Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land, 2002

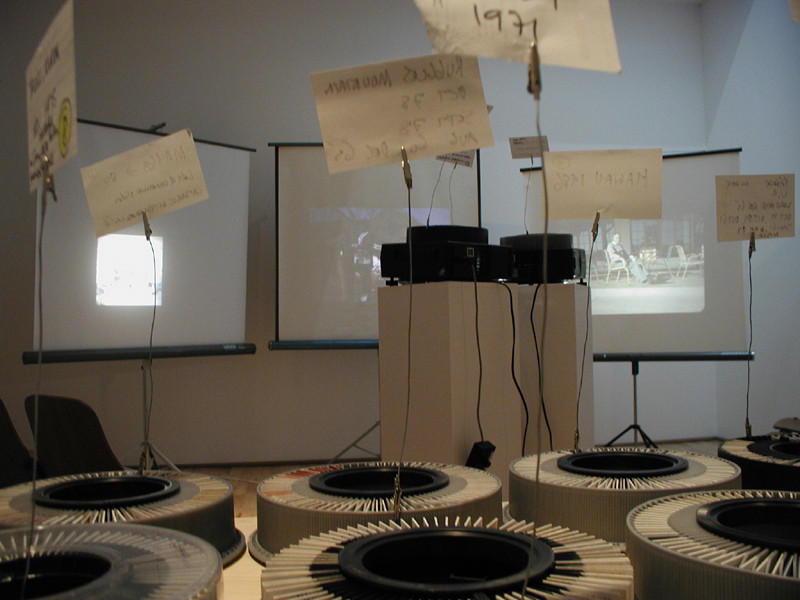

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land, 2002Install view at Room 35, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney

Courtesy of the artist

For inside [the collector] there are spirits, or at least a little genii, which have seen to it that for a collector—and I mean a real collector, a collector as he ought to be—ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects. Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.

— Walter Benjamin

In his essay “Unpacking My Library,” Walter Benjamin invites us to join him in his private library to reflect on what it means to be a book collector. Sitting amidst “the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open, the air saturated with the dust of wood, and the floor covered with torn paper”, Benjamin explains how a collector forms a special relationship with the thing collected. Passionate in his description of beloved volumes, Benjamin reveals that “one of the finest memories of a collector is the moment when he rescued a book to which he might never have given a thought, much less a wishful look, because he found it lonely and abandoned on the market place and bought it to give it its freedom”.

A sense of responsibility informs Benjamin’s understanding of what it means to be a collector, because he or she will invariably act with “the attitude of an heir”. Second hand books—captive, collecting dust, and unread for the longest time in thrift stores and book exchanges—instil such an attitude because they are acquired or inherited with the knowledge that they once formed part of another’s prized collection. According to Benjamin, second hand books are granted new life when collected and a “process of renewal” occurs: “I am not exaggerating when I say that to a true collector the acquisition of an old book is its rebirth”. As the book is renewed it “comes alive in him” in much the same way that the collector comes alive by inhabiting them. In becoming part of a greater collection, the second hand book is reborn bearing its collector’s face and signifying meanings specific to the collector’s cognitive library of memories, emotions, and histories. Benjamin articulates a poetics of memory in collecting: “Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories”. Memory is chaotic because, in addition to being embodied, it lives inside the objects we collect. Changes in meaning occur when those collections (in their entirety or not) appear in the second hand marketplace, and are eventually adopted into a new set of circumstances. Whether public or private, a collection acts as a repository of memory—an exterior mnemonic device—because both the collector and viewer interpret a collection based on their subjective ties to the objects in question.

For Benjamin, the collector is a romantic figure, and justifiably so, considering the care and passion with which he describes a collector’s relationship to the thing collected. The romance of collecting is owed in large part to the role nostalgia and memory play in the shaping of a collection. The urge to collect things from the past often stems from their ties to uniqueness, innocence, and authenticity. Mining the past of its rare treasures allows us to relive a time when life was sweet and unfettered by the soullessness of contemporary capitalism. The phenomenon of eBay reverberates with the sentiments Benjamin expresses in his essay in that eBay acts as a memory machine, where even the most personal items are returned to the second hand market, ready for potential rebirth through new ownership. eBay participates in and actively encourages the chaos of passion and memory, because while pre-loved items will always bear some trace of their previous owner’s identity, the former owner is largely forgotten. All that remains are objects awaiting a “process of renewal.” But, as I will argue throughout this essay, what makes eBay unique as a secondary marketplace is the way it remediates past technologies and secures them in the digital archives of the present.

