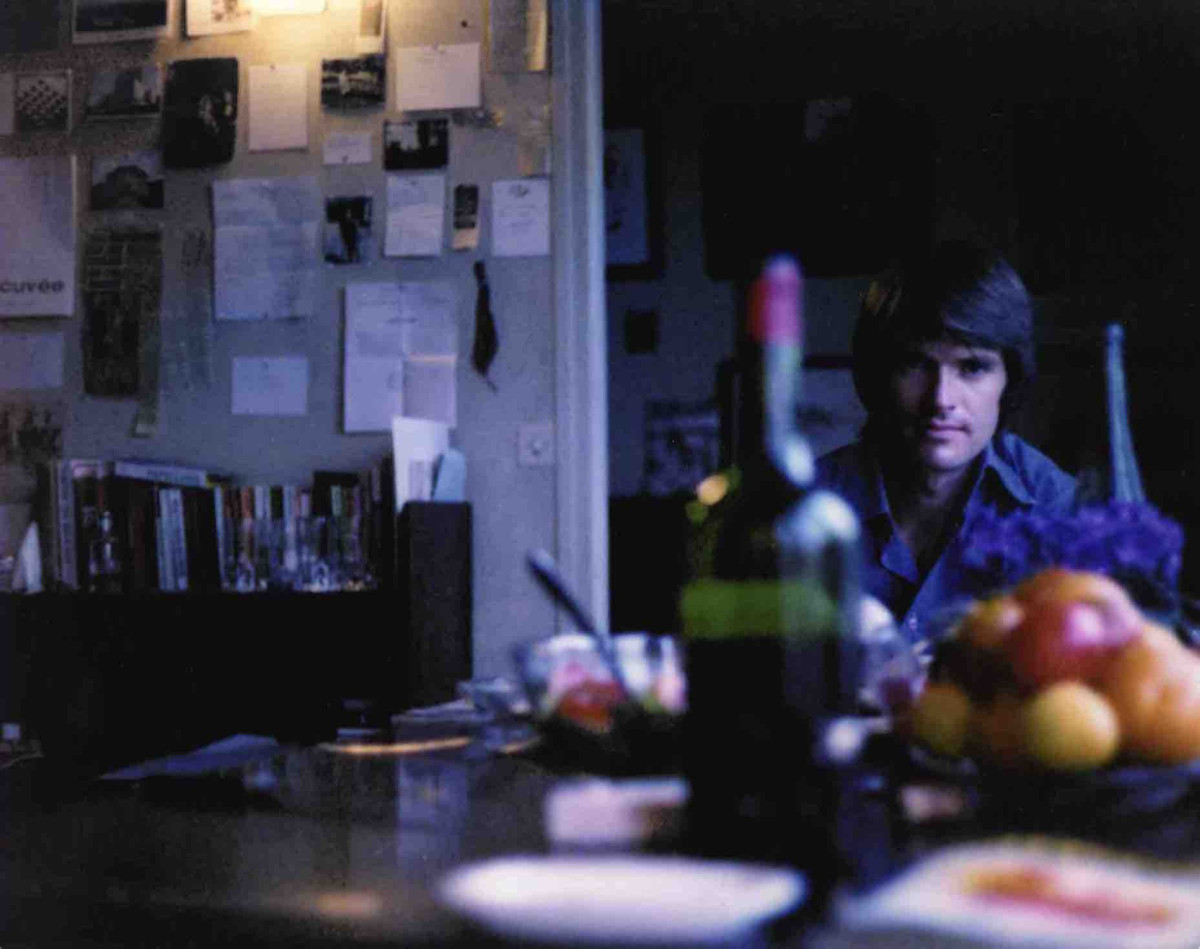

Arthur McIntyre in residence at Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 1975

Arthur McIntyre in residence at Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 1975It is always the same old battle with coming to terms with one’s essential aloneness in this life – nothing can change the aloneness – exotic places and people, or frenetic outbursts of energy, only serve the purpose of taking one’s mind off the aloneness – they do not eradicate the condition. Feeling lonely is something else again, but the feeling fluctuates and is often even enjoyable in a melancholic, perverse sort of way.

