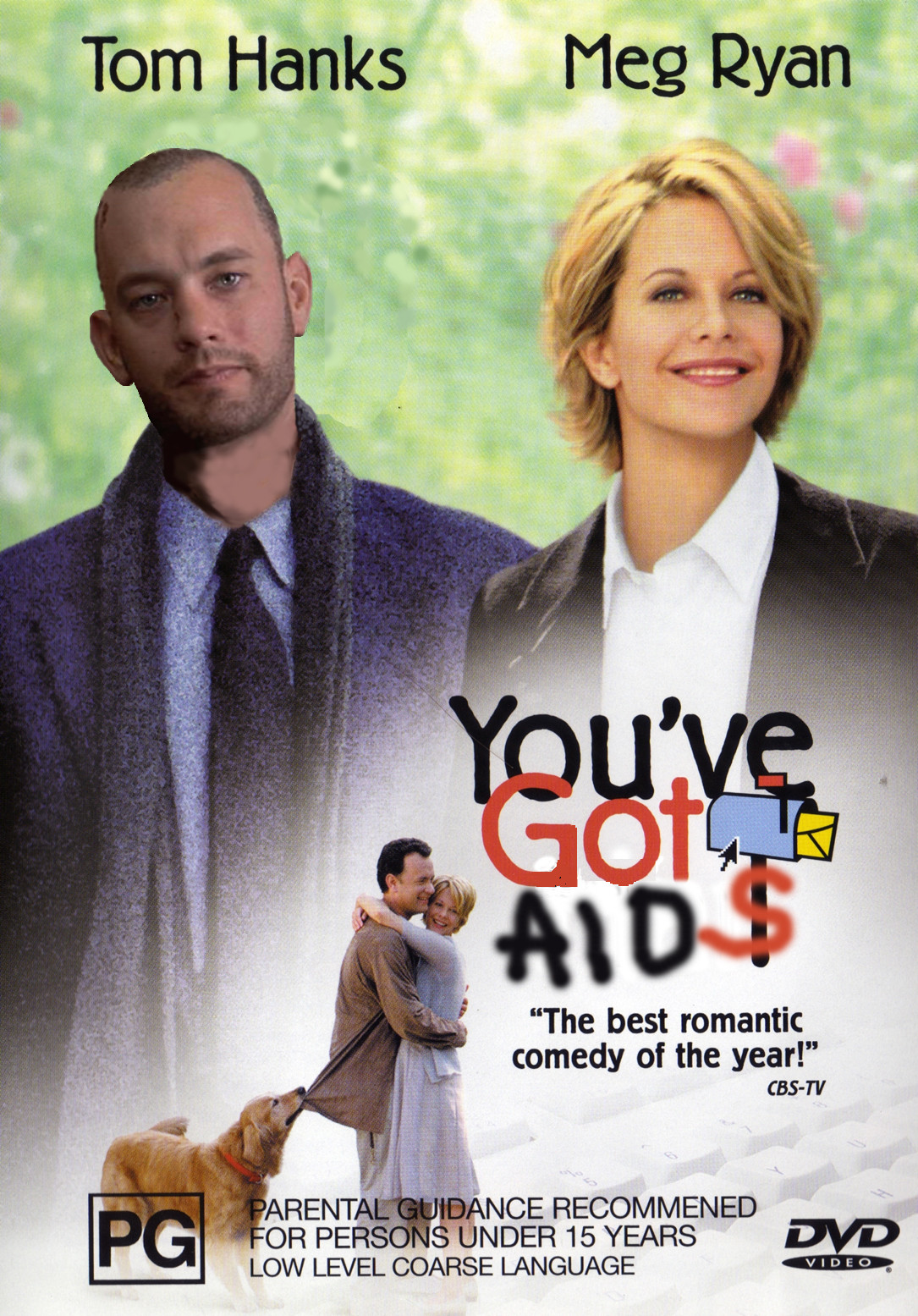

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, You've Got AIDS (Sleepless in Philadelphia), 2007

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, You've Got AIDS (Sleepless in Philadelphia), 2007romance n. 1. a tale depicting heroic or marvelous achievements, colourful events or scenes, chivalrous devotion, unusual, even supernatural experiences or other matters of a kind to appeal to the imagination.

The Macquarie Dictionary provides ten definitions of romance and what unites them mostly is the stress placed on romance as narrative. Characterised as invention, exaggeration, imagination and extravagance, definitions of romance focus on make-believe. Romantic love seems a secondary after-thought for the dictionary, as if real life experiences of romantic love come nowhere near their representational counterpart. This got me thinking that perhaps outside the conventions of narrative and genre, romance does not exist. This maybe explains why romance is so unattainable, at least in lasting measures. Its temporal and transient character is like a swift punch in the guts; plummeted into absolute incoherence, logic breaks down and all that remains is a disorienting and confusing episode that is here today, gone tomorrow. Opening credit sequence for now… end titles later. Romance never lasts because: Romance is representation. Romance is genre. Romance is narrative. Like narrative structure, romance has limited use value in real life.

