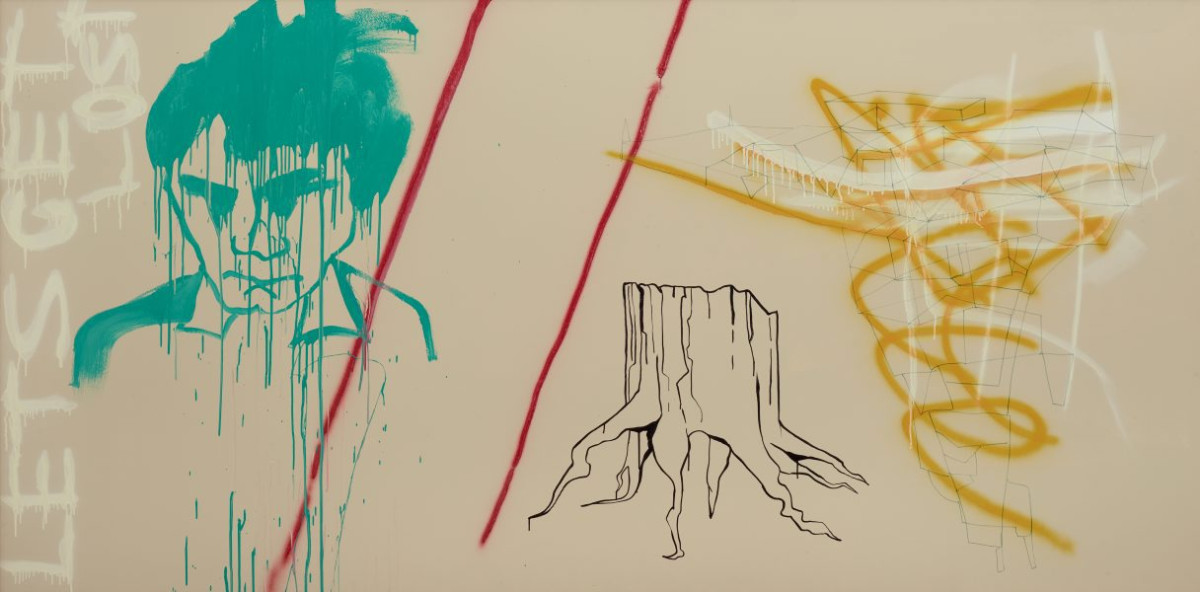

Adam Cullen, Lets get lost, 1999

Adam Cullen, Lets get lost, 1999Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

On 19th December 2005, Adam Cullen and frequent collaborator Cash Brown staged a performance, Home Economics: Weapons of Mass Sedition, to an audience at the Museum of Contemporary Art. It’s only a week after the race riots in Cronulla and barely a month after the Federal Government revealed the Anti-Terrorism Bill that included sedition laws effectively inhibiting artists from expressing political critique or satire in their work. Appropriating the style of a TV cooking show, Adam and Cash demonstrated how homemade bombs are engineered. Using bottles filled with explosive fluids and chemicals, they built the bombs, lit them for a moment, and doused them before risking the explosive demise of the MCA. Afterwards the audience could inspect the bombs as if they were sculptures.

Normally I’d question the authenticity of the explosives, chalking it up to a performative conceit. But having only interviewed Adam five days earlier I’d heard him tell me how he wanted to explode (I’ll get to that later) I found myself sitting scared shitless and realising how appropriate my death might take place in a contemporary art museum. At least my career in the arts had not been in vain…

Five days earlier I’m driving to Adam Cullen’s house. He rings my mobile to say he has to duck down to the shop and I should let myself in and have a look around if I get there before he returns. I arrive, the front door is open, and I let myself in as instructed. Tom Waits is playing, stuffed animals peer at me suspiciously from the walls, and animal skins are strewn casually here and there. Gingerly, I look around, seduced by his art collection and the view of the Blue Mountains rolling beyond the balcony.

