Tracey Moffatt, Something More, 1989

Tracey Moffatt, Something More, 1989Installation view at Mona

Twenty five years ago Tracey Moffatt’s series Something More (1989) catapulted her into instant art stardom. The first image in the series of nine cibachrome prints is perhaps one of the most iconic photographs by a contemporary Australian artist and is now held in most major public collections, including that of Artbank. To even describe the image—Moffatt in a red dress playing a young aspirational woman from the sticks dreaming of a better life—feels anachronistic considering how widely it has been discussed.

Like most of Moffatt’s subsequent work, Something More deployed narrative conventions appropriated from cinema and popular culture to tell a story drawing from personal experience, but imbued with universal resonances. Indeed Moffatt’s global success could be attributed to the canny way in which she has strategically positioned herself as an artist who refused to be pigeonholed by her Indigeneity, even though it is a strong anchor in much of what she has produced.

Some writings on Something More point out the ‘mixed race’ of the character played by Moffatt; some even going so far as to identify her as ‘Eurasian’, quite possibly because of her tattered red cheongsam. As much as its various racial signifiers are important to the image, it is in the way her work speaks to a universally shared ‘human condition’ that this character comes to stand in for the ‘everyperson’. Most of us would have played that role: poised at a crossroads between where we’ve come from and where we want to be, longing for more. The stylised artifice of these images, now very much a hallmark of her oeuvre, is suggestive of the ‘constructedness’ of identity itself and the way it can shapeshift through masquerade and playacting.

Emerging at the tail end of the twentieth century, amid the heady realm of postmodern culture and identity politics, Something More heralded Moffatt as an artist with a deft ability to appropriate cinema and popular culture and make it entirely her own. Partly drawn from life in its references to her Queensland origins, Moffatt conjures the steamy cliches of 1950s Southern American pulp fiction. In a 1999 interview with curator Marta Gili, Moffatt reflected: “My work has an uncool emotion and heat to it, my narratives have glaring clichéd aspects. People feel that they’ve seen it before—but I’m giving it to them all over again with my slant on it. People recognise the ‘clichés’ and don’t seem to mind them.”

It’s easy to recognise the impact of Moffatt’s work in that of other artists. Australian artists including Christian Thompson and Tim Silver have appropriated Moffatt quite directly, yet arguably it is the ‘clichés’ or better yet, stereotypes of her work that makes it far-reaching and accessible for broad audiences. In an essay examining the way whiteness is represented in the black imagination, cultural critic bell hooks argues that stereotypes are “a fantasy, a projection onto the Other that makes them less threatening. Stereotypes abound when there is distance.”

A decade after this series—and with enough distance afforded by wide circulation and reproduction of Something More #1—a surprising appropriation appeared in the music video for white rap star Eminem’s 1999 hit, My Name Is. Standing in for Moffatt, Eminem switched the race and gender roles. By implication Eminem amplified the potential for a ‘white trash’ reading of the work, while also potentially revealing himself as the kind of ‘terrorising figure’ bell hooks targets in her impassioned essay on racism in American life and culture.

