ambiguously fleshy forms buttressed by the turbulence of gestural black brushstrokes. His flesh is stripped of skin exposing a cadaverous substratum of meat and veins. Gazing stoically into the distance, his right arm is raised high shielding his head from the sun even though it gives off little light. A butterfly flaps its wings sparking a dark storm within and beyond the picture plane. On closer inspection, the sun is actually an eye gouged from an unknown head and floating in space, omnisciently surveying a human condition where we compete for survival knowing that we cannot cheat decay.

This piece brilliantly sets the scene for McIntyre’s lifelong staging of the human condition in collages, paintings and drawings that obsessively chart the dualities of our existence: birth and death, light and dark, survival and decay. Big picture issues, rendered small at times, large at others, McIntyre bounced images back to infinity, knowing full well that the human condition is rarely as symmetrical as it is finite. When I took the collage out of its damaged frame another collage revealed itself verso, depicting a suntanned boy in red swimmers holding a pineapple next to a barely visible female figure. Their heads are severed by McIntyre’s scissors and glued down to the left of a set of framing instructions: “White Mount… Natural Timber…” The bright poolside light is stamped out by the brooding storm of Eye to Survival once framed. The boy with the pineapple is hidden away until now in a veritable closet of sexual desire. No wonder Elwyn Lynn once described McIntyre as a “master of theatrical montage”.

Arthur McIntyre: Bad Blood 1960-2000 surveys the work of this overlooked and often misunderstood artist. Why he was largely disregarded during his life is a complex question that relates as much to the ‘difficulty’ of some of his work, as it does the manner in which he could be a ‘difficult’ individual. His visceral engagement with the body is pumped with ‘bad blood’, the arterial life-force upon which his aesthetic and political concerns were based. The stain of ‘bad blood’ also emerges in the remarkable story of an artist and critic whose art world relationships were often marked by enmity. Spanning four decades, and comprised of loaned work from public, private, corporate collections and his estate, Bad Blood most of all, reveals McIntyre’s steadfast obsession with and compassion for the volatility of the human condition. It also makes known the rigour, discipline and fastidious technique of his work. Hazelhurst Regional Gallery is proud to realise Bad Blood as a major partnership with Macquarie University Art Gallery, where a companion ‘work on paper’ exhibition will be concurrently presented. Dispersed over both venues is a selection of what I believe are a group of important works that plot key stylistic shifts within McIntyre's extensive oeuvre. This publication – the first ever produced about McIntyre’s work – reproduces every work in Bad Blood as well as including Victor Rubin’s portrait of McIntyre and three works from the collections of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of Western Australia and Heide Museum of Modern Art that could not physically be included in the exhibition.

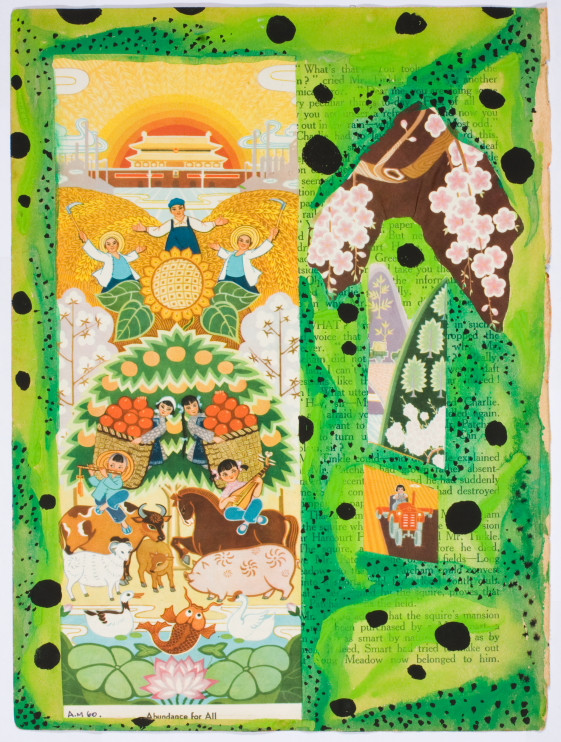

Arthur McIntyre, Abundance for All, 1960

Arthur McIntyre, Abundance for All, 1960Collection: National Gallery of Australia

Abundance for Argonauts

Arthur Milton McIntyre was born in 1945 and grew up in Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, where he spent much of his time drawing, listening to music and going to see up to three movies a week at the Savoy and the Trocadero Cinemas. If creativity is genetic, McIntyre inherited his love of art from his father and grandfather, both professional musicians who played in big bands. His father, Charles Thomas McIntyre, worked as a violinist on the RMS Niagara before it sank during World War II after striking a mine laid by the Germans in 1940. A ladies’ man with a taste for liquor, Charles played in Ella Fitzgerald’s band on the Niagara, just before she became famous.

When Charles met Lillian Atua Mills in 1945, she was a struggling single mother with a daughter to a failed first marriage. Charles and Lillian married like many others did at the time, because she was pregnant out of wedlock – with son Arthur. As part of the marriage agreement Charles quit his music career for a quieter life in Katoomba, where he ran a grocery store. Having served time in the war as a medical officer, Charles acted as something of a ‘faith healer’, happy to dole out potions and tonics to locals seduced by his roguish, boozy charm. A staunch communist who espoused his politics to anyone who would listen, it is surprising he was not greeted with greater suspicion and fear.

McIntyre’s earliest collages reference his father’s devout communism: “I first began using collage (mostly photographic) in 1960 in a series of small works on paper which deployed images from the Chinese propaganda magazine China Reconstructs, to which my father subscribed”.

Communism was not a shared interest between McIntyre’s parents; in fact, they had very little in common except ships. Lillian was born at sea, somewhere between Sydney and Fiji on The Atua, the ship from which her middle name derives and Charles gave up his shipping life to be with her. During her youth Lillian’s mother managed a chocolate factory in Summer Hill, in Sydney’s inner west, but she also spent a great deal of time at sea. As idyllic as a youth punctuated by oceans and chocolate sounds, Lillian suffered from an inherited bipolar disorder, which had also afflicted an uncle before her. Her uncle committed suicided in the 1920s by jumping off St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney where he worked as a doctor. In spite of her condition, McIntyre was a self-professed “mother’s boy”, who viewed his mother as “perfect” until her nervous breakdown in 1958 from which she never recovered.

McIntyre’s older half-sister, Lynne, loomed large in his imagination and he saw her in the same light as screen idols Jane Powell and Grace Kelly – his mother was “more of the Ida Lupino type”.