Adam returns minutes later, makes me tea, and his mobile rings: the first call of many. Adam explains that he is performing an anti-sedition piece at the MCA, and he has less than a week to get it together. Adam’s mood is a combination of rage and nervous vigour at the Government’s conflation of sedition with terrorism. The phone keeps ringing as news gets around about the performance.

I have barely touched my tea and Adam offers me a Bloody Mary. “Sure,” I say. Adam and I toast to anti-sedition before he shows me a couple of his favourite things. He asks if I have ever shot an air rifle, and when I answer in the negative, he insists on showing me how. Seated at his dining room table, we aim the rifle through the balcony doors at a knotted section of a distant tree. Remarkably I hit the target on my first attempt, perhaps because Adam told me to imagine the target was a politician. “Hunter S. Thompson used to have a great big head of Edgar Hoover he used to fucking shoot all the time,” he says before lodging another pellet in the tree. “I’ve even shot holes in artworks that I didn’t like,” says Adam while loading more pellets.

The air rifle was a gift Adam received when he was ten: “My parents gave it to me for Christmas and half an hour later my father was making a BBQ and my older brother paid me five bucks to shoot my father in the arse from the top storey of the house. He just went, ‘What the fuck was that?’”

My Bloody Mary is half finished now, and I’m feeling less confident that my next hit will be a success. “Imagine it’s an extension of the arms and your eye,” he says when I’m not holding the rifle properly. “Very McLuhan,” I remark. “Sure is,” he agrees. I fire the air rifle and miss the target; the pellet firmly lodging in the doorframe. Unsure whether to be embarrassed, apologetic or just plain scared, I’m relieved when Adam laughs it off saying, “That’s pretty cool. I’m going to leave that there forever.” Adam takes his turn and after three shots, he also misses the tree having coincidentally shot the other side of the doorframe. We just sit there astounded by the symmetry. “You’ve inspired me to shoot holes in my own house,” he says before making another round of drinks and setting down to answer some of my questions.

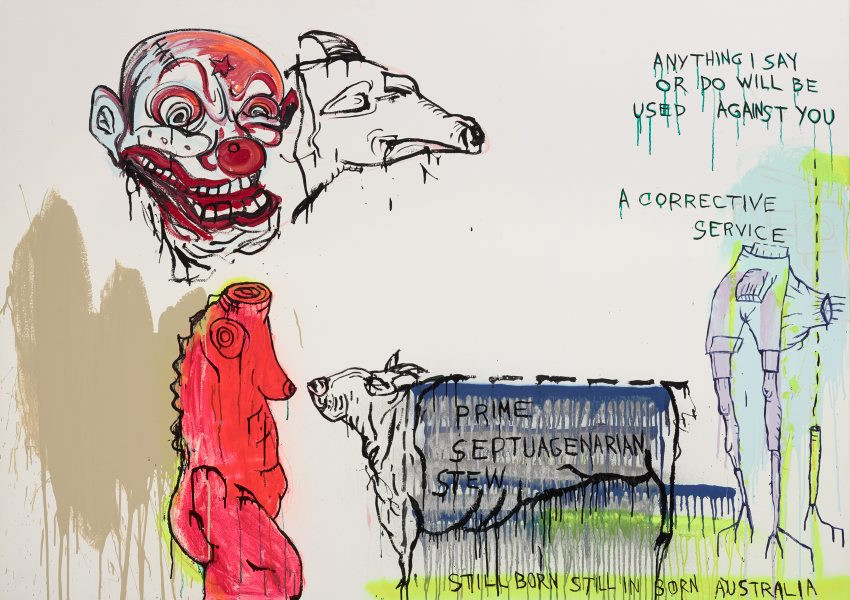

Adam Cullen, Anything I say or do, 2001

Adam Cullen, Anything I say or do, 2001Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

Have you made a bomb before?

Yes, heaps of them. As a kid I used to blow holes in the greens of golf courses. I used to put them in cars in car parks; I used to shred garbage cans. I used to go shooting pigs and would rope them onto the back of wounded wild pigs, light them and watch the pig explode. Actually, it was heaps of fun to be completely surrounded by absolute fucking carnage. These days I just paint pictures.

