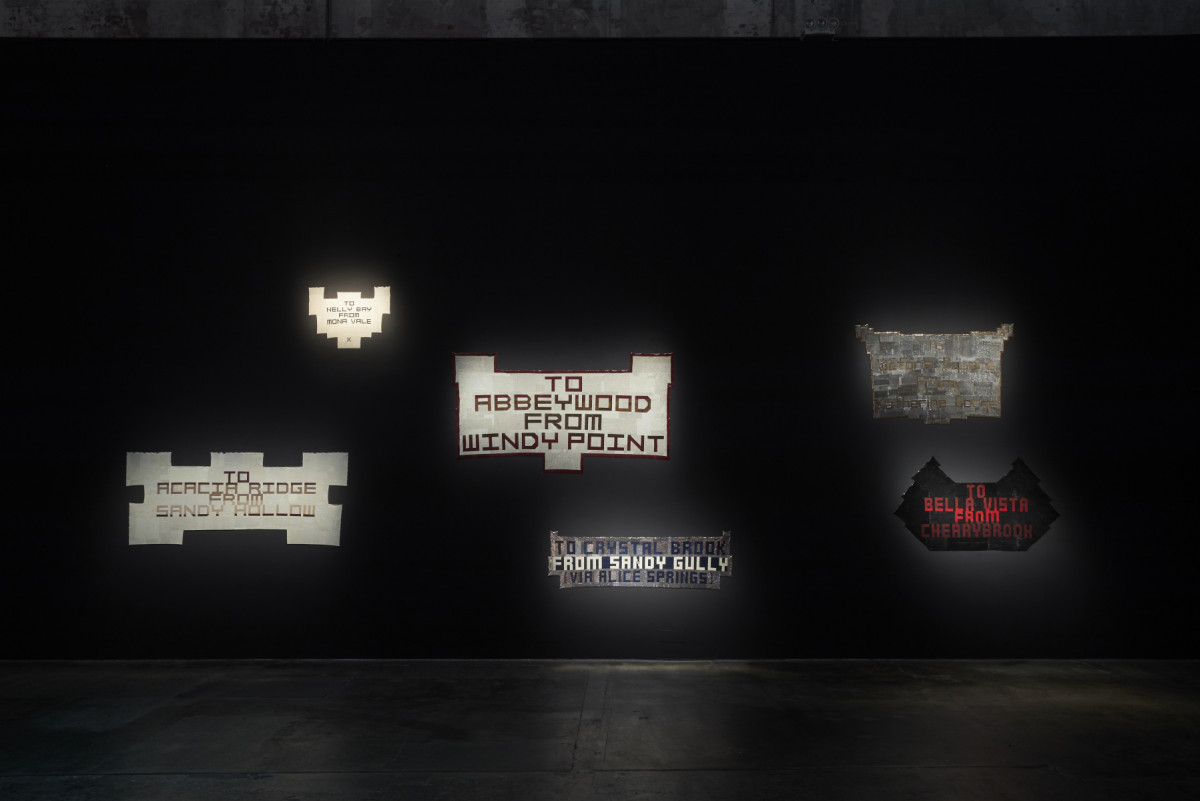

Troy-Anthony Baylis, Postcards, 2010-19.

Troy-Anthony Baylis, Postcards, 2010-19. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Zan Wimberley

The word is land and land is the word. The manner by which land is named, and how we become named (made accountable) in the process, informs the thinking behind the recent work of artist Troy-Anthony Baylis. ‘If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes’, said French filmmaker Agnès Varda. I am certain she was talking about Australian artist Troy-Anthony Baylis, a descendant of the Jawoyn people from the Northern Territory and also of Irish ancestry. Cut this artist open and out would pour the blood and guts of Country, framed by the ‘song lines’ of a three-minute pop ballad. Puns on Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal conceptions of Songlines and Dreamings frame works that remix queer aesthetics and pop culture as a decolonising strategy to reconcile multiple perspectives of Country with new stories.