Paris is running to stand still. Steeped in a rich history of antiquity, grand tradition and class obsession, it is a city that elegantly negotiates its relationship to modernity and innovation as much as it remains rooted in its glorious past. Paris cultivates its connotations of romance and wonder by bedevilling our ocular sense through a dizzying parade of iconic art, architecture, literature and cinema. Paris is always cast historically as a beacon of cultural significance, as if carried by Nadar’s hot-air balloon from yesterday’s epoch to tomorrow’s Zeitgeist. Casting sweeping historic clichés aside, it can be as bleak and depressing as anywhere else in the world.

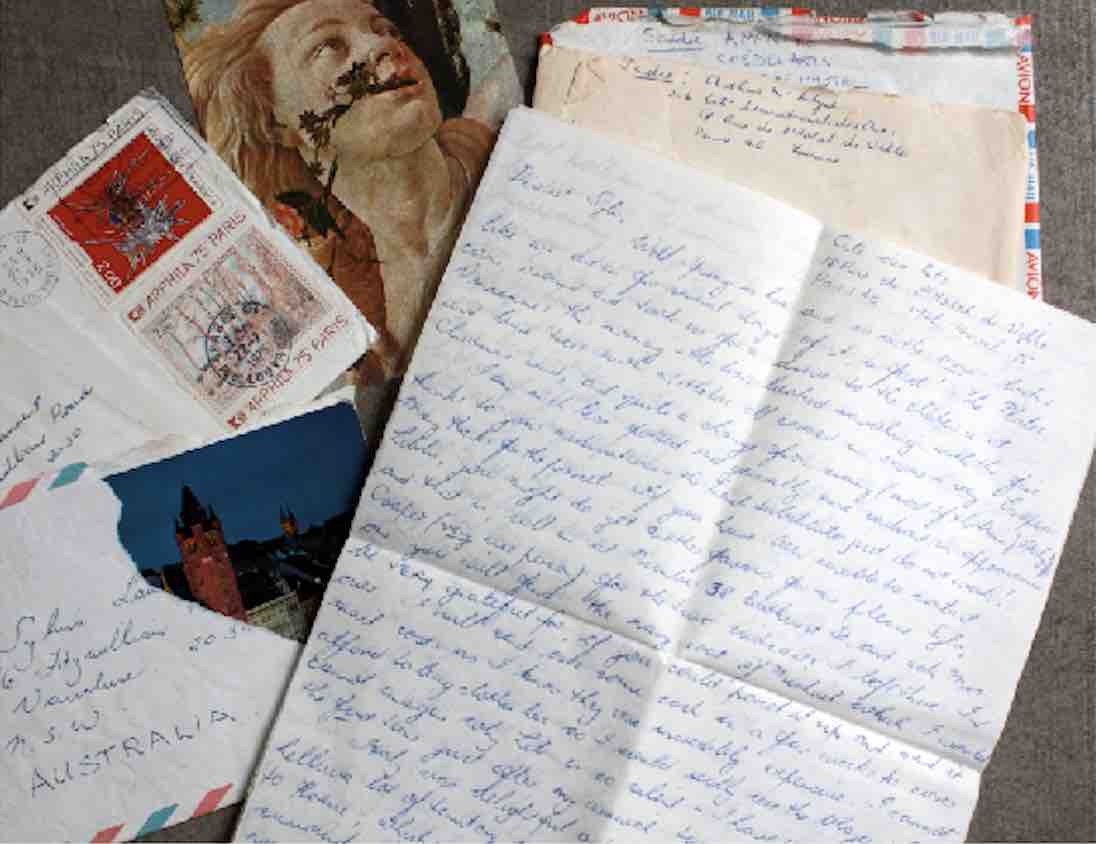

Arthur McIntyre was lured by Paris’s cultural promise, spending most of 1975 undertaking an extended residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts studios through the Power Institute at the University of Sydney. Many Australian artists have occupied these studios and continue to do so today. Walls don’t talk but certainly diaries and letters tell stories that invariably lay bare the lives artists lead – the successes that sing, the failures that sting. The surviving diary McIntyre kept of his time in Paris is a fascinating collection of letters he sent to life-long friend Sylvia Laurent, a now-retired schoolteacher living in Sydney. Like any good travel diary, McIntyre’s letters are imbued with deliciously bitchy commentary, unashamed self-aggrandising, obvious exaggeration, candid reflections on personal relationships and financial woes – all captured against a niggling backdrop of depression and loneliness exacerbated by bleak weather and stemming from the inherited bipolar disorder McIntyre suffered from throughout his life: ‘Sometimes my sense of alienation is simply made worse when I am in unfamiliar places.’