The tenuous marriage of his parents made for a difficult childhood with the rampant alcoholism of his father escalating as his mother’s mental state deteriorated. McIntyre would escape this domestic nightmare through fastidious commitment to his studies at Katoomba High School, where he completed the Leaving Certificate in 1962 as the Dux of the school. Some years earlier at the age of 13, McIntyre’s poem “A Picture in the Gallery” was published in the school’s magazine Outlook (1958), signposting his later career as an artist and writer:

Her figure was so round and plump—

As is the way with many a thing—

Her hand was resting on a stump,

And on her finger was a ring,

A green and shining lump.

Her face was stern and cold,

Oh! What an ugly scene!

Her clothes were ragged and old.

The artist with his brush had been

So very, very bold!

During his teens, an outlet for his growing obsession with art was the popular Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) radio program The Argonauts Club. Inspired by the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts and dubbed by the ABC as “The Art Gallery of the Air”,

McIntyre was offered two scholarships upon finishing high school and chose to study at the Alexander Mackie Teachers’ College of Advanced Education, which was affiliated with Sydney’s National Art School. On the first day at college, McIntyre met his lifelong friend Brian Phipps. “He was extremely nattily dressed, far more than anyone else”, recalls Phipps. “He had a green suit on and a yellow tie and he looked very handsome but with a surly look”.

Two works are included from this period in Bad Blood. Walkie Talkie (1963) is reminiscent of the free associative drawing style McIntyre mastered in sketchbooks in the late 1980s and nineties. Rainy Day in Paddington (1963) was found in McIntyre’s estate with a note declaring that he painted it “with David Strachan hanging over my shoulder!” Strachan was aligned with the Sydney Charm School, an appealing and saleable coterie of figurative painters that included Donald Friend and Margaret Olley. Though McIntyre repeatedly criticised the Charm School,

More influential on McIntyre, however, were late modernist art movements such as abstract expressionism and pop, which were later synthesised in his painting and collage practice. While teaching art in various Sydney and Canberra high schools for several years after college, McIntyre regularly exposed his students to contemporary art of the time, much to the dismay of more conservative colleagues. Patrick Faulkner was taught by McIntyre at Sydney Boys High in 1970 and was later encouraged by McIntyre as he set out to establish himself as a professional artist. Faulkner recalls that McIntyre appealed to his students because of his charismatic teaching style and Warren Beatty good looks.

Arthur McIntyre, Cloudy Day Feeling, 1972

Arthur McIntyre, Cloudy Day Feeling, 1972Collection: Penrith Regional Gallery

Slide from Womb to Tomb

Though some early 1960s works have been included, Bad Blood mostly comprises work dating from the seventies, reflecting the time McIntyre came to public prominence. His first exhibitions held between 1970 and 1973 consisted mostly of hard-edge paintings, mirroring the late sixties rage for colourfield abstraction in Australian art. Of the seminal exhibition The Field, held at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in 1968, Patrick McCaughey argues that the examples of New Abstraction exhibited therein, showed “a fundamental difference between Sydney and Melbourne painters” and describes the Sydney painters’ works as “hard-edge, non-referential, urbane art objects which were produced by a travelled group of artists returning from overseas” in contrast to Melbourne painters whose works were “referential [and] abstracted from their immediate suburban environment”.

For his 1971 solo exhibitions at Gill Gallery in Armidale and Nth Degree Gallery in Paddington (now the location of Savill Galleries), McIntyre exhibited under the pseudonym Adam Milton for reasons that remain unclear. James Gleeson, who later awarded McIntyre the Kedumba award in 1993, described Milton’s hard-edge work in The Sun as “cool and carefully calculated”, rightly pointing out a technique “based on the idea of masking a white surface with strips, pieces of knotted string, etc, and then spraying it with black paint”.

“Australian artists cannot be said to have extended modernism in comparable ways to those of their American contemporaries”, writes Richard Haese in Rebels and Precursors. “They did, however, succeed in turning it to their own unique ends”.

Christine Dean, writing on another overlooked artist of the period, Peter Upward, rightly notes that “the term ‘abstract expressionism’ is misleading when applied to Australian art primarily because Australian artists working in this style had no direct contact with the origins of this movement”.

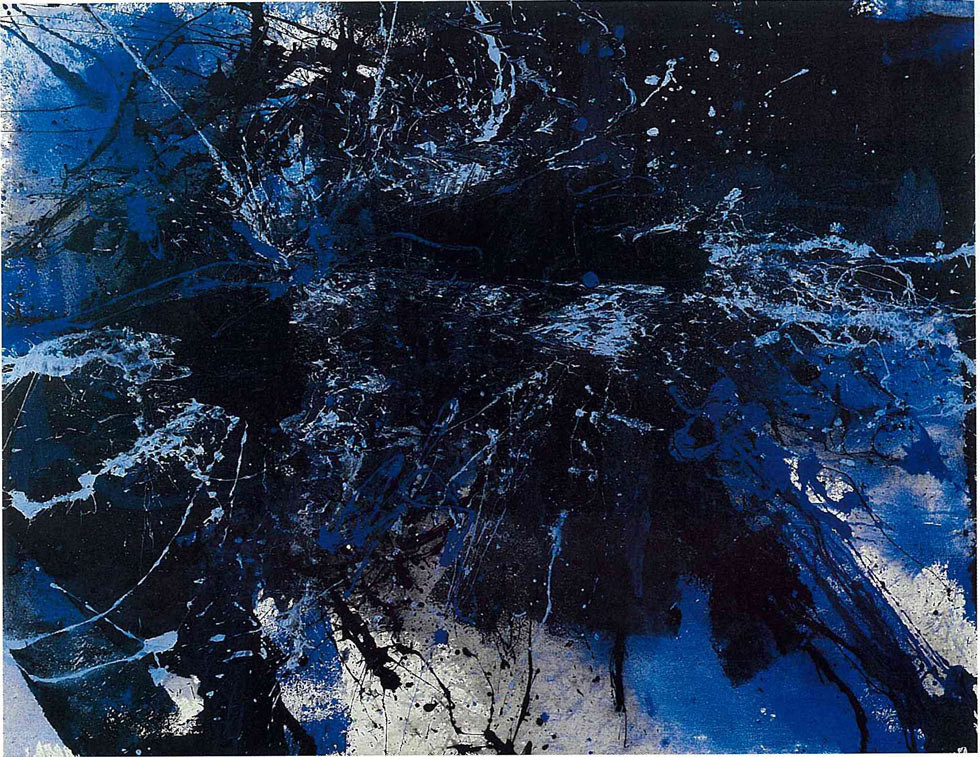

The earliest gesture towards abstract expressionism in Bad Blood can be found in Cloudy Day Feeling (1972), a melancholy vortex of white, grey and black brushstrokes. Its affective intensity is heightened by the furious intersection of sharp painterly marks poised on the edge of a black bottomless void. Typical of bipolar disorder, seasonal and environmental shifts often underscored the emotional tenor of individual works. Illustrated here, but not included in Bad Blood, is Origins (1973) held in the Art Gallery of Western Australia collection. When this piece was exhibited in the Gallery’s Recent Acquisitions show in 1974, Perth art critic Murray Mason, remarked that Origins was “particularly striking with [its] controlled patternings achieved through delicate dribbles and runs and splashes”.