Do you perform much?

I occasionally do, but I haven’t in awhile. I’m excited about performing at the MCA because I think there is a certain amount of scaredy-catness and absolute gutlessness that comes with these terror tactics the Australian Prime Minister has enforced. I just think that artists are great people who care more than most because we have a sense of aesthetics, which is about ethics. I’m not interested in morals being a lapsed Catholic, but I think that Catholicism gave me a lot of great things like a sense of theatre.

There’s something so inherently Australian about your work, especially the way you to draw upon Australian mythologies and turn them on their head.

I’m with cultural critic McKenzie Wark, who believes Australia is one of the most post-modern countries. I think Australia is very unique and young, uniquely young, and you can’t assume a lot about us. I think we can adapt things faster than most people.

In Ingrid Periz’s monograph on your work, she mentions your reputation as a bad boy of the art scene. Did that come from art school antics?

I was ‘out there’ at art school. It was the mid-eighties, and I wasn’t really liked because there was this thing called feminism. Joan Grounds, who was seen as a girl artist, was my biggest champion. But I suppose that ‘bad boy’ reputation came from the work I was doing at the time, and what I was actually doing outside of my practice. I wasn’t reading things and then sitting down to think about them. I was reading them and fucking doing them. At the time I was reading Nietzsche and exercising that. I was screwing bad people, shooting things, eating bad food, trying to make bombs, reading really obtuse bad literature, or associating with bad people and trying to aestheticise that. I suppose Periz calls me ‘bad’ because I didn’t turn up in nice clothes.

Is that a crime?

Apparently it is. I am with Quentin Crisp who said, “Fashion is for people with no style of their own.”

Critics tend to write about your work and life interchangeably. Why do you think the two become blurred?

Maybe I’m a younger version of Hunter S. Thompson because I have an incredibly inflated sense of mortality. My work tries to describe the end of things, which is sort of the beginning in some way. Full stop. End of fucking story.

How did you feel when Hunter S. Thompson committed suicide?

I just thought, you gutless prick. Yet, when I actually thought about it, I realised it was understandable. If it’s time to go, it’s time. Hunter wanted to explode and that is just the greatest thing. I was awfully saddened when he passed away because I’d actually planned to explode way before him. He said ‘I don’t really want to live in a country where you can’t stand naked on your balcony and shoot guns’ and I totally agree with him. I just think if I could be a little like Hunter or… if everybody could be just a little like Hunter, the world would be a great place.

Will you continue to be a bad boy, even if we live in this repressive culture?

Yeah, that’s why I’m going to do this performance work at the MCA.

Adam Cullen, Residual paroxysm of unspoken and extended closures interrogated by a malady of necrogenic subterfuge with a nice exit, 1993/2008

Adam Cullen, Residual paroxysm of unspoken and extended closures interrogated by a malady of necrogenic subterfuge with a nice exit, 1993/2008Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

We should talk about your so-called grunge period. American artist Mike Kelley is famous for using grungy materials ordinarily representative of low culture and considered unworthy to be seen as art. Themes of low culture have also been attributed to your work.

I certainly think that Kelly helped me to justify things. But I don’t see these things as low quality or as bad. I think that is an ethical choice as opposed to an aesthetic choice. I don’t like being accused of making ugly art. I thought I made nice looking work. I was unemployed at the time, and used materials I could find. I had no access to money.

Why after that period did you focus more on painting?

Purely because I couldn’t afford to make the objects that I wanted to depict. I could paint them faster. But now I’m trying to get into sculpture, film and performance. But painting was a good way to illustrate what I wanted to do.

Do you consider yourself a painter or an artist?

I would rather be called an artist than a painter because I have always adhered to the phrase: ‘as dumb as a painter.’ I entered the Archibald portraiture prize as a fucking gag and after four years of entering I won. I always enter prizes as a gag, not unseriously, but art prizes are a gag. I’m not a painter, I’m an artist and I think there is a hell of a difference. Australian performance artist Mike Parr never ever wanks his crank and shows off how great a draftsman he is, but he can outdraw anyone I know. But he’s an artist first and not a drawer or painter. He taught me that when I was 18 and I just thought, ‘Wow, where have you been all my life.’