eBay fosters Benjamin’s poetics of memory through the resale of personal items such as family photographs, especially those reliant on obsolete or fading media formats such as the 35mm slide transparency. In addition to preserving the representational histories and memory imprints embedded in photographic images, a collector of slide photographs safeguards a medium fast becoming redundant. Photographic slide shows, like Benjamin’s unpacked library, are archives of memory supported by their owners’ urge to tell the stories of their lives to others. But what happens when a slide collection’s owner discards these personal histories in eBay’s second hand marketplace? In 2002 Australian artist Elvis Richardson began Slide Show Land, an ongoing art project comprised of slides bought through eBay. These private, amateur snapshots of travel, family life, landscapes, and architecture reveal family dynamics now severed from the referent of their originating source. A window revealing past customs, conventions and ideologies, the slides are “renewed” by Richardson, their adoptive collector. Imprinting her own subjectivity and history on these found objects of “human ephemera,”

By performing a close reading of Slide Show Land, and the way eBay users discard evidence of personal histories at auction, I will investigate eBay to articulate the ways in which it raises questions about the value (or non-value) of personal history in relation to slide photography. Are such histories too difficult to preserve, comprehend and maintain, once formats such as the slide are rendered redundant? How is history, as a representation of memory and perception, discarded or reformatted once a media format becomes an outmoded technology?

Having amassed a collection of more than 30,000 slides, Richardson has exhibited her travelling slide museum in New York, Alabama, Sydney, and Christchurch galleries.

Situated on each carousel is a tag indicating the geographic source of the collection and its eBay purchase value. Richardson has paid as little as two USD for such slides, and in one instance, purchased a collection of 2,500 slides from an amateur photographer in California for sixty-seven USD. Dealers from secondary markets rather than the photographers themselves list many of the slides on eBay because they often derive from deceased estates. This fuels Richardson’s adoptive desire to rescue these abandoned collections of “vernacular” photography from the dustbin of history and honor their origins by sequencing them in the order in which they were taken.

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land, 2002

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land, 2002Courtesy of the artist

I first encountered Slide Show Land in 2002, when it was installed at Room 35, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney, and was struck by the wonder it instilled, a wonder in keeping with Stephen Greenblatt’s definition: “the power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted exaltation.”

The slides are also unique because, unlike the infinitely reproducible nature of photographs printed from negatives, or the images on eBay produced with digital technology, slide transparencies are part of an original positive strip of film cut apart and placed in cardboard or plastic mounts. They are irreplaceable once damaged or lost. Although transparencies can be duplicated or used to print conventional photographs, they are touched by their owners’ hands and retain an aura and authenticity. Benjamin notes that daguerreotypes require “proper light,” are “one of a kind” and “kept in a case like jewellery.”

The uniqueness of the slides Richardson collects makes them apt art objects because one of the prevailing myths about art (especially “masterpieces”) is that their visual power derives from their uniqueness and authenticity. Greenblatt argues that when displayed in museums, masterpieces possess “the power to arouse wonder, and that power, in the dominant aesthetic ideology of the West, has been infused into it by the creative genius of the artist.”

Ironically, masterpieces from an official history of art are often viewed through the slide format in the pedagogical contexts of museum studies and art history.

Richardson’s work also reveals how personal histories become difficult to preserve, comprehend and maintain once the slide format becomes redundant. By performing a rescue mission on anonymous private histories that may have never again seen the light of day, Richardson demonstrates how it is not only certain media formats that face extinction, but personal history itself. When a house is burning, family photographs are the first thing rescued after people and pets. But the growing market for slides on eBay and other second hand markets illustrates how some media formats do not take kindly to posterity. Photographs may be passed down through generations of families, but slides seem to be treated as easily discarded anomalies.

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land 1948, 2002

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land 1948, 2002Courtesy of the artist

Earlier I noted that many of the slides available on eBay derive from deceased estates auctioned by secondary dealer markets. Slides, it seems, die along with their owners. Perhaps they become too onerous to view when the appropriate technology of the projector becomes scarce. Like LPs rendered unplayable when a turntable is discarded or breaks, a slide is often severed from the nostalgic gravity of private history because it relies so heavily on specific viewing conditions. While daguerreotypes may also be “one of a kind” or subject to viewing in “proper light,” their historical, cultural and aesthetic value is assured by their close ties to early photography. Less glamorous in this respect, slides cannot be displayed permanently without a projector, yet to keep a projector switched on for an indefinite time period risks damaging the transparency. A format deemed unviable for long-term preservation, the slide passes away, redundant as a technology, deleted from cultural memory.

A deceased technology once popular with generations of families also now deceased, the slide says much about the way the photograph is inextricably linked to death. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes explores the relationship of photography to death and refers to the punctum of a photo—a minor detail in the image, “that accident which pricks me”—as capable of transforming the reading of a photographic image.

The images in Slide Show Land enact the notion of “time as punctum” not only because they refer to representations of people who are dead or going to die, but because the format of the slide is itself subject to a similar process of erasure.

