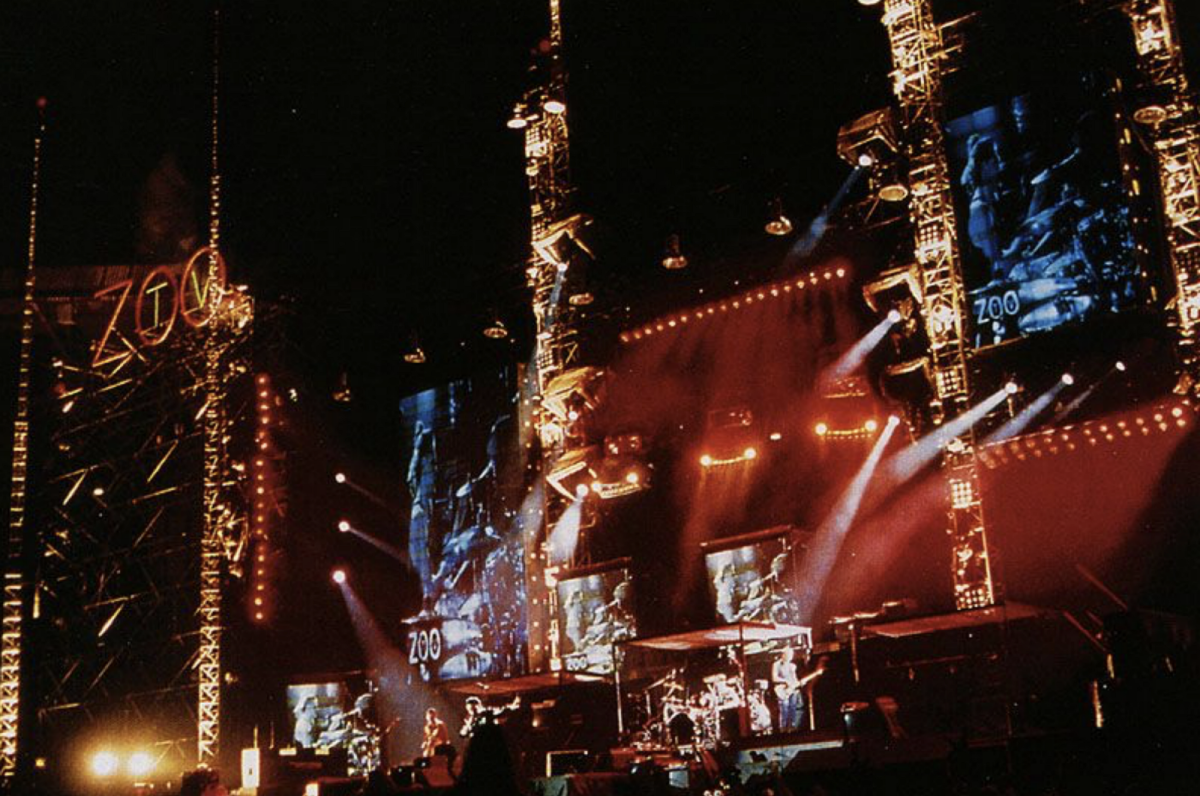

U2, Zoo TV, 1991

U2, Zoo TV, 1991In the time when new media was the big idea

That was the big idea.

— U2, Kite, 2000

When Bono sings this lyric about new media, I can’t help but wonder if “the big idea” is their own use of technology during the nineties when U2 staged the ambitious Zoo TV tour. Bono appears to be using the term “new media” as a convenient moniker for the techno-fetishistic saturation of screen-based media they once employed, as if new media was “the big idea” of the recent past. According to American cultural critics Jack Halberstam and Ira Livingston, “Bono’s various couplings on stage with mirrors, cameras and video equipment fundamentally undermined otherwise stable relationships between fan and star, disconcerting the technology of rock stardom by insisting that the star is the trick of the dazzling lights.”

U2’s song lyric has gained a renewed, somewhat ironic currency in Australia because new media was “the big idea,” until the Australia Council announced in December 2004 their plans to dissolve the New Media Arts Board (NMAB). Without consultation from the industry professionals who were directly impacted, the taskforce conceded that new media was not really an artform. Even though new media and “hybrid” artforms have been thriving in Australia and setting international standards, the Australia Council seemed perpetually confounded by the forever shifting and hybrid character of phenomenon. Positioning new media into a fixed category had become increasingly problematic for the Council because of the way it merges visual art, sound, performance, screen and computer technologies. Perhaps the entangled categorisations were further compounded by the rather tired debate about what exactly differentiates art from design. Whatever the case, the dissolution of the NMAB is a misguided decision considering the field has produced such a dynamic hub of production dedicated precisely to the demystification of and experimentation with technology in cultural settings.

While the dissolution of the NMAB is unfortunate, it really should come as no surprise because cultural practices predicated on hybridity and the blurring of traditional boundaries between art and technology, science and culture, digital and analogue will inevitably become institutional anomalies. Much administrative, institutional rhetoric cannot make sense of hybridity, even though the amorphous shape of visual communication theory and practice is often championed for its ongoing ability to be interdisciplinary. These concepts sound good in theory, but are vulnerable to institutional restructures. How can survival be ensured when by definition, hybrid—the convergence of recognisable or familiar components—resists categorisation. And when traditional categorisations are exploded, or at the very least made hybrid, bureaucracies don’t know how to handle the outfall. Obviously the Australia Council realised about a decade after the fact that they did not really know if new media was a sustainable category.