Arthur McIntyre, Aquamarine, 1973/74

Arthur McIntyre, Aquamarine, 1973/74Collection: Trinity Grammar School

1975 was a watershed year for McIntyre in many ways. In February he held an important exhibition Slide Series ‘75 at Holdsworth Galleries. He wasn’t able to attend the opening because he left Australia in January to undertake a residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts studio in Paris, then governed by the Power Institute at the University of Sydney. Significantly, it was the move overseas that allowed him to quit teaching and become a full-time artist. Four of the Slide paintings were acquired by public collections: The Power Institute, Queensland Art Gallery, Macquarie University and the University of New South Wales, while several others were purchased for private collections. In many ways, Slide Series, with its muted, earthy tones signalled the endpoint of McIntyre’s more formal exercises in painterly gestural abstraction. Sunday Telegraph art critic W.E. Pidgeon wrote: “Arthur McIntyre, a stark black, brown and white action man, views the world as slithery outpourings or eruptions of incandescence over the darkness of chaos”.

Spending a year away in Paris influenced his approach to making art. Due to the financial and logistical constraints of working abroad and having to send work back to Australia for exhibition, McIntyre worked on a smaller scale and more on paper than canvas or board. Collage became a primary medium in response to his view of Paris as a decaying city, textured by peeling layers of transition between its past and present. “Somehow Paris itself seemed to me like a collage. Everywhere I looked there was decay and mildew and it was the middle of winter and there were posters peeling off walls. Paris was made up of layer upon layer of textures which symbolised various histories and changes which had taken place”.

Even though McIntyre had regularly used collage up until this point, it is possible that Carl Plate, who was living in Paris at the time, also influenced his principal focus on collage. Stanislaus Rapotec was also residing in Paris in 1975, and in letters to friend Sylvia Laurent, McIntyre describes several soirees he attended with Plate, Rapotec and their respective wives. Plate was making many of his linear multiple strip collages, which were collectively exhibited for the first time ever in the exhibition Carl Plate: Collage 1938-1976 at Hazelhurst Regional Gallery in 2009. In a tribute written for the journal, Aspect: Art and Literature, after Plate died, McIntyre writes:

In 1968, [Carl Plate] was the first appointee to the Sydney University Power Bequest studio at the Cité Internationale des Arts, in Paris, where he later occupied other studio spaces. On one of these occasions (early 1975), I first encountered Plate, who, although fighting a brave battle with serious illness, still found plenty of time to offer a warm hand of friendship to a young artist slightly overwhelmed by his first experience of life in a strange and often hostile European capital.

At this time, Plate was working mainly on a series of small collages and paintings developed from the original cutting and pasting processes… The collage process was a familiar one for an artist who had often used it as a means of determining ideas for compositions prior to sometimes quite large scale paintings. Because he spent so much time travelling, the intimate nature and scale of collage was particularly convenient.

A small pastel sketch titled Paris Grey (1975) – a throwback to the organic abstract forms of the Slide Series and not indicative of his predominant embrace of collage – was found in his estate with a note declaring: “Many similar drawings from this period were left in the care of Carl and Jocelyn Plate, who were also in Paris. When Carl died, my drawings were lost in the ensuing chaos!” Among the other artists he befriended in Europe was the late Swedish painter, Ulla Waller. Ever the cinephile, McIntyre relished the opportunity in August 1975 to stay at her seventeenth century Stockholm mansion that had been used as the set of Sidney Lumet’s film adaptation of Chekhov’s The Seagull (1968). At this time, McIntyre also met the Swedish composer Ragnar Grippe, who set an experimental electronic score to a film depicting McIntyre’s paintings.