While Barthes uses historical photographs to illustrate “time as punctum,” there are resonances of this notion with the way eBay listings work. An eBay auction differs from “real world” auction formats largely because the seller decides how long an item will be listed and bidding stops once time has run out. The thrill of eBay derives largely from the urgency of the auction’s looming dead-line. In his memoir on eBay obsession reprinted in this volume William Gibson informs readers that, “with less than an hour to go before the auction closed, I was robotically punching the Netscape Reload button like a bandit-cranking Vegas granny, in case someone outbid me.” An awareness of time and its rapid passing informs users’ responses to eBay, as we see in Gibson’s use of the site to boost his collection of (appropriately enough) rare watches. But what happens to a particular eBay listing? After sixty days it disappears from eBay’s publicly available but temporary archive of recent auctions to make room for new listings. As with much of the rhetoric around the temporal nature of the web, the eBay listing is never meant to be permanent; when browsing through listings, users are aware that the listing (and the page containing it) will soon die. The same “defeat of Time” is an imperative driving the activity of selling and purchasing on eBay, and is made all the more resonant when the images used to illustrate the listing are either collectable historic photographs or photographs reconstructed from dying media formats such as the slide. Two points of finality, then, emerge here: one is the moment the auction ends, and the other is when its listing disappears. If a bidder “wins” the item, that commodity stands in as a record of the auction process—that past event and event passed.

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land, 2002

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land, 2002Install view at Monash Univeristy Museum of Art, Melbourne

Courtesy of the artist

In 2004 Richardson began experimenting with transferring the slide collections onto DVD to expand their potential to travel beyond the gallery and back into the domestic realm they so insistently represent. Richardson scans the slides individually, including their cardboard mounts, on a flatbed scanner, thereby emphasizing the material and physical authenticity of the slide format. Ironically, the artist’s original intention to preserve the nostalgic storytelling performance of the slide show is lost or perhaps remediated. In their book Remediation, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin argue that the ideologies of “newness” that underpin new media are based on modernist rhetoric that insists new technologies cannot make significant contributions to culture unless they dispense with the past. Digital media never really break with the formal considerations that structure past technologies; instead they become subject to a process of remediation. Defined as “the formal logic by which new media refashion prior media forms,”

By being digitally reformatted and presented on DVD, Richardson’s slides undergo a process of remediation that shows how new digital media cannot entirely be divorced from the formal language of past media. When viewed on a television screen, Richardson’s slides are no longer projected onto a white screen where particles of light and dust unite with the whirring, hypnotic rhythm of the clunky slide projector. With the slides reformatted onto DVD, the artist, rather than a viewer who might feel compelled to linger over some images longer than others, now determines the timing of the sequence. More importantly, the slide image becomes documented twofold. As scanned “documents” of discarded family “documentation,” the slides become museum-like specimens to be contemplated in the frame of their seemingly peripheral mounts. In its tactile state, the mount originally was a functional means of framing the slide, making it compatible with the slide tray, including Kodak’s carousel. Once scanned however, the mount is “photographed” like the image contained therein and becomes an active part of the overall digital image presented on screen. A viewer is made aware that once digitally reformatted, the analog slide format faces extinction only in the sense that it has become remediated, swallowed whole by digital screen-based technologies in a paradigm shift.

In a similar manner, eBay itself is a site that, through its strategies of display, remediates slide technology. eBay provides several optional means of including an image in a listing. A seller may mount a thumbnail photograph on a listing’s page, elect to include a thumbnail as part of her or his listing’s hyperlink that will be included in the results of a search of eBay listings, or include in the listing a “Picture Gallery” composed of a number of images of the object for sale. These ways of including an image in a listing heighten an item’s visibility when searching, and also demonstrate how digital contexts remediate the slide image. That the formal constraints of the slide endure on eBay is ironic considering the way eBay positions the slide as a “collectable” category due to its status as a dying media format. eBay listings that do not contain a thumbnail in the hyperlink may instead include a camera icon that links to an image of the eBay item. The icon of the camera makes explicit the ties photography has to consumer culture, and the way eBay relies on the photographic as much as Richardson depends on eBay for her photographic practice. eBay’s depiction of the thumbnail (as slide) and camera icon (as link to a photograph) ultimately highlights the way older technologies are remediated through the foregrounding of eBay’s hypermediacy.

eBay sellers’ ability to mount an image “gallery” of a listed object (resonating with a “galleria” of retail outlets) implies that the listed object has an art object’s aura. Of course art is a commodity like any other, but art galleries often deliberately efface art’s relationship to the commodity and enforce an aura of unattainability even when a price list is available upon request. Greenblatt argues that objects in museums especially function in this respect because, unlike eBay, “the treasured object exists not principally to be owned but to be viewed.”