As a hybrid practice new media is alive and well, but as a category, its hybridity destabilises compartmentalisation. In other words, new media proved itself as a thriving, diverse field of activity, but was too interrelated with other fields that it became an institutional anomaly. Curator Julianne Pierce argues that new media practitioners “challenge the conventions of those practices in order to resist definition or classification.”

The Australia Council crisis has emerged precisely because of the problematic terminology used to demarcate the visual languages of new media. Moreover, the interpretation of new media as a visual language is often uncritically founded on modernist myths of newness. The relevance of anything that keeps calling itself “new” has to be called into question eventually. Can the newness of new media be sustained when new mediums are really just refashioned or repurposed versions of older, more established mediums?

When the Coca-Cola company launched “New Coke” in 1985, the results were spectacularly disastrous — the old Coke was working just fine for soft drink consumers who were not lured by the new version. What this highlights is that newness is often aligned with a product for the sole purpose of marketing. Certainly, the new media moniker has, until now, been an effective means of marketing the “wow factor” of late twentieth-century media technologies. But surely photography and cinema were the new media of the mid-late nineteenth-century, as much as the invention of perspective to render three-dimensional spaces on two-dimensional surfaces was the new media of the Renaissance period.

In her polemical essay “Television Did It First: Ten Myths About New Media” design critic Jessica Helfand states: “Ironically, our dreams of a new hybrid medium are likely to reveal just the opposite: the survival of one medium over the other.”

In their book Remediation, American media theorists Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin argue that the ideologies of newness underpinning new media are based on modernist rhetoric that insists new technologies cannot make significant contributions to culture unless they dispense with the past. Digital media never really break with the formal considerations that structure past technologies; instead they become subject to a process of remediation. Defined as “the formal logic by which new media refashion prior media forms,”

According to Bolter and Grusin, the “double logic of remediation” is set into action by these dual strategies, whereby “[o]ur culture wants both to multiply its media and to erase all traces of mediation: ideally, it wants to erase its media in the very act of multiplying them”.

The photographic slide is an example of a media format that has been subject to intense remediation in digital contexts, even though its formal content (a mounted transparency) is facing obsolescence. For instance, PowerPoint uses the visual language of the slide show, even though it allows the incorporation of text, sound, animation and hyperlinks. Digital thumbnails that direct web users to “go to a larger picture” are often designed to resemble slides, while picture files like the jpeg contain something like a desktop thumbnail to provide instant recognition of the file’s visual contents. PowerPoint’s appeal (especially with marketing experts) relates to the way it prioritises presentation over content and surface over depth, making it the perfect companion to a bullet-point culture weaned on the sensory overload of postmodern media society.

Another part of its appeal stems from the way PowerPoint uses a formal structure dependent on the older, culturally familiar media format of the slide. Released by Microsoft in 1987, PowerPoint is hardly new, but as a digital media application it is certainly newer than the photographic slide. Once regarded as “the big idea,” PowerPoint is now experiencing backlash for its dated graphics and the way its pervasive use in higher education by academics and students is responsible for the “decentring of critical thinking.”

Australian artist Elvis Richardson began the ongoing art project Slide Show Land in 2002. Comprised of more than 30,000 slides bought from eBay, Slide Show Land has been exhibited in New York, Alabama, Sydney, and Christchurch galleries. Multiple slide carousels are installed in the gallery and simultaneously projected onto screens at automatically timed intervals. Additionally, Richardson has experimented with scanning the slides (both transparency and mount) and presenting them on DVD - a strategy of remediation that encourages preservation and expanded viewing potential. Richardson would not necessarily be considered a new media practitioner, but her experiments with blurring the edges of old and new media formats questions the way personal histories are comprehended and maintained when the image rendering technologies used to depict them are made redundant.

It defies logic that new media continues getting away with being called new. Concepts of hybridity and convergence are often synonymous with new media precisely because of the way remediation reveals the process by which old media becomes, not new, but renewed. And as U2 demonstrate in their 2004 iPod campaign, “the new big idea” is how best to brand the ongoing renewal of media forms.

- Jack Halberstam & Ira Livingston, Posthuman Bodies, Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995. p.3.

- Keith Gallasch outlines the debates about new media and the Australia Council in Real Time 66.

- Julianne Pierce, “Battle of the Art Brands,” Photofile 74, Winter 2005. p.45.

- ibid. p.45.

- Jessica Helfand, “Television Did it First: Ten Myths about ‘New’ Media,” Screen: Essays on Graphic Design, New Media, and Visual Culture, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001. p.14.

- Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. 273.

- ibid. p.5.

- ibid. pp.47-48.

- Tara Brabazon, Digital Hemlock: Internet Education and the Poisoning of Teaching. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2002. p.16. For more criticism on PowerPoint see: Edward R. Tufte, The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint, Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press, 2003.

- Daniel Mudie Cunningham, “eBay and the Travelling Museum: Elvis Richardson’s Slide Show Land” in Ken Hillis, Michael Petit and Nathan Epley (eds.) Everyday eBay: Culture, Collecting and Desire. New York & London: Routledge, April 2006.

Essay for Open Manifesto.

Published by Open Manifesto, issue 2 in 2005.