Nomenclatures at the Art Gallery of South Australia brings together three major bodies of text-based work: Postcard, Nomenclature, and Tell Them Their Dreaming. Baylis rigorously unpacks meaning from the words his letterforms speak, doing so through the inventive artisanal materiality of his practice.

The narrative for this exhibition starts with Postcard, an ongoing series begun by Baylis in 2010. Metallic Glomesh and faux-mesh handbags and purses from second-hand stores are repurposed to spell out place names while visually referencing Aboriginal breastplates. These breastplates were used during early colonial rule to conquer and divide, by singling out Aboriginal people and anointing a select few as supreme.

In a queer reimagining of the breastplate, Baylis rewrites Indigenous sovereignty by anointing Blak queens. In the intense and laborious process of reworking the glitzy fabric there is an implied correspondence between the drag queens and ‘sistagirls’ and the locations where they reside, or after which they are named. In this sense, ‘To Nelly Bay from Mona Vale’ can be read as a postcard between two queens, Nelly and Mona, as much as it could trace the Google-mappable locations of Nelly Bay in Queensland and Mona Vale in New South Wales. Like a postcard, these textual ‘breastplates’ connect sites of survival and resistance on Country to remap the past for the future.

In 2019, six of the Postcard works were presented on Gadigal land in The National: New Australian Art at Carriageworks in Sydney. Soon after The National opened, Baylis was awarded the inaugural Guildhouse Fellowship, enabling him to travel and make new work. As part of his fellowship itinerary, two months were spent living in Berlin, where the logic of the Postcard series branched out into other ideas around the mapping of Australian land to language but through the lens of his time spent in Germany.

Having now lived and worked for two decades in Adelaide, Baylis is familiar with his adopted home city and its Aboriginal histories. The opportunity for travel and research opened up new connections. He became curious about the history of why certain towns in South Australia and elsewhere across the nation had multiple names: they were first given German names, later renamed with non-German names, in some cases renamed again, arriving at the names by which we now know them.

Towards the end of the First World War, the South Australian Government introduced the Nomenclature Act 1917. Prompted by anti-German sentiment, the Act anglicises places that had been given German names following the settlement of German immigrants, which began as early as 1838. Later, in 1935, just prior to the Second World War, a new Act reinstated a few of the abandoned German names, including Klemzig, Hahndorf and Lobethal. The irony is that some of the replacement non-German names had German significance – Klemzig’s renaming as Gaza, a case in point.

In response to this history, Baylis has produced Nomenclature, a bold new series that attempts to reconcile the dual appellations of these places with Aboriginal names for Country. Through weaving and stitching, Baylis combines these words in large textile works, referred by him as ‘landscapes’. As part of the process, he paints the two non-Aboriginal names onto large canvases that were originally new and second-hand domestic holland blinds. Then he cuts one in long strips, the other in short strips and weaves them back together – a layering of the land.

Baylis says: ‘If you think about weaving, you have the warp and the weft, it’s about tension and how you suspend that tension. What’s constantly in suspension are these histories of place and meanings of place’.

Troy-Anthony Baylis, Nomenclature (Klemzig), 2020

Troy-Anthony Baylis, Nomenclature (Klemzig), 2020Courtesy of the artist

Over the top of the woven words is the Aboriginal name of Country or, specifically, the officially written and recorded name of the Aboriginal First Peoples of that land. In citing specific names, Baylis acknowledges how these designations can be cause for debate – how these histories are also sometimes ‘suspended’ in the writing and rewriting of Aboriginal history in the present. ‘The naming of things is a synthetic act’, Baylis insists. ‘It’s not nature, it’s synthetic, like the materials I use. I think that’s a really important distinction, because I’m not painting other people’s culture or stories; these are names for things.’

Using bold contrasting colour schemes, the two non-Aboriginal place names play optical tricks on the viewer, with the woven grid-like composition echoing the Glomesh and faux-mesh tile patterning in the Postcard works. Baylis’s use of a bright colour palate is motivated by a queer perspective, which sees colour as celebrating all identifications, equally.