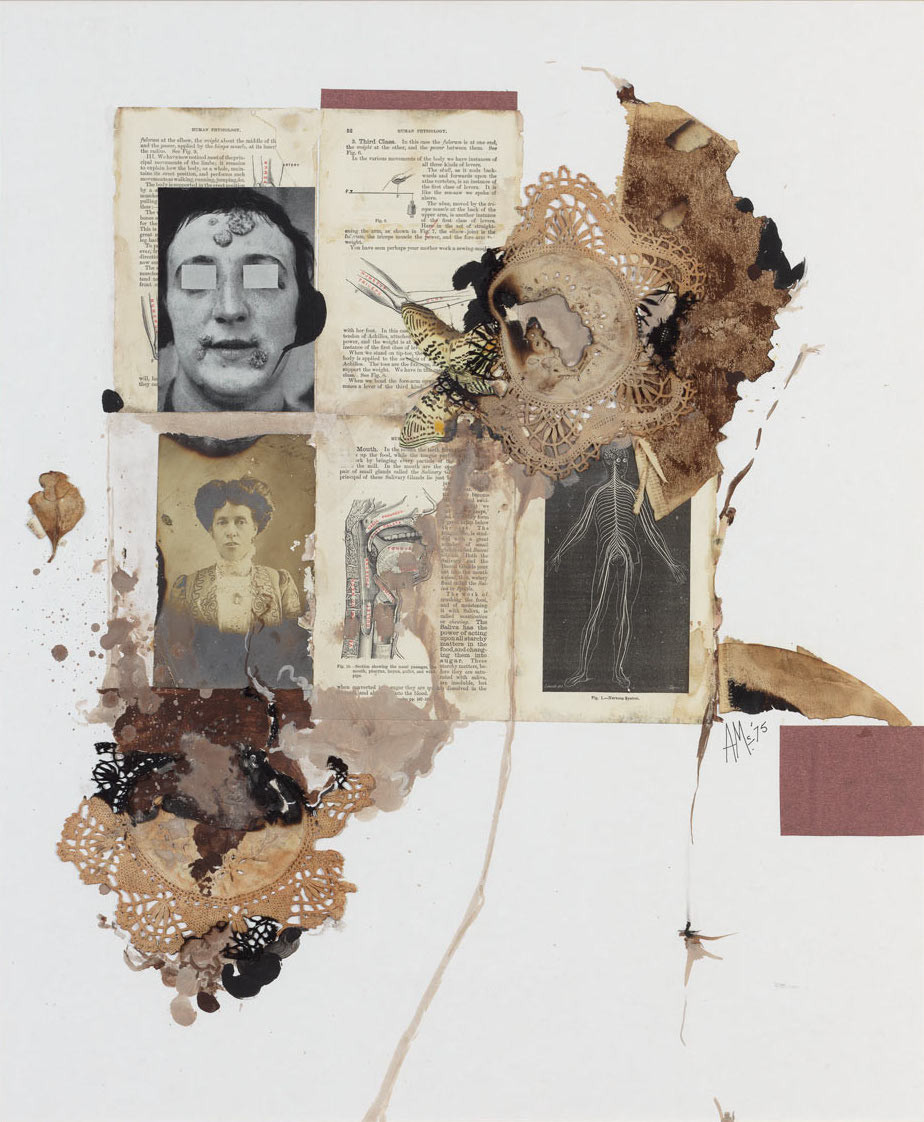

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Syphilis and Old Lace, 1975

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Syphilis and Old Lace, 1975Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

Many of the Paris collages, which collectively formed the landmark Survival and Decay Series, were exhibited in a group exhibition at the Salles Sandoz in the Cité Internationale des Arts in May 1975. The Survival and Decay Series are unsettling collages that juxtapose images of erotica with medical photos of body parts often ravaged by sexually transmitted diseases. In many ways they preempted the AIDS crisis that was about to erupt globally. In 1990 McIntyre claimed that Survival and Decay Series “was hideously prophetic in our age of AIDS. My intention was never to preach or moralise… I was simply intrigued that so much suffering can result from acts of love – and by notions related to pleasure, pain and death”.

Between 1976 and 1979, McIntyre held several solo exhibitions in Australia with variations on survival and decay themes, though his focus narrowed with the Survival Series. It was here that McIntyre examined the vulnerability and, as one critic put it, the “fleshy destiny of human beings from womb to tomb”.

McIntyre was no stranger to bad press – from time to time his work was unfavourably received. Likewise he was no stranger to creating bad press that would in effect generate bad blood. To supplement his income, he started publishing art criticism in Art & Australia from 1975, The Australian from 1977 to 1978 and The Age from 1980 to 1989. In 1978 McIntyre and Andrew Fowler co-wrote an article for The Australian alleging that several of the “Jackson Pollock” paintings hanging at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery in Sydney were in fact fakes. The front page article was published under the name of Andrew Fowler and fellow art critic Sandra McGrath – though McIntyre did receive a writer’s fee of $50 for the article and he went on to publish his full story on the incident in the UK edition of Art Monthly.

The fallout from the Pollock scandal lingered long for McIntyre. According to McIntyre’s closest friends, he received numerous death threats and changed his phone number several times after it happened. He also lost his job at The Australian. McIntyre notes in his diaries that the newspaper’s arts editor, the renowned soprano Maria Prerauer, offered him an ultimatum when Ronald Millar submitted a favourable review of Survival Series ‘78: Womb Struck. According to McIntyre, Prerauer “told me I had a choice to make: she would run the review if I resigned, or she would not run it and I could keep my job”.

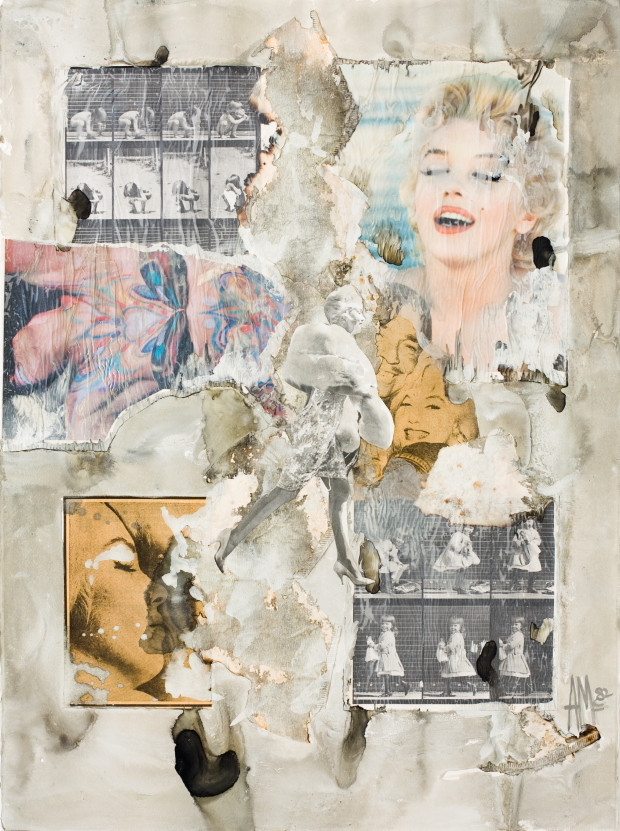

Arthur McIntyre, Phallusies, 1982

Arthur McIntyre, Phallusies, 1982Private Collection

Scraping Away the DNA

While the seventies were a time when McIntyre was working through his twin obsessions of abstraction and pop through painting and collage, the eighties were a time where it was refined with an aggressive, no holds barred energy. What most characterises his output during the eighties was a continuation of survival themed collages and oil stick studies of the human head. The influence of pop imagery was amplified in Phallusies Series (1982-83), through the use of Marilyn Monroe magazine portraits, Eadweard Muybridge’s nineteenth century motion study photographs and the now common integration of diseased body parts with sexual imagery. Skin is simulated in these collages through the textures brought about from layering tissue and translucent drafting papers. The influence of artists like Mike Brown and Richard Larter is evident in Phallusies Series and persists through to the 1990s.

In 1983, McIntyre bought and moved into a large heritage-listed house in Croydon, in Sydney’s inner west, with Brian Phipps and criminal psychiatrist Dr Ken Mackey. McIntyre rebuilt the large garage into a studio and worked there for the rest of his life. Jo Holder recalls visiting McIntyre’s home and studio in anticipation of a 1985 solo exhibition at Mori Gallery, then also located in the inner west: “Stephen [Mori] and I visited Arthur’s impressive Arts & Crafts house in Croydon and discussed the works in the large upstairs bedroom which was reminiscent of visiting another art legend, Martin Sharpe: a faintly gothic air. These large framed drawings had a similar haunted air – but with a gestural transavantgardia quality, the eighties being the big brush time”.

