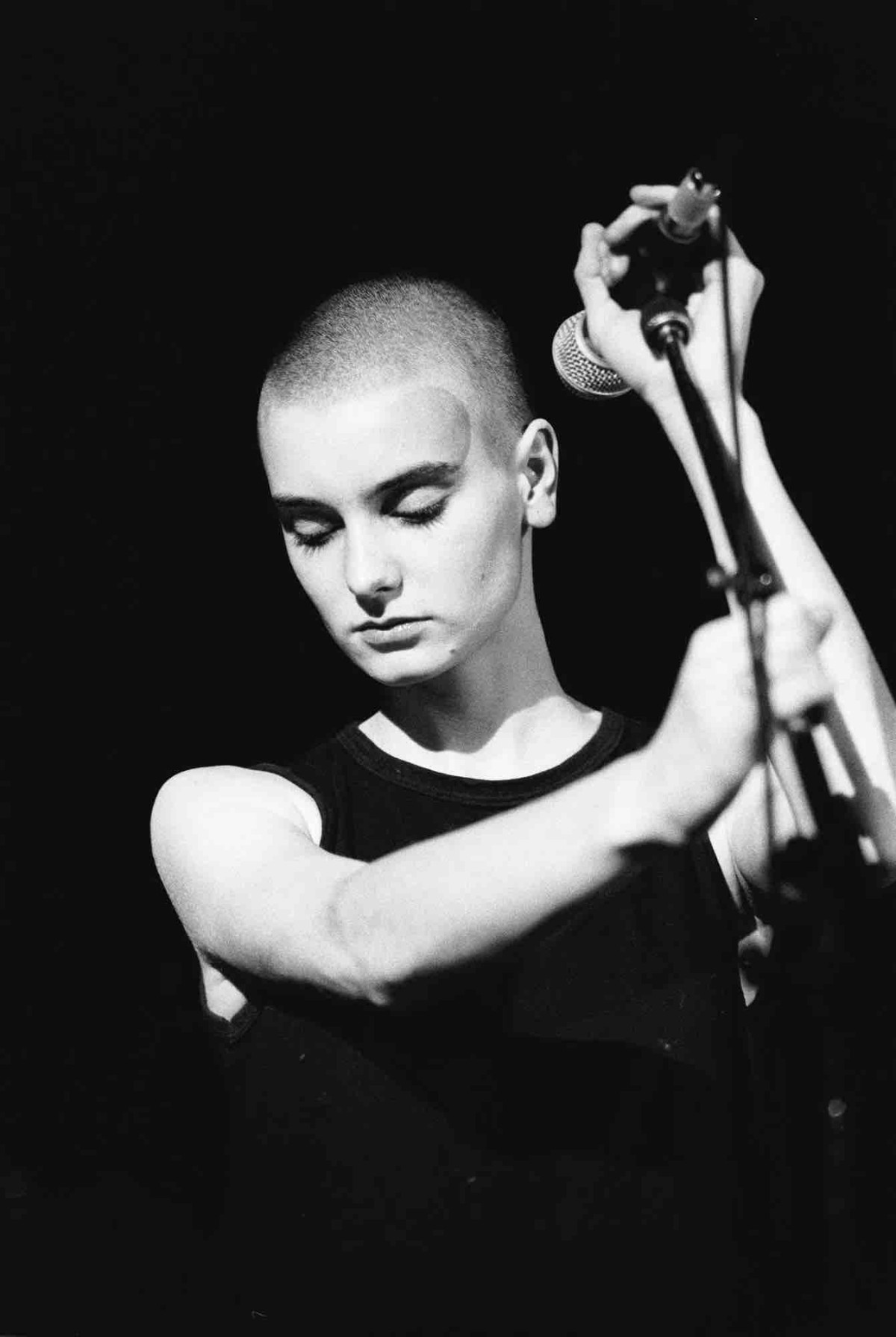

Sinéad O'Connor at Vredenburg, Utrecht, Netherlands, 16 March 1988

Sinéad O'Connor at Vredenburg, Utrecht, Netherlands, 16 March 1988Photo: Frans Schellekens, Getty Images

Who is your celebrity crush?