The framing device of the slide mount is a space that encloses representations of histories, memories, customs, and commodities. According to Greenblatt, “the frames that enclose pictures are only the ultimate formal confirmation of the closing of the borders that marks the finishing of a work of art.”

As Benjamin claims, “ownership is the most intimate relationship” a collector has with his or her collections. This intimacy is forged by the amorphous mnemonic characteristics imposed on objects by collectors. But no matter how “anonymous” a collected object such as the slide transparency might be, its familiarity is owed in large part to the way analog media formats are subject not only to Benjamin’s “renewal,” but to the ongoing process of digital remediation performed by eBay. Memory, then, is not only fashioned through the accumulation of objects, but through the refashioning of technologies by which those objects are imaged.

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land 1970, 2002

Elvis Richardson, Slide Show Land 1970, 2002Courtesy of the artist

- Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting,” [1931] Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (London: Fontana, 1992), 69. Additional references cited parenthetically in the text.

- I borrow this phrase from Australian photographer Edwina Richards, whose book People I Don’t Know in Photographs I Took of Something Else reframes her private archive of snapshots by emphasizing “human ephemera: people I didn’t know or hadn’t consciously noticed before, passing through the backgrounds of the hundred of photographs I’d taken over the years” (Sydney: Peninsula Paper, 2002), 2.

- “Alumni Spotlight—An Interview with Australian Artist Elvis Richardson,” (New York: Columbia University, School of the Arts, Visual Arts)

- The collecting of anonymous slides for the purposes of art also informs the work of the Trachtenburg Family Slideshow Players. The self-professed “indie-vaudeville conceptual art-rock pop band,” take slides bought from garage sales and thrift stores and “turn the lives of strangers into pop-rock musical exposés based on the contents of these slide collections.” Cited in CD liner notes, Vintage Slide Collections From Seattle, Vol. 1 (Hoboken, New Jersey: Bar None Records, 2003).

- “Alumni Spotlight.”

- Val Williams defines vernacular photography as found photography that through its use by a new owner has the potential to resist traditional notions of authorship. “Vernacular photography is important,” writes Williams, “because it is open to any kind of interpretation. It can be refashioned, re-imagined, resequenced, made into a multitude of different stories.” Val Williams, “Lost Worlds,” Eye 55 (Spring 2005), 22.

- Stephen Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 42.

- Super 8 film shares an affinity with slide photography because of the way both signify memory. Australian filmmaker Emma Crimmings writes, “For many people, Super 8 film has become synonymous with what they understand to be ‘memory.’ Saturated colours seep into one another, the film’s graininess quivering and accumulating like dust on every frame. [. . .] At a slender 8mm in width, this tiny memory strip stutters through a camera burning everyday life onto emulsion at 24 frames per second.” Emma Crimmings, “Traces: Naomi Bishops & Richard Raber,” in Remembrance + the Moving Image, ed. Ross Gibson (Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Moving Image, 2003), 37.

- Walter Benjamin, “A Small History of Photography,” in One-Way Street and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (London: New Left Books, 1979), 242.

- To date, a specific category for slide photography does not exist on eBay. In an eBay search I conducted on March 17, 2005, most of the posted auctions for slide collections were found in the Collectibles category, and sub-categorized under Photography: Contemporary (1940-Present). How eBay defines “contemporary” remains elusive, as a majority of the photographic items listed were dubbed “vintage” in their sellers’ descriptions.

- Greenblatt, 52.

- Artists also use the slide format to document their work and promote it to galleries. Increasingly, however, digital photographic technologies are eclipsing this practice, contributing to the obsolescence of the slide format.

- A related reason for the decline of slides lies in the proprietary nature of slide technology. While Kodak had competitors none of them had the highly successful and patented carousel. And Kodak charged a small fortune for a slide projector (and replacement light bulbs), which is, technologically, a very straightforward device—thus severely limiting its market to the upper middle-class domestic sphere and the larger institutional market. Unlike the camera, the slide projector never was fully a part of the consumer market place for earlier image rendering technologies.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography [1980], trans. Richard Howard (London: Vintage, 1993), 27.

- Ibid., 96.

- While the slide show is becoming obsolete in analog contexts, it is reformatted in the digital realm by PowerPoint, a program that uses the vocabulary of the slide show and allows for incorporating text, sound, animation, and hyperlinks.

- Elvis Richardson, Artist Website

- Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), 273

- Ibid., 5.

- For a history and discussion of the magic lantern see Joscelyn Godwin, Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man and the Quest for Lost Knowledge (London: Thames and Hudson, 1979).

- Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder,” 52.

- Ibid., 43.

Peer reviewed book chapter for the anthology Everyday eBay: Culture, Collecting, and Desire, edited by Ken Hillis, Michael Petit, Nathan Scott Epley.

Published by Routledge in 2006.