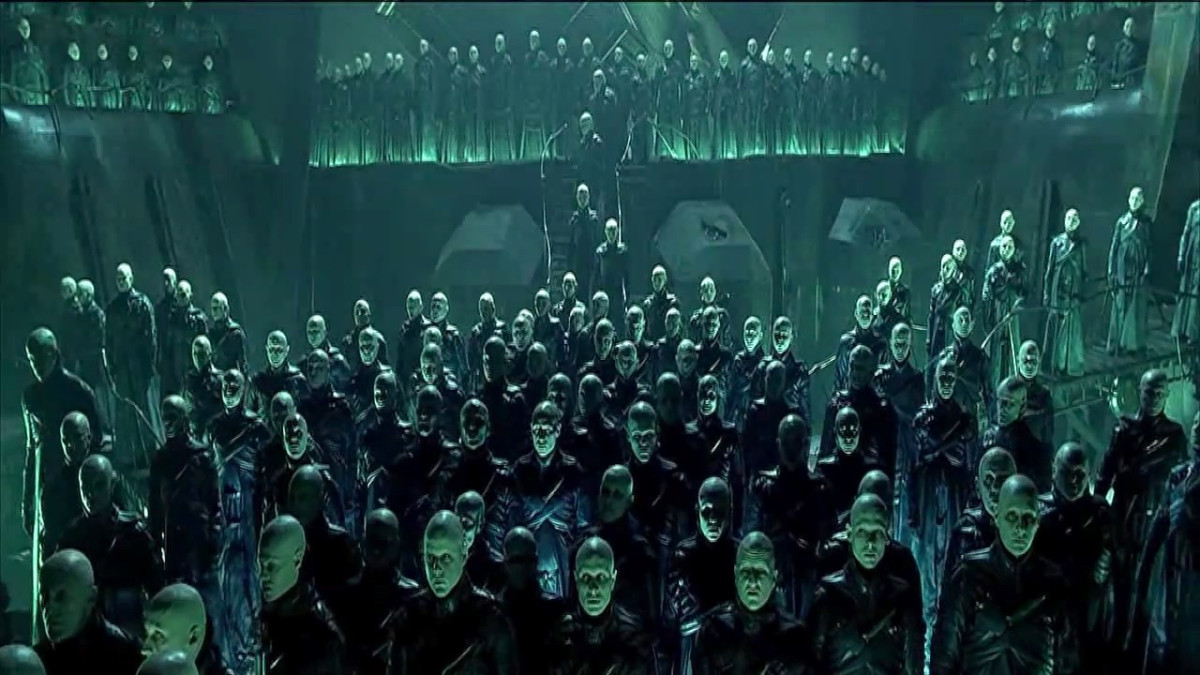

Alex Proyas, Dark City, 1997

Alex Proyas, Dark City, 1997I was a one-time film extra – playing an alien in Dark City (Alex Proyas, 1997). It involved having my head and eyebrows shaved and being doused with high density make-up and film lighting to imply lifelessness and death. Off set, I was perceived as such. Being white, skinny, and now hairless, friends said I looked like the ‘walking dead’ (one concerned colleague assumed I had HIV/AIDS).

I refer to this moment to make a point about how whiteness – pale skin in this instance – can signify death and decay, as much as it can represent virtue and morality. The use of lighting, or lack thereof in cinema often amplifies racialised – and racist – codes and connotations, implying that light and darkness are symbolic representations of good and evil.

Fellini once said, ‘films are light’. Light is the essential ingredient of celluloid. The way an actor is lit often influences the way we read their character. The technicalities of exposing, developing, and projecting film also depend on light. Film is a technological canvas that forms its images from light. Film theorist Richard Dyer argues that films are ‘centrepieces in a whole culture of light that is founded on... the effect not only of advantaging white people in representation and of discriminating between and within them, but also of suggesting a special affinity between them and light.’

In other words, the use of film lighting favours whiteness because white skin absorbs and reflects light in a more obvious way than it does for black skin. Even though cinema privileges whiteness, this is rarely acknowledged, probably because whiteness is the unmarked norm – as an aesthetic property it is invisible, empty, colourless. Dyer writes that whiteness ‘secures its dominance by seeming not to be anything in particular.’ The white face in cinema, however, is not such an empty signifier. Film lighting can be used to emphasise the innocence, purity and virtue of whiteness. Paradoxically, the same kind of lighting can emphasise cold, deadly and evil characteristics.

Garbo on the set of Queen Christina, 1933

Garbo on the set of Queen Christina, 1933In his famous essay The Face of Garbo, Roland Barthes describes Greta Garbo’s face in Queen Christina (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933) as a mask. Barthes argues that in the ‘clearest’ and most ‘heavenly’ light possible, the made-up face of Garbo is set with ‘the snowy thickness of a mask: it is not a painted face, but one set in plaster’. Barthes gives us the impression that Garbo’s beauty is all surface. It is the artifice of her whiteness and mask-like face that cements her beauty. It seems that the beauty of the white face is a mere surface hiding whatever lurks beneath. It is a beauty that is essentially sinister. Like a plaster mask, the surface of the white face may crack, revealing itself as masquerade.