McIntyre was an Australian artist, critic and educator whose achievements were mostly overlooked during his lifetime. As an emerging artist in the 1970s, he made a minor impact with paintings and collages that dealt with the competing duality of survival and disintegration that animates the human condition. Though he maintained a prolific output and exhibition history over the subsequent two decades, his legacy quickly faded into obscurity after his death in 2003. Arthur McIntyre: Bad Blood 1960–2000 was a two-part survey I curated for Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Macquarie University Art Gallery in 2010, which proposed a reassessment of his contribution to Australian art history. Over both Sydney venues was a selection of more than 100 works that plotted key stylistic shifts within his extensive oeuvre.

Arthur McIntyre, Wide Slide, 1974

Arthur McIntyre, Wide Slide, 1974Collection: J. W. Power Collection, Museum of Contemporary Art

Though some early 1960s works were included, Bad Blood mostly comprised work dating from the 1970s onward, reflecting the time McIntyre came to public prominence. In many ways 1975 was McIntyre’s watershed year – where what unfolded would inform his practice for years to come. After completing his education in 1966 at the Alexander Mackie Teachers College/National Art School, McIntyre taught art at various Sydney high schools until late 1974. Just after his January departure for Paris his solo exhibition Slide Series, ’75 was held at Holdsworth Galleries in Sydney. With its muted earthy tones, Slide Series is indicative of McIntyre’s formal exercises in painterly gestural abstraction. Wrote W. E. Pidgeon in the Sunday Telegraph: ‘Arthur McIntyre, a stark black, brown and white action man, views the world as slithery outpourings or eruptions of incandescence over the darkness of chaos.’

Being awarded the Paris residency enabled McIntyre’s leap to full-time status as an artist, a transition greeted with both enthusiasm and anxiety: ‘I get overcome with stupid guilt feelings every day [that] I do not manage to complete or at least initiate some new piece of work. I suffer from an awful inability to relax – the old brain ticks away all night now as well as all day.’

From Paris McIntyre visited Venice, Florence, Stockholm, Basel and London and these travels influenced his approach to making art. Due to the financial and logistical constraints of working abroad and sending work back to Sydney for exhibition, McIntyre worked on a smaller travel-friendly scale and more on paper than canvas or board. Collage became a primary medium, especially in response to his view of Paris as a decaying city, textured by peeling layers of transition between its past and present. These ideas were contextualised by McIntyre when interviewed for an art magazine: ‘Somehow Paris itself seemed to me like a collage. Everywhere I looked there was decay and mildew and it was the middle of winter and there were posters peeling off walls. Paris was made up of layer upon layer of textures which symbolised various histories and changes which had taken place.’

Even though McIntyre had used collage before this point, it is possible that Carl Plate, who was living in Paris at the time, also influenced McIntyre’s principal focus on this medium. Plate was making many of his linear multiple-strip collages, which were collectively shown for the first time in the exhibition Carl Plate: Collage 1938–1976 at Hazelhurst Regional Gallery in 2009. In a tribute written for the journal Aspect: Art and Literature after Plate’s death, McIntyre writes:

In 1968, [Plate] was the first appointee to the Sydney University Power Bequest studio at the Cité Internationale des Arts, in Paris, where he later occupied other studio spaces. On one of these occasions (early 1975), I first encountered Plate, who, although fighting a brave battle with serious illness, still found plenty of time to offer a warm hand of friendship to a young artist slightly overwhelmed by his first experience of life in a strange and often hostile European capital.