Are You There? declares all my celebrity crushes: Tina Turner, Cyndi Lauper, Jodie Foster, and more. My practice is like a jukebox of fame fandom, an excuse for an enduring playlist of hits and deep cuts. Tunes to live and die to, as expressed in Funeral Songs (2007–).

Tina Turner died a few weeks before my survey exhibition Are You There? opened at Wollongong Art Gallery in 2023. My own funeral song, Proud Mary, became even more loaded. I dedicated the exhibition as my ‘funeral song’ tribute to Tina.

An event at Wollongong Art Gallery was advertised with a pic of me and Jodie Foster ‘meeting’ in New York in 2001. Jodie has been a lifelong obsession. She has been an enduring subject of my practice, an excuse to publicise my fascination with her since childhood, when she too was merely a child.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Meeting Jodie Foster, 2001

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Meeting Jodie Foster, 2001My ongoing reference to Jodie has also been an opportunity to critically satirise public scrutiny of her once-closeted homosexuality. The obsessive fan trope connects easily with Jodie, given she was the target of a fixated fan, the criminal John Hinckley Jr who, in 1981, notably planned to assassinate Ronald Reagan to get her attention. Hinckley only recently got out of prison for this crime.

That said, I am going to let the celebrity crushes who punctuate my practice speak for themselves. The crush I will discuss is one who has not yet appeared or been indexed by the fandom of my practice. Rather, it’s a ghost crush that now haunts the house, so to speak. It’s a deep crushing love that has informed my life, appearing as a spectral trace, animating my practice and reason for being.

Sinéad O’Connor … more than a crush, I feel a crushing sadness now that she’s gone.

I discovered Sinéad in 1987. Watching late-night Rage on the ABC, the clip for her first hit ‘Mandinka’ (dir John Maybury, 1987) blew my mind. Gave me goosebumps. It somehow ushered 12-year-old me into a post-punk portal that I still inhabit today. All my pocket money went on obsessively collecting singles, albums, posters, t-shirts and magazine clippings. Anything Saint Sinéad said was the Voice of God. A rock star goddess with something to say. A woman whose deeply Irish lineage of intergenerational trauma mirrored my own ancestral matrilineal Irish blood.

Inevitably, all my celebrity crushes are inhabited through performance. My earliest musical performance before an audience was in fact a declaration of Sinéad O’Connor–fandom at high school in 1990. (More on that later.)

Sinéad became famous for her cover of Prince's 'Nothing Compares 2 U'. It was the highest-selling song of 1990 and one of the biggest hits of that decade. But with fame came misery. A string of outspoken actions led to widespread public ridicule and brutal punishment. Sinéad was one of the original twentieth-century victims of cancel culture before we even called it that.

The main event to trigger her infamy was ‘The Pope Incident’: on a live broadcast of Saturday Night Live on 3 October 1992, she ripped up a photograph of Pope John Paul II, stolen years earlier from her dead mother’s bedroom wall. She sang an acapella rendition of Bob Marley’s ‘War’, ending with the call to arms—‘FIGHT THE REAL ENEMY’—as pieces of the picture fell to the floor. A completely punk gesture performed to a gobsmacked global audience, her protest was like radical performance art erupting on TV.

THE REVOLUTION WILL BE TELEVISED.

This act was her takedown of the Catholic Church for failing to confront child sexual abuse perpetrated by Catholic priests. A takedown that misfired and was directed back at her, the consequences lasting the rest of her life. Even despite the same Pope publicly apologising for this very fact nine years later. No apologies to Sinéad, however.

Sinéad famously covered Nirvana’s ‘No Apologies’ in 1994 on Universal Mother—an album created by an artist, a woman, a mother who had been universally obliterated by the world. Sinéad’s fame and notoriety, her honesty and truth-telling, made her a target of universal ridicule and disgust.