Garbo’s face represents a specific kind of masked glamour. Cinematic archetypes like the virgin, mother and vampire represent the white face as either a mask of death, darkness, life or light. Elizabeth (Shekhar Kapur, 1998) also uses lighting techniques to suggest the mask-like aristocracy of the Virgin Queen’s face (Cate Blanchett). At the beginning of the film, Elizabeth’s virginal innocence is emphasised by natural daylight that crowns her hair like the supernatural shine of a halo. Her older stepsister Queen Mary Tudor (Kathy Burke) is suffering from cancer, and her face is streaked with darkness to signify disease, providing a stark contrast to Elizabeth’s translucent youth and beauty. The emphasis of light on Elizabeth’s face signals an idealism that strengthens in the face of Catholic repression. When Elizabeth first enters Mary’s chamber, her face illuminates the dark interior suggesting that Elizabeth’s idealism (or heresy) can be linked to light. Before Elizabeth is crowned queen, she steps outside, passing through an all-encompassing and transforming light.

Shekhar Kapur, Elizabeth, 1998

Shekhar Kapur, Elizabeth, 1998Though the lightness of Elizabeth’s face parallels her virginal idealism, it shifts subtly as her stoic character develops. Natural light is abandoned for studio lighting, which bleaches Elizabeth’s face, turning it into a ghostly countenance. Elizabeth’s face is often shot through veils, scrims, grates and windows signify its masklike character. After Elizabeth rids England of its enemies, she exclaims, ‘Must I be made of stone?’ She answers her own question by painting her face white, further emphasising her cold virtue.

The use of lighting emphasises whiteness, not to call attention to race, but to signify virtue and morality. The Western tradition of Judea-Christianity has held a long history of representing its icons as if they are lit from within and illuminate their impure (or non-white) surroundings.

Ang Lee, The Ice Storm, 1997

Ang Lee, The Ice Storm, 1997Joan Allen is another example of the white woman’s face as a ‘masked’ kind of beauty. Set in Connecticut, 1973, The Ice Storm (Ang Lee, 1997) features Allen as Eleana Hood, the long-suffering wife of a philandering Kevin Kline. Like Queen Elizabeth, Eleana’s whiteness is portrayed as a mask of firmly set respectability that can only crack through confrontation. In most scenes, Eleana appears in domestic interiors. The tungsten light does not illuminate her face any more than it does her family, but her domesticated presence is emphasised by her flawless complexion, dress sense and hair design. Eleana is rarely presented in close-up; instead she is depicted in relation to her family or peers, which serves to eliminate her autonomy as a wife and mother. By contrast, one scene represents Eleana alone, riding a bike on a steep incline. The natural daylight thaws out her white porcelain face, restoring life to what is otherwise a mask of domesticity.

The Ice Storm depicts the ambivalence of sexual liberation and family relations in the early seventies – a time when second-wave feminism was emerging and women were questioning and rejecting domesticity. The Ice Storm illustrates the way whiteness and masculinity often shape contemporary culture and representation through a process of exclusion.

Abel Ferrara, The Addiction, 1995

Abel Ferrara, The Addiction, 1995Shot totally in black and white, The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) stars Lili Taylor as Kathleen, a PhD student who, during her studies, reconciles the nature of addiction. Kathleen’s research is accelerated by the fact that she has been recently made a vampire by Casanova (Annabella Sciorra). Kathleen finds herself shunning light for darkness, preferring blood to burgers.

The Addiction uses vivid lighting to illuminate Kathleen’s face, emphasising her sexual, physical and spiritual decay. As Kathleen sustains her life by feeding off others, her face becomes sickly and anaemic. When Kathleen meets veteran vampire Peina (Christopher Walken), he declares: ‘You’re not a person. You’re nothing.’ The stark whiteness of Kathleen’s face is a kind of ‘nothingness’ used to signify death and decay. Even though vampires loathe light, Kathleen’s decaying whiteness is produced through strong studio lighting, forming the basic paradox of the film. The use of light is perfect for casting dark shadows which emphasise the moral contrasts of good and evil.

The virgin, mother and vampire suggest varied ways of giving (white) face in cinema. Film lighting is important for reinforcing the way moral codes are viewed and judged. If the white face is constructed according to moral standards, is it possible to undermine these representations and create new ways of thinking about whiteness and how it can be decentred? Light may illuminate the white face, but as a ‘mask’, the white face is constructed not only by what it suggests, but also by what it hides.

Originally published as 'Pale Face'

Re-edited, December 2021

Essay on whiteness in cinema for the 'Black and White' themed issue of IF Magazine - then known as Independent Filmmakers.

Published by IF Magazine, issue 16 in 1999.