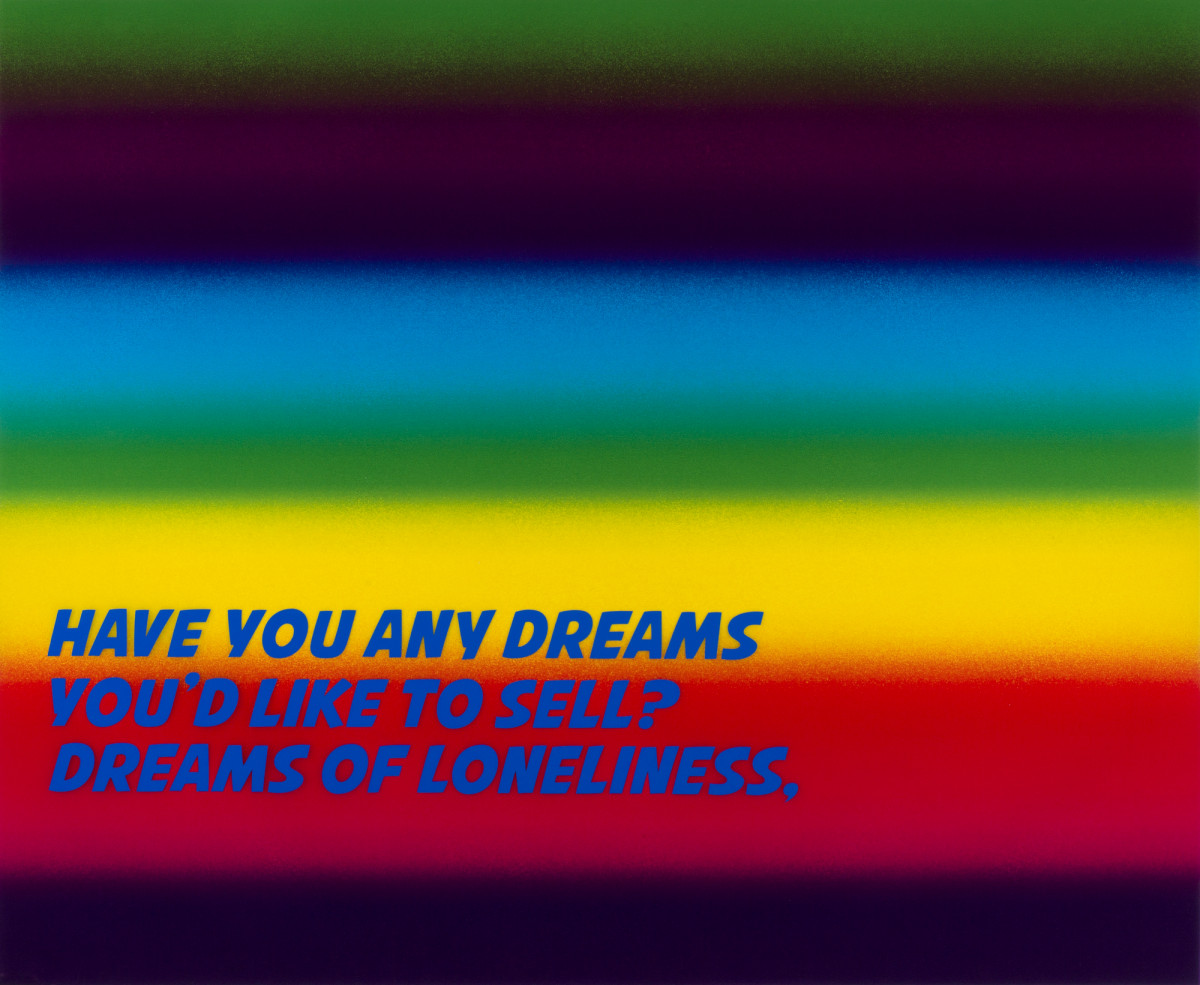

Baylis further weaves into the place-making narrative of this exhibition a queering of the Western pop culture of his time. The series, Tell Them Their Dreaming, playfully cites lyrics from nineteen songs that reference dreams and dreaming. It also riffs on a quote from the film The Castle (1997), which has been affectionately absorbed into the Australian vernacular. In one scene, Darryl Kerrigan (Michael Caton) says, ‘tell him he’s dreaming’ (roughly translating as what to tell the Trading Post seller who is overpricing his wares). Adapting this line in a deliberate act of wordplay to Tell Them Their Dreaming, Baylis presents a visual mix-tape, one that samples diverse styles of music, from gay icons like Kylie and Mariah, to Aussie bands like Sydney’s Ratcat and Adelaide’s The Masters Apprentices.

Each part in this series of small collages uses plastic-coated paper found during his travels in Germany. Conceived in a semi-sleep state, Baylis’s work makes a link between ideas of dreaming as they relate to sleep and the subconscious mind; its application as fantasy and desire in lines from songs; and, most importantly, sacred forms of Aboriginal cultural knowledge called The Dreaming. Multicoloured gradient patterns form a swirling cosmic plane for each work, overlaid with the select song lyrics in mass-produced fonts. The graphic quality of each font and the off-kilter layout create a curious disjunction between text and its application as image. Drawing on the skills of his brother, Ash Baylis, who operates a sticker business in Brisbane, Baylis transforms the paper into unique die-cut stickers, which are placed in custom metallic frames that suggest for Baylis, ‘a monochromatic rock and roll look’.

While Baylis is making a direct link to the countercultural work of Japanese master printmaker Ay-O, much closer to home is his conjuring of the spirit of David McDiarmid’s iconic Rainbow Aphorism, 1994. With this series, McDiarmid applies his trademark wit to a set of queer statements designed in the tradition of political posters