On 10 June 1993, Sinéad published an open letter in The Irish Times. In it, she appeals to the world to stop treating her like dirt. She speaks to the grief felt for her abused and lost childhood. She speaks to the way fame screwed her up. ‘It’s an accident I got famous,’ she writes. ‘I have become very self-conscious and frightened as a result of being famous. One doesn’t see oneself reflected in the mirror.’

Months after Sinéad’s open letter, I was in first year at art school and seeking ways to confront my own conflicted-conservative-churchgoing childhood. Eighteen years old, no longer a child but on the threshold of future adulthood, I was searching for my own mirrored ‘true reflection’. One that I could inhabit and perform, one that could transcend. This is how my performance piece Gender is a Drag (1993) came about. Sitting in an open closet and performing to the window like it’s a mirror, I shaved my head as a punk gesture embracing queerness. A coming out performance. A public head-shaving as a political action for personal reasons.

At the beginning of her career in 1987, Sinéad shaved her head in retaliation to music industry executives for pressuring her to be ‘more feminine’ to sell records. For her, it was a middle finger to the record company. For me, it was just one of those art school retaliations to everything. Even though Sinéad’s punk style instantly resonated with a generation set on defying gender norms and societal beauty standards, the irony is that she became famous anyway, an almost overnight mainstream success. Later, she revealed that the darker story behind her shaved head was to not appear pretty, which she equated with her own past experiences of sexual abuse.

In 2013, I restaged my head-shaving performance, 20 years after that self-defining act of coming out. But tragically, on 25 August 2013, my younger brother Christopher died at the age of 34 from an accidental drug overdose. The pre-planned re-staging of Gender is a Drag took place 19 days later, on 13 September 2013. As a result of this family tragedy, the head-shaving became a ritual to honour my deceased brother—a public expression of private grief; an open letter to Christopher.

If that’s what was happening in my world, what was Sinéad doing at the time? She was writing another open letter, 20 years on from the first, as I was re-enacting a head-shaving work, two decades on.

Sinéad’s 2013 open letter was directed to Miley Cyrus and printed in The Guardian following the release of the video for Miley’s ‘Wrecking Ball’ (dir Terry Richardson, 2013). Claiming to be in the ‘spirit of motherliness and with love’, Sinéad wrote that she was ‘extremely concerned […] that those around you have led you to believe, or encouraged you in your own belief, that it is in any way “cool” to be naked and licking sledgehammers in your videos’ after Miley compared her look in ‘Wrecking Ball’ to how Sinéad appears in the ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ video. It came at a time in Sinéad’s career that she routinely spoke out about the exploitation of women in the music industry. She continues:

You said in Rolling Stone that your look is based on mine. The look I chose, I chose on purpose at a time when my record company were encouraging me to do what you have done. I felt I would rather be judged on my talent and not my looks.

Remember earlier when I said my earliest musical performance to an audience was a declaration of Sinéad O’Connor–fandom at high school? I was 15, and the event was a music exam where talent was judged, not looks. I studied music at school. I wasn’t very good, but I got decent marks from creating unexpectedly theatrical performances to mask my limited talent at piano, guitar and voice. (Like the time I asked Mum’s opera singer friend to accompany my spirited piano rendition of Kate Bush’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ for the HSC exam.)

In Year 10, my renegade attempt to sing live looked like this …

An instrumental version of Sinéad’s sexually charged song ‘Jump in the River’ was released as a B-side to ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’. (This was after she had released an R-rated version of the song featuring a spoken word piece on sex and trauma by performance artist Karen Finley.) For the music recital, I brought the record to school and whacked it on the classroom turntable. I pinched one of those Voice-of-God megaphones used at school assembly as a microphone. It amplified my wannabe punk energy and the judgy glares of my classmates in equal measure. It’s not like I’d ripped up a picture of the school principal on live TV! But there were some rather suss lyrics about God’s mistake, worm eggs, and blood-soaked fornication. Just another day at school in the suburbs.

This kid meant business. Sound the alarm.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Open Letter to Sinéad, 2023

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Open Letter to Sinéad, 2023Photo: Zan Wimberley

An unrealised performance lecture from September 2023 and published in Are You There? (Brown Paper, November 2024)

Published by Brown Paper in 2024.