In his letters McIntyre describes several soirees he attended with Plate, Stan Rapotec, Charles Blackman and their respective wives. McIntyre reveals that he especially enjoyed, if not preferred, the company of the women. Jocelyn Plate was ‘particularly pleasant and generous’,

Among other artists he befriended in Europe was the late Swedish painter Ulla Waller, who for many years lived in Paris. Ever the cinephile, McIntyre seized the chance in August 1975 to stay at her seventeenth-century Stockholm mansion that had been used as the set of Sidney Lumet’s 1968 film adaptation of Chekhov’s The Seagull: ‘Her daughter is married to Ingmar Bergman’s son, in fact, and, naturally, Ulla is full of wonderful anecdotes and stories about the Swedish film scene.’

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Syphilis, 1975

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Syphilis, 1975Collection: Daniel Mudie Cunningham

The work McIntyre made during 1975 collectively formed the landmark Survival and Decay Series which was exhibited at the Salles Sandoz in the Cité Internationale des Arts in May 1975. The artist’s tendency towards hubris is never more pronounced than in passages about the exhibition planning. Bitter rivalries with co-exhibitors and forced diplomacy with the powerful head of the Cité, Simone Brunau, almost ruined the whole event. A month before it opened, the group of exhibitors expanded from three to ten, with McIntyre petulantly declaring: ‘I will be damned if I will be totally surrounded and swamped by the shit of nine others!’ Eventually it opened on 21 May as the initial three-man affair where, according to McIntyre, ‘I did manage to steal the show … The other painters, both French, have appalling work with a general feeling of having been dipped heavily in “Gravox” – the perfect foil for the starkness and clarity of my work.’

Boldly direct and unsettling in their sporadic use of humour, his collages depicted the dualities of existence – birth and death, light and dark, survival and decay – by juxtaposing erotica and medical images of body parts often ravaged by sexually transmitted diseases. In many ways they pre-empted the AIDS crisis that was about to erupt globally. With or without the onset of AIDS, the collages were well received in Paris, but outraged the public when shown in Sydney in 1976. Nancy Borlase, however, championed them by writing in the Sydney Morning Herald: ‘With the exception of Elwyn Lynn there are few painters here who can extract such passion from the dustbins of life. These spongy metaphors for blemished flesh are chilling reminders of human vulnerability. They belong to a European tradition of morbid curiosity, reflected in Géricault’s corpses, in Rembrandt’s Anatomy lesson, in Alberto Burri’s wounded, stitched and bleeding bags.’

The shadow of death on his work was further compounded by a telegram sent to Paris from his sister Lynne in Sydney, announcing the death of his father. McIntyre’s bitter disregard for his father rings loud and clear as he mentions the news in passing to Laurent, followed with enthusiastic thanks for a previously received parcel of Wella and Savlon (he could never find suitable European alternatives): ‘A million thanks, Sylv – now I am back in filthy old Paris I will really need to use it to help hold the skin on my face together.’

The last of the letters sees McIntyre now in ‘dreary old London town,’

— Till soon, dearest Sylv. – much love, Arth.

Arthur McIntyre's letters from Paris, London and Stockholm, 1975

Arthur McIntyre's letters from Paris, London and Stockholm, 1975- Arthur McIntyre, letter from Paris, 5 May 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter from Paris, 21 July 1975.

- W. E. Pidgeon, ‘Heavyweights’, Sunday Telegraph, 16 February 1975, p. 93.

- Sandra McGrath, ‘The last image is of the bush’, The Australian, 8 February 1975, p. 16.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter from Paris, 14 February 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, ‘F.I.A.C ’75: 2nd Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain Paris at the Pavilion d’Expositions de La Bastille’, Art & Australia, vol. 13, no. 2, Summer 1975, p. 181.

- Arthur McIntyre cited in Bronwyn Watson, ‘Art of Arthur McIntyre – a profile’, Oz Arts, no. 1, 1991, p. 20.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter from Paris, 4 June 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, ‘Carl Plate – a personal tribute’, Aspect: Art and Literature, vol. 4, no. 4, 1980, p. 64.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 22 May 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Stockholm, 7 August 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 12 April 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 22 May 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 4 June 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 7 April 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from London, 30 September 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 22 May 1975.

- Nancy Borlase, ‘Mainstream paintings alive and well’, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 March 1976, p. 7.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from Paris, 18 August 1975.

- Arthur McIntyre, letter to Sylvia Laurent from London, 30 September 1975.

Essay for Art & Australia

Published by Art & Australia, issue 48:4 in 2011.