After the Mori Gallery exhibition Painting into Drawing, for which he showed the large monochromatic works Holder describes, McIntyre decreased the scale while switching on the wit for a head studies series for the 1986 solo exhibition Portraits of the Age of Mechanical Parody at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne. The Scholar, The Confidante and A Man of Influence (all 1986) have been selected to represent this period in Bad Blood. McIntyre’s study of the human head is perhaps the most compulsive facet of his entire oeuvre. “I believe it is the most fascinating subject of all for an artist, because I view the human head as a type of container for everything that we comprehend about life”.

Arthur McIntyre, Head After Shock Treatment, 1992

Arthur McIntyre, Head After Shock Treatment, 1992Collection: National Gallery of Australia

McIntyre never explicitly linked his own illness with the head studies; to do so would have risked couching his work with retrograde ideas of tortured genius being channelled through artistic expression. As he was well known for ongoing themes of human survival and decay, McIntyre had strategically detached an obvious likeness of himself in the work for more anonymous or neutral depictions of the human head. In the early Survival and Decay Series, the anonymity of the collaged pictures from medical or porn sources are enhanced by their severed heads, cut-out eyes and dismembered limbs. It seems the collage process scrapes away all traces of DNA and his anonymous figures metonymically stand in for us all. The human condition, with its paradoxes and foibles, is the bigger picture for McIntyre and within it the individual is ultimately obliterated.

Nowhere is this abolition of the self more prescient than with the onset of the AIDS crisis in the mid-eighties with its horrific Grim Reaper body count connotations. By representing sex and disease since the 1970s, McIntyre was the first artist in Australia to reverberate the paradigm shift in how we would come to think about and represent sexuality in the burgeoning age of AIDS. McIntyre’s solo show Riddle of the Tombs (1987), made an unequivocal statement about the global spread of AIDS by referencing the mass graves of London’s Black Plague and a South Australian discovery of a grave containing “embracing” skeletons. Drawn in oil stick and charcoal, McIntyre’s skulls and bones were installed at Holdsworth Contemporary Galleries behind several coffins, prompting some distressed viewers to flee the gallery. McIntyre notes in his diaries that the Survival and Decay Series provoked similar reactions ten years earlier and just before the panic of AIDS had set in.

Arthur McIntyre, Skulls Series and Riddle of the Tombs, 1987

Arthur McIntyre, Skulls Series and Riddle of the Tombs, 1987Collections: Heide (Skulls) and QAGOMA (Riddle of the Tombs)

Photo: Silversalt

Elwyn Lynn wrote of the Skull Series: “some like helmets, some like cubism with a dash of metaphysics but all individual and powerful and savagely sculpturesque”.

McIntyre never contracted HIV or AIDS however he was in and out of hospitals from the late-1980s and his work increasingly responded to themes of illness and mortality. McIntyre created a small sketchbook of 80 drawings called Ward 16, Sydney Hospital (1989) while recovering from abdominal surgery. Andrew Sayers included the sketchbook in Artists in Hospitals at the Drill Hall Gallery, then governed by the NGA, who had purchased it for their collection.

McIntyre’s last solo exhibition of the decade, Art for Art’s Sake at Holdsworth Contemporary Galleries in 1988, let the light back in. Amid the darkness of the AIDS epidemic and his own health battles, this show was decidedly optimistic. Elwyn Lynn praised the exhibition saying, “McIntyre’s attitude is summed up in the title [of one painting] The Bearable Lightness of Being: he is intent to exorcise gloomy thoughts, especially with the help of Orphism and, in the last of the Solarium Series, with a prod from Kandinsky and maybe Kupka into realms of pulsating freedom. Others look delicate and throb frailly with muted hues like whispers”.

Arthur McIntyre, East Meets West, 1988

Arthur McIntyre, East Meets West, 1988Collection: National Gallery of Victoria

Reform School Charm

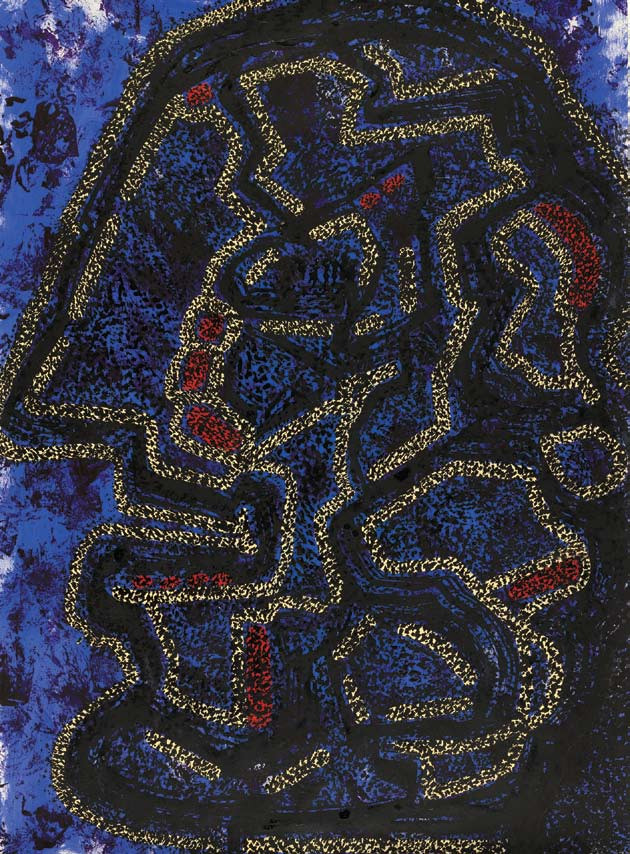

The explosive pleasures of paint dominated McIntyre’s work in the 1990s and he increasingly worked on large canvases, while maintaining a voluminous output of small mixed media works on paper. Brother/Sister and Nervous Nelly Bears Witness III (both 1992) are masterful examples of this new direction, while also maintaining his fascination with collage and depictions of the human head.

Another notable style of this period was a topological method of patterning that achieved airborne depictions of territories viewed from above. McIntyre was awarded the Kedumba Prize for one such work, Recollections of a Blue Mountains Childhood (An aerial perspective) in 1993.