Which other artists inspire you?

I was always a big Joseph Beuys and Martin Kippenberger fan. I was never a Damien Hirst fan, ever.

Do you say that because some people compare you to him?

I think that I actually did that kind of work a long time before him, but living here in Australia it wasn’t popularised in the same way. Also I think that he’s such an arrogant prick, but that’s probably what they say about me. I don’t think I am. Anyway, I like Pollock, but my main influence is Goya.

Why do you use criminal figures as source material for your paintings?

I suppose because I’ve always had trouble with understanding the idea of law, and my family and ancestors have always had trouble with authority. We ostracise criminals, making them into an outsider culture, and yet we persecute them under our system. Australia certainly has an interesting criminal past, which contributes to its identity. Australia got the criminals and America got the puritans.

How did you meet Mark ‘Chopper’ Reid?

We met eight years ago through certain friends, but we got close when I painted him for the Archibald and illustrated his book Hooky the Cripple in 2002. We share certain views and the same sense of humour. And it’s odd, he’s often accused of being far right wing, but he’s incredibly far left wing, old-fashioned and Irish Catholic. Just because he’s been suspected of killing a few drug dealers doesn’t mean he’s far right wing. He has never been found guilty.

Six years ago art critic Bruce James wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald that you were “too young to be an old master, too old to be an enfant terrible… he’s between callowness and maturity”. So where are you today?

I’m still too young and I’m still too old. I can’t really grow up because I don’t have any kids yet. Artists don’t have kids, and that’s what artists do best. So I’m probably still an enfant terrible.

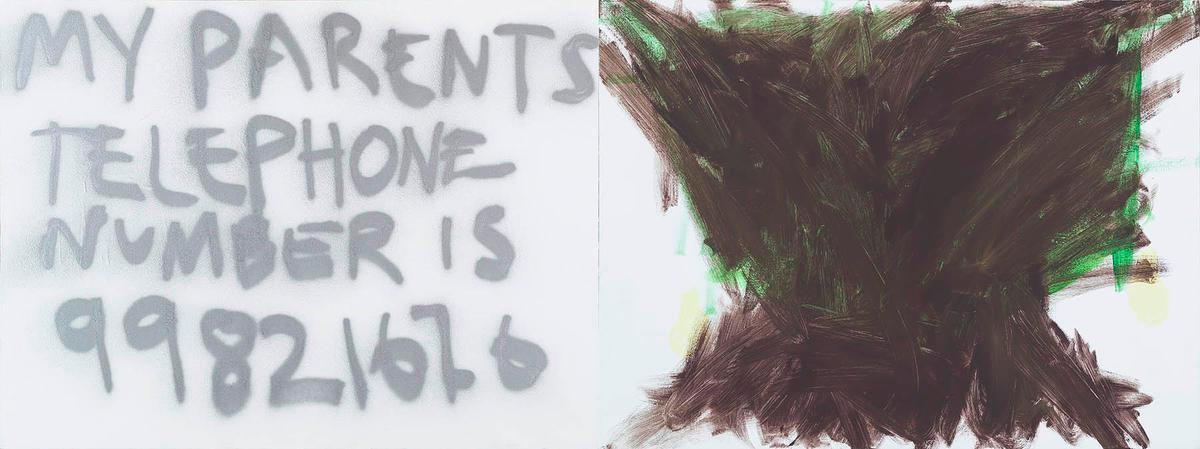

Adam Cullen, My parents' telephone no. is 99821626, 1996

Adam Cullen, My parents' telephone no. is 99821626, 1996Collection: HOTA Gallery

Interview with Adam Cullen, that was later adapted and expanded into the essay 'Special Talent' for Sturgeon in 2015.

Published by Empty, issue 6 in 2006.