Browsing through my local Blockbuster, Romance is a category that sits on the other side of the store to Action. I suppose if I had to make a choice, I’d go with the ‘chick flick.’ Trawling through titles in the Romance section, I’m confronted with an idea that romance is conceived of by what it excludes. Romance is the implementation of gender codes, compulsory heterosexuality and a precursor to Family – that mother of all invention. Romance, then, is very Blockbuster in that it competes for the same normative ideological space as Blockbuster, the conservative American franchise which famously discriminates against stocking titles that supposedly undermine good old fashioned Christian ‘family values.’

Romantic fiction is perhaps even more nebulous than a cinema of romance. Romantic literary representations depend on melancholy, pathos and tragedy to extract appropriate emotional responses from a reader. Low culture at best, romance novels are the ‘lowest’ form of fiction and their writers are seen as the ‘lowest’ of all writers. A case in point is the depiction of the romance novelist in Romancing the Stone (Robert Zemeckis, 1984). World famous for her passion pot-boilers, Joan Wilder (Kathleen Turner) writes because she has no romance in her real life. Joan Wilder’s life ain’t that Wild, until of course fiction and reality coalesce during the steamy romantic wilds of a jungle-set jewel hunt.

When I was a kid, Romancing the Stone was one of my favourite films and I’m not lying! But now that I’m all grown up I know that such concepts of romance impress upon childhood in specific ways. Having no experience of romance, popular culture representations of romance ignite for children and teens the mystery of a romantic adulthood to be experienced one day in the not-so-distant future. Romance is pitched at kids because if you’ve had no experience of it, you have no frame of reference to judge false promises.

Romance may appeal to the liminal imaginations of childhood, but it’s no secret that the genre is for women, even when it’s written by men. Pedro Almodóvar’s The Flower of my Secret (1995) inverts the gendered significance of the romance novelist stereotype. The titular ‘secret’ is the true identity of romance novelist Amanda Gris, who is really just a pseudonym for male writer Leo Macias. Even the Australian film Paperback Hero (Antony J. Bowman, 1999) depicts the gendered significance of the romance writer. Hugh Jackman is the romance novelist this time and he’s the idealised macho vision of the Aussie male. That is, if you like the rugged outdoorsy truck driver type. The tagline for Paperback Hero sums up this type of Aussie bloke: “He’s hard, tough… and doesn’t give a XXXX for anything... except romantic novels.” If romance fiction relies on stock gender stereotypes, it certainly requires that the authors of such novels are the living embodiment of the stereotype. It’s a Jackie Collins kind of thing… or Barbara Cartland if you’re Blue Rinse.

That Hugh Jackman is a novelist hiding behind a female persona shows how romance fiction constructs the author as much as it constructs readers. The romance writer does not just write romance novels, she writes herself (or himself as her). Female consumers of romance fiction buy into the doubling of romance represented: the longings of the romance writer thinly disguised in formulaic plotlines that arouse precisely because of narrative blueprints predicated on repeated happily ever afters. In terms of how it functions through repetition and arousal, romance is a kind of pornography and the happily ever after is the ultimate ‘money shot.’

Romance, therefore, is narrative and like narrative, romance is incompatible with reality. Illusory and erroneous, romance as a representational system lacks a real-world referent. The structures of any narrative cinema, be it Hollywood or not, depends on the consummation of heterosexual imperatives in the quest for narrative closure. In his essay on My Own Private Idaho (Gus Van Sant, 1991) Thomas Waugh, writing in The Road Movie Book (Routledge, 1997) explains that narrative closure is impossible because the film is an unrequited queer romance. Waugh argues that narrative cinema is based on “the structures of sexual difference inherent in Western (hetero) patriarchal culture.” In Private Idaho, melancholy and longing cast a narcoleptic shadow on romance, the consummation of sexual attraction kept at bay. Unlike hetero romantic comedies, Private Idaho revels in imagination rather than reality, because the reality brings anguish and pain. The oneiric and intangible nature of romance reveals how narrative closure does not coincide with the money shot of sexual consummation as it does in hetero romantic-comedies. Rather, narrative closure is a myth and only exists in death. As gay-themed films of this period often bore the specter of the AIDS crisis – take Philadelphia (Jonathan Demme 1993) for instance – narrative closure indeed coincides with a nexus of sex/death.

When I think of romance in its ugliest manifestation, I think of Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. The pornography of romance is never more evident than it is in Nora Ephron’s rom-coms starring both Hanks and Ryan: Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and You’ve Got Mail (1998). A big year, 1993 saw Hanks sleepless in Seattle and dead in Philadelphia. Narrative closure for the conventional romantic comedy coincides with the ultimate coming together of the male and female protagonists. If death features at all, it’s la petit mort, which refers to the idea that a good orgasm is like ‘a little death.’ Unlike Meg Ryan’s simulated café orgasm in When Harry Met Sally (Rob Reiner, 1989) the money shot in Ephron’s films is only ever implied. Ephron’s films typify romance as false consciousness, perpetuating myths about how romance functions as life, when in fact, if these films were taken verbatim, romance ends the minute the end credits roll, which corresponds with the very moment the couple are united sexually – even if the PG rating paints the sex as implication over porn. Everything else is A Prelude to a… Fuck.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Bareback Hero, 2007

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Bareback Hero, 2007Polemical essay for the 'Romance' issue of Runway.

Published by Runway, issue 10 in 2008.