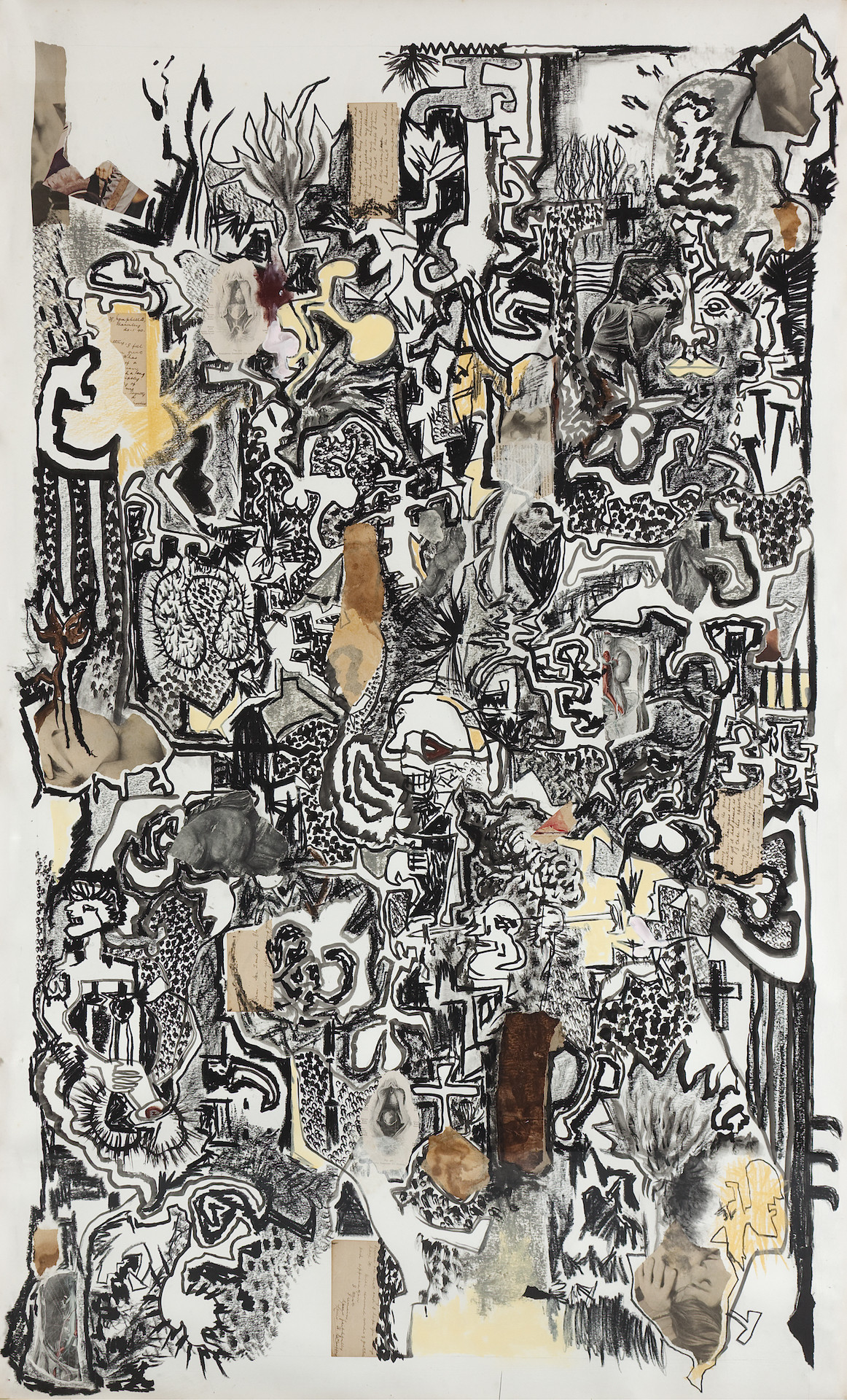

McIntyre’s painting practice peaked with the Life, Sex, Death, Décor series of 1994-95. It was here McIntyre merged intricate patterning with frenzied applications of magazine collage, some of it pornographic. The decorative engagement with surface was his wry revisionist response to the paintings of the Sydney Charm School. “As you begin to manipulate the surface of a painting, you’re playing around with decoration, whether you admit it or not,” McIntyre explained in The Australian. “What I’ve done in this current exhibition is attempt to reinterpret my preoccupations with sex and death and the darker side of life with references – some of them in-jokes, if you like – to the tradition of the Sydney charm school… There’s a lot of colour, there’s a lot of movement, there’s a lot of surface allure.”

Arthur McIntyre, Someone Else’s Life, 1994

Arthur McIntyre, Someone Else’s Life, 1994Collection: Penrith Regional Gallery

McIntyre mostly ceased writing after his second book Contemporary Australian Collage and its Origins was published in 1990, to focus on his studio practice. The decision to do so was largely inspired by James Mollison, who had announced plans to hold a mid-career survey of McIntyre’s work at the NGV after visiting McIntyre’s studio in February 1991. It never came to pass as the corporate sponsor for the planned survey, Ericsson, withdrew in favour of a sports event. Mollison’s support, however, was unwavering. His last professional speaking engagement before retiring from the NGV was to deliver a speech at the opening of Life, Sex, Death, Décor at Holdsworth Galleries on 1 July 1995:

I have noticed over the years how the successive waves of world art have been reflected in what Arthur McIntyre has done. The work occasionally grew bare and simple. Occasionally, it was very gestural. It reflected everybody’s interest in the images you can pick up from the world around you and stick down onto a canvas, or a piece of paper. I could also notice the way in which he is heir to a great deal of what has gone on in Sydney during his lifetime, and mine. I believe that we have here a painter who has taken in the message of the painterly aspects of Sydney painting over a very long period of time. The example of Fairweather is with us on the walls today, and the energy of the Annandale Imitation Realists is here today. The energy that you also find in the work of Olsen and Klippel, is represented through all of the paintings in this exhibition.

Arthur McIntyre, Life, Sex, Death, Décor I, 1994-95

Arthur McIntyre, Life, Sex, Death, Décor I, 1994-95Collection: National Gallery of Australia