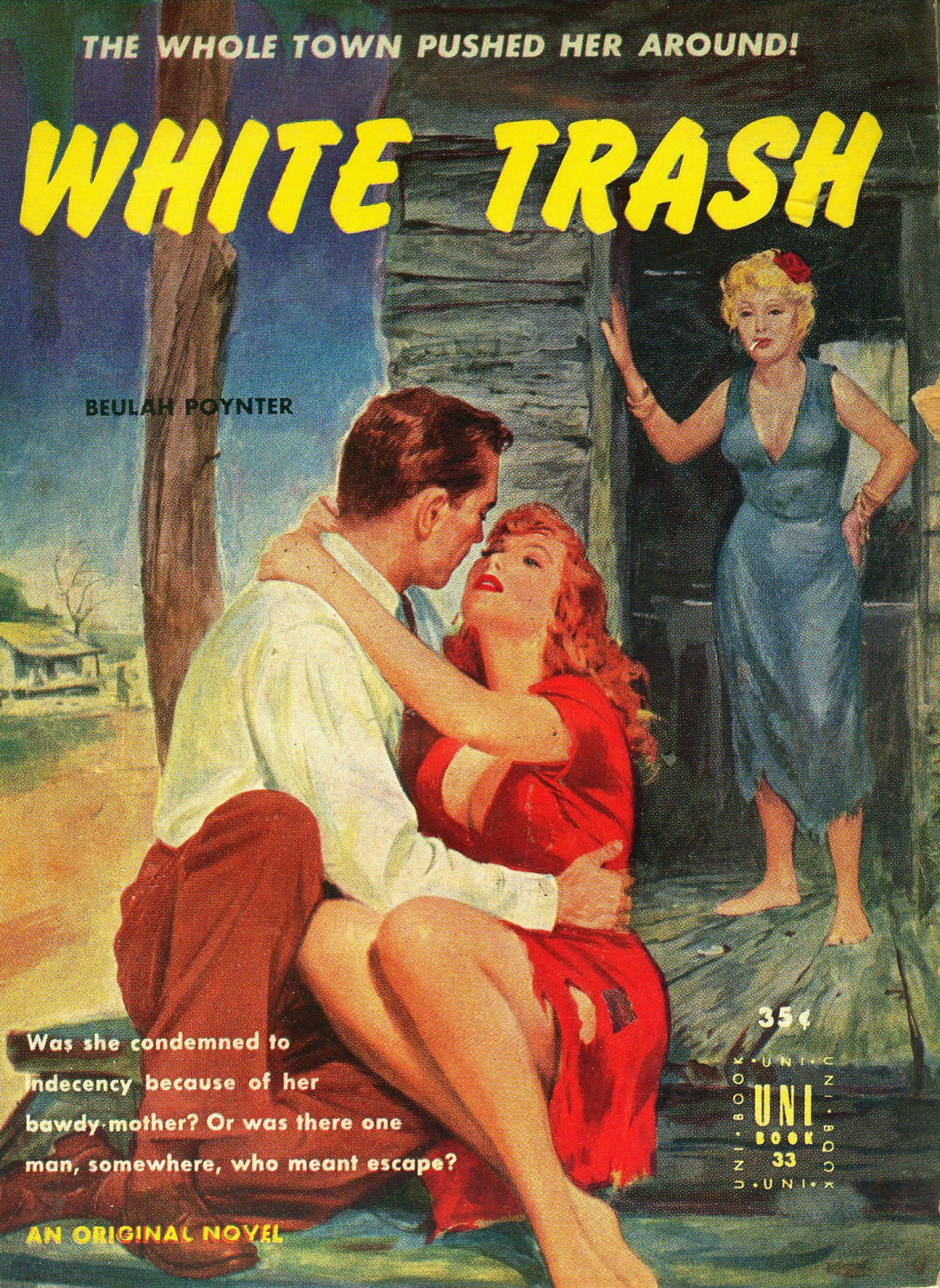

Beulah Poynter, White Trash, 1952

Beulah Poynter, White Trash, 1952Something More clearly mines the stereotypes of trailer park visual culture of pulp classics like White Trash (1952) by Beulah Poynter. The lurid cover artwork of one edition depicts a commonplace trope of pulp imagery, namely the image of an older ‘bawdy’ white mother leaning by the front door. Not quite inside or outside, she is as trapped by her own excess as she is by impoverishment; ironically framed by a door that can be entered or exited at will. Outside her daughter is locked in a melodramatic embrace with her suitor, the tattered red dress speaking volumes about the trouble she’s been in and the trouble for which she is inevitably destined—indeed “The Whole Town Pushed Her Around!”

Post-war American paperbacks like this one were a dime a dozen and “collectively functioned as a vast cultural unconscious”, argues Susan Stryker. “Deposited there were fantasies of fulfillment as well as desperate yearnings, petty betrayals, unrequited passions, and unreasoning violence that troubled the margins of the longed-for world... ‘the stuff dreams are made of ’.” From the ‘cultural unconscious’ to the ‘stuff of dreams’, such images perpetuated, among other things, well-worn stereotypes of white trash identity. As a cultural category, ‘white trash’ is the open secret of whiteness, and it is this visibility and embarrassment that creates a class polarisation between whites.

What does it mean to appropriate an image so heavily steeped in a web of its own appropriations? Evoking Moffatt’s work more clearly than any similar images preceding it, Eminem’s clip complicates how we understand Something More because it situates the work back in direct contact with its pulpy white trash origins. The dominant narratives in Eminem’s music and imagery convey similar tales of poverty and ambition staged in the context of white trash culture. Further complicating these race and class politics, Eminem is typical of an at times awkward ‘white trash’ appropriation of rap, a genre rooted in African American culture. Given Eminem espoused provocative views from this platform, critics have leveled charges of racism, sexism and homophobia against him.