or the postmodern text art made famous by Barbara Kruger or AIDS activist collectives like Gran Fury. McDiarmid’s bold and celebratory declarations are a queer manifesto for an age marked by the trauma of AIDS. While McDiarmid’s aphorisms are not necessarily song lyrics like the lines adopted by Baylis, it is worth noting that McDiarmid was renowned amongst his friends for his mix-tapes. At the time he made Rainbow Aphorisms, he dubbed multiple copies of a cassette compilation called Funeral Hits of the 90s, a rainbow gradient adorning the tape’s cover design. McDiarmid’s song selection is likely a soundtrack to the intense frequency of funerals occurring within the gay community at the time.

With Tell Them Their Dreaming, one particular McDiarmid ‘aphorism’ struck Baylis as he conceptualised his own ‘dreamings’: When I Want Your Opinion I’ll Give It To You. If you swap out ‘opinion’, the sentence can take on multiple meanings, depending on its renewed context:

When I want your Culture I’ll give it to you

When I want your Language I’ll give it to you

When I want your Dreaming I’ll give it to you

In his own vivid rainbow-hued dreaming, Baylis acknowledges how The Dreaming does not translate well outside its own cultural experience. ‘I was thinking about how some Aboriginal cultural knowledge and its expression is sometimes hidden, particularly if the work is expressing something secret, sacred, or inherently privileged’, he suggests. Considering that he often speaks and writes in musical song lyrics and is known for his obsessive collecting of popular and non-popular music recordings, there ain’t nobody better than Troy-Anthony Baylis to reconcile Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural sources into his own unique Dreaming Songlines.

Troy-Anthony Baylis, Their Dreaming (Fleetwood Mac), 2019

Troy-Anthony Baylis, Their Dreaming (Fleetwood Mac), 2019Courtesy of the artist

Catalogue essay for Nomenclatures at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 8 August 2020 – 31 January 2021.

Published by Art Gallery of South Australia in 2020.