Meat for McIntyre

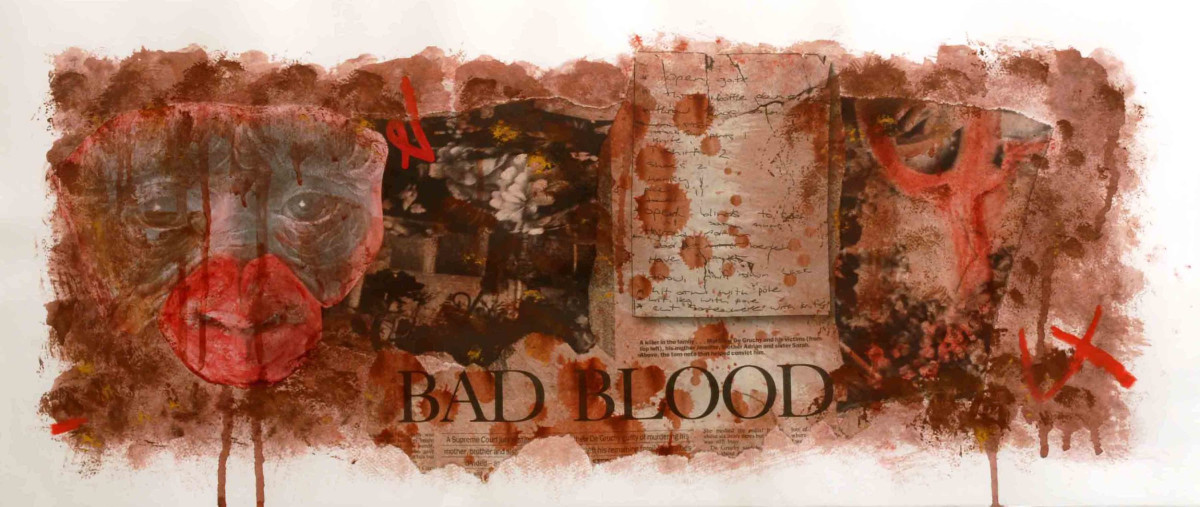

Survival and decay are themes that shaped McIntyre’s life as much as his work. Bad blood dominated his connections in Sydney and it is interesting that Mollison, or the curators that included him in important exhibitions such as Ted Gott or Andrew Sayers, were not Sydney-based. For many Sydney gallery directors, who could have forged important inroads for McIntyre into public collections and exhibitions, the bad blood had well and truly coagulated. It is unsurprising that blood – so necessary for survival, so intrinsic to our decay – recurs in his work throughout the last decade he made art. Bad blood is there in AIDS Suite (1993), in the use of ox blood as paint in Arterial Connections, Arterial Detours and Blood Lust (all 1996) as well as in the true crime collages Bad Blood, Investigation and Excavation (all 1999).

It has been almost three years since I began researching McIntyre for this survey, Bad Blood. While poring over the vast archive of letters, writings and neglected artworks held in his estate, I could not help but feel that decay had well and truly set in: “When I am dying I want to be able to look around at mountains of work”, writes McIntyre. “It does not bother me that much of it will be rotting and providing fodder for insects”.

Arthur McIntyre, Bad Blood, 1999

Arthur McIntyre, Bad Blood, 1999Collection: Wollongong Art Gallery

After the cancellation of the NGV survey, McIntyre’s enormous output continued, though he rarely exhibited and public interest in his work waned. Many close to him, including enduring friends Brian Phipps, Peter Phillips, Peter Kyle, Sylvia Laurent, June Lewis, Patrick Faulkner, Ken Mackey and retired Holdsworth Galleries director Gisella Scheinberg, believe the NGV setback and a rejected application for an Order of Australia that James Gleeson refereed, accelerated his deteriorating mental health and alcoholism. After a suicide attempt in 2000, McIntyre submitted to ECT like his mother and sister before him, despite vows he never would. A few works were made prior to his treatment in early 2000 including the collages Meat for Bill. These works circuitously reference the survival and decay motifs of the 1970s alongside pop culture references to hero of literary cut-and-paste, William Burroughs. McIntyre ceased making work around the time these collages were produced because, as Phipps explains, the ECT “zapped his brain”, making it impossible for him to do anything except consume a steady diet of alcohol and prescribed psychiatric drugs.

Three years later on 26 October 2003, Arthur McIntyre was dead from heart failure, five days before his fifty-eighth birthday. Brian Phipps found him two days after the coroner’s assumed date of death, alone and naked on his bedroom floor. Exactly 40 years had passed since they had first met at the Alexander Mackie Teachers’ College.

Of his last solo exhibition, Vicissitudes, held at the now defunct gallery DQ on Oxford in 1997, Bruce James summed up the man and his work like no other:

For stamina alone, McIntyre is surely a legend of Australian art. There can be few of his peers who have adhered with such consistency of purpose to a single vision. His practice, largely in the collage medium he has found so fruitful for so long, is built around a corporal conception of the world. Like Leonardo, he measures humanity by its limbs. He also recalls that most in his reverence for the human form. Though McIntyre’s bodies are sometimes blighted to the point of cadaverousness – his interest in pathology is inveterate – they never advance into view without the grace mark of compassion.