These tensions aside, it is worth noting that Eminem is essentially the product of a ‘black’ record label. As Marcia Dawkins writes: “Eminem ‘repays’ the African American hip-hop community because his sales fuel the success of African American hip-hop mogul Dr Dre’s label, a subsidiary of Interscope Records named Aftermath Records.” (Dr Dre co-directed My Name Is with African American filmmaker Philip Atwell). Whether this is taken into consideration, Eminem’s music abounds with the kind of ‘redneck’ sentiments from which much of the dominant culture would forge some distance. Yet, as a mainstream rap star, he is a cog in the machinery of a still dominant white culture, however ‘black’ the historical origins of rap music may be.

Although framed by the African American tropes of rap, Eminem’s music and videos highlight a continuing fascination with white trash. Gael Sweeney defines white trash as “an aesthetic of the flashy, the inappropriate, the garish... White Trash is the denigrated aesthetic of a people marginalized socially, racially, and culturally. It is an aesthetic of bricolage, of random experimentation with bits and pieces of culture, but especially the out-of-style, the tasteless, the rejects of mainstream society.” In this sense it has all the traits of postmodernism, a golden age of plunder where the original is lost to the copy of the copy of the copy.

Eminem fashioned personas such as ‘Slim Shady’ to create distance from Marshall Mathers—his birth name, hence his ‘real’ self endlessly mythologised by semiautobiographical trailer park narratives. 8 Mile (Curtis Hanson, 2002) starred Eminem in his acting debut as a young white rapper whose own ‘something more’ moment is to transcend his white trash origins. In doing so his whiteness becomes all the more visible through a highly gestural performance of another culture through rap music. Eminem is an example of a class-anxious “Topdeck” (White Americans who seek to appropriate African American culture), writes Jane Stadler: “In moving into black culture, the Topdeck gives up his or her unlabeled position as a normative white subject and is exposed as a racial entity.”

After Eminem’s My Name Is video was released, Moffatt allegedly filed a lawsuit against Eminem’s record company. (As a side note, Eminem’s mother Debbie Mathers filed a ten million dollar suit for slanderous lyrics in the same song, which are incidentally heard during the brief scene appropriating Moffatt’s image.) In short: Beulah Poynter’s 1952 book cover—with its blowsy mum protesting a rebellious daughter’s lust—morphed years later into Moffatt’s 1989 version, with revised racial implications set in Australia, only to be cast back into the white trash imagination by Eminem in 1999. Eminem’s whiteness is exposed in My Name Is through the construction of a stereotypical white trash persona, and quite literally, when he stands in for Moffatt’s already racially marked figure.

I recall when I first encountered this music video on late night television at the time it was released. I was stunned to see an image known so well in an Australian contemporary art context now absorbed into the broader Western popular culture from which it drew. In doing so, this obscure appropriation—it hasn’t been acknowledged in the discourse of Moffatt’s work—complicates the power relations and identity politics already associated with Something More. Looking at Moffatt’s body of work to date, it is clear how Something More set in chain an ongoing preoccupation with aestheticising the power relations between self and other in relation to race and class—albeit often filtered through allusions to the American South, where white trash culture proliferates.

From Something More to Laudanum (1999), Invocations (2000), Plantation (2010) and her video montage collaboration with Gary Hillberg, Other (2010), the relationship of self to other manifests within often hermetically sealed environments thick with claustrophobia and which inevitably erupt as desire turns into madness and hysteria. Remote colonial homesteads; steamy southern swamplands of the south; the tropics of Far North Queensland—such sites are part of the imaginary of otherness. For Moffatt they are one and the same.

It is as if Moffatt reaches to her own localised Australian experience, distancing it from the personal through its rich allusions to twentieth century melodrama and pulp. Although she may have played the ‘coloured girl’ in Something More her racial identity was deliberately ambiguous. This seems to be the point of much of her work: the emphasis on persona and masquerade played out in a world theatre allows a certain level of ongoing transformation, as well as passing across identities and identifications.

Essay for Sturgeon.

Published by Sturgeon, issue 3 in 2015.