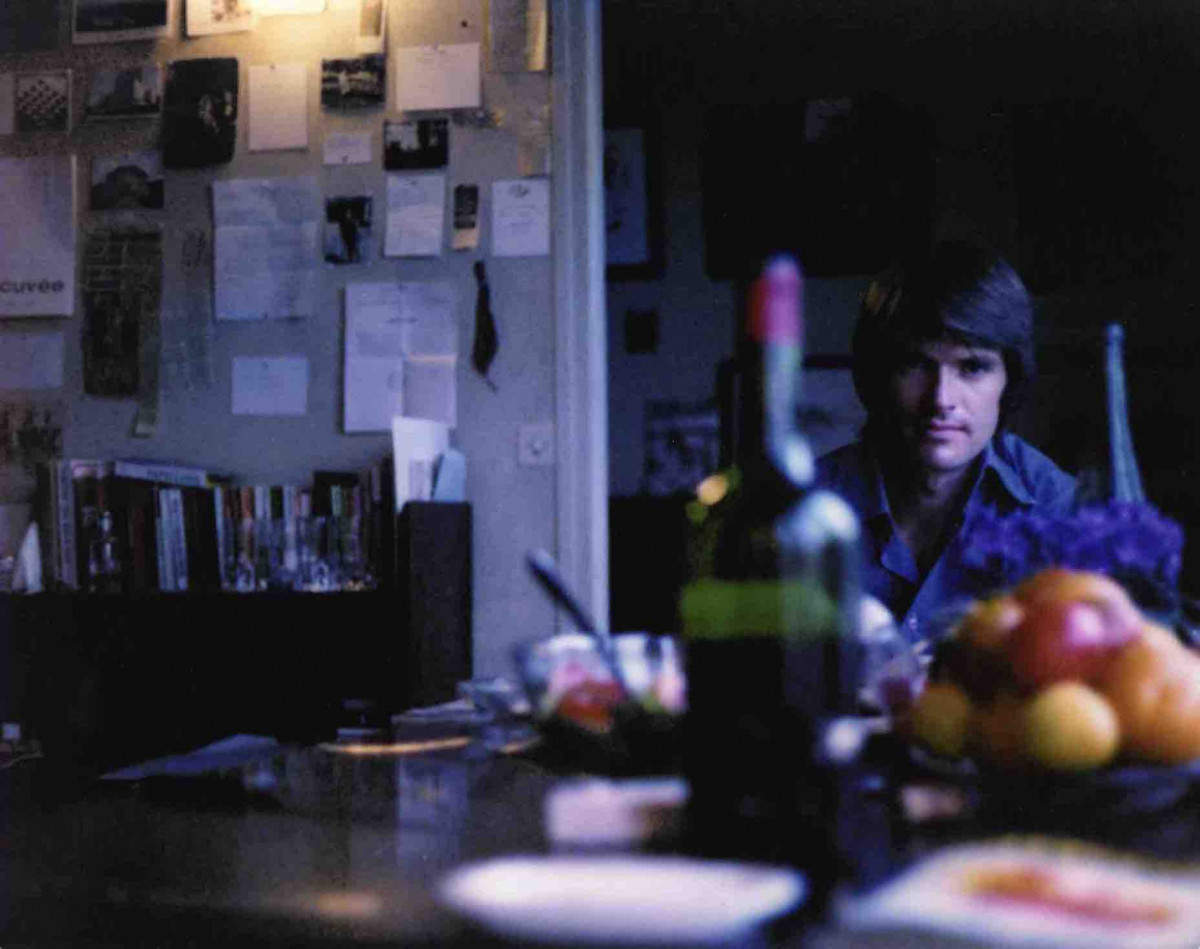

Arthur McIntyre in residence at Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 1975

Arthur McIntyre in residence at Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 1975- Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye [1928], trans. Joachim Neugroschal, Penguin, London, 1982, p.42

- Elwyn Lynn, “Archly hewn Huon”, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 27-28 September 1986, p.10

- Arthur McIntyre, “Collage: Australian collage in context”, Oz Arts, Issue 10, 1994, pp.88-93

- Arthur McIntyre, diary note, 16 August 1996

- Arthur McIntyre, diary note titled “For My Sister-By-Half”, 26 June 1996

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jeffrey Smart, Not Quite Straight: A memoir, Vintage Books, Sydney, 1996, revised 2008, p.295

- Rob Johnson, “The Golden Age of the Argonauts”, Sydney Morning Herald – Good Weekend, 14 September 1996, p.14

- “Art collection from child painters”, Qantas Empire Airways, vol.27, no.5, May 1961, pp.10-11

- Brian Phipps in conversation with the author, 7 January 2010

- Arthur McIntyre, “Problems in turning on the charm”, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 16-17 July 1977, p.9; Matthew Westwood, “Youthful energy drawn out of blue”, The Australian, 30 June 1995, p.15

- Patrick Faulkner in conversation with the author, 30 December 2009

- Patrick McCaughey, “The Transition from ‘Field’ to Court”, Australian Art 1960-1986: Field to Figuration, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987

- James Gleeson, “Art Review”, The Sun, 30 June 1971, p.42

- Richard Haese, Rebels and Precursors: The Revolutionary Years of Australian Art, Allen Lane, Ringwood, Victoria, 1981, pp.viii-ix

- Christine Dean, Frozen Gestures: The Art of Peter Upward, Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest, Emu Plains, NSW, 2007, p.12

- Murray Mason, “The Arts”, The West Australian, 8 December 1973

- W.E. Pidgeon, “Heavyweights”, Sunday Telegraph, 16 February 1975, p.93

- Sandra McGrath, “The last image is of the bush”, The Australian, 8 February 1975, p.16

- Bronwyn Watson, “Art of Arthur McIntyre – a profile”, Oz Arts, Issue 1, 1991, p.20

- Arthur McIntyre, “Carl Plate – a personal tribute”, Aspect: Art and Literature, vol.4 no.4, 1980, p.64

- Arthur McIntyre, Contemporary Australian Collage and its Origins, Craftsman House, Roseville, NSW, 1990, p.130

- Ronald Millar, “Identity search”, The Australian, 20 April 1978, p.8

- Nancy Borlase, “Mainstream paintings alive and well”, Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 4 March 1976, p.7

- Nancy Borlase, “McIntyre’s new breadth of vision”, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1977, p.7

- David Apelbaum, “Blood, Guts & Gore: is this the new art(?) form?”, Campaign, no.18, March 1977, p.36

- Sandra McGrath & Andrew Fowler, “Pollocks fake, says art expert”, The Australian, 4 May 1978, p.1; Arthur McIntyre, “Fake Pollocks fool Australian art establishment”, Art Monthly [UK], no.18 July/August 1978, pp.4-6

- Arthur McIntyre, diary note titled “Prompted by the death of Elwyn Lynn”, 22 January 1997

- “Soprano Maria Prerauer dies”, ABC News, 31 May 2006

- Giselle Antmann in conversation with the author, 31 January 2010

- Jo Holder, email to the author, 22 January 2010. McIntyre surveyed the burgeoning art scene of Sydney’s inner west and Mori Gallery’s place within it at the time, in “East is east, and West is where it’s gone in the Sydney art world”, The Age, 21 April 1984

- Arthur McIntyre, “Drawing is a State of Mind!”, Australian Artist, no.90, December 1991, p.46

- Nancy Corbett, “Angels & Demons Heroes & Villains”, Oz Arts, Issue 6, 1993, p.90

- Elwyn Lynn, “John Perceval: a first for Sydney”, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 27-28 June 1987, p.12

- Leo Steinberg, “The Skulls of Picasso”, Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, Oxford University Press, New York, 1975, p.118

- Sasha Grishin, “Restraint replaces horror”, Canberra Times, 6 December 1994

- Elwyn Lynn, “The exorcists and the Renaissance’, The Weekend Australian – Weekend, 22-23 October 1988, p.15

- Arthur McIntyre, “Drawing is a State of Mind!”, Australian Artist, no.90, December 1991, p.44

- Matthew Westwood, “Youthful energy drawn out of blue”, The Australian, 30 June 1995, p.15

- Transcript from video recording of James Mollison speaking at the official opening of Arthur McIntyre’s solo exhibition Life, Sex, Death, Décor at Holdsworth Galleries on 1 July 1995

- Arthur McIntyre, artist statement titled “My Art is as Intimate as Fucking”, April 1995

- Brian Phipps in conversation with the author, 7 January 2010

- Bruce James, “Limbs like Leonardo”, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 August 1997, p.14

Curatorial text for book monograph published on the occasion of Arthur McIntyre: Bad Blood 1960–2000 at Hazelhurst Arts Centre, 15 May – 27 June 2010, and Macquarie University Art Gallery, 19 May – 26 June 2010.

Published by Hazelhurst Arts Centre in 2010.