Liam Benson, The Bowerbird Queen, 2012

Liam Benson, The Bowerbird Queen, 2012Courtesy of the artist and Artereal Gallery, Sydney

For the last two decades Liam Benson has worked across multiple forms of media. Through performance, photography, video, and, more recently, textiles and embroidery, Benson has critically harnessed the seductive codes of advertising, film, and media to decentre Australian attitudes to gender, sexuality, race, and cultural identity. Right from the start his bold and uncompromising body of work began with the body, his body. Adorning that body is a queer language of drag that is important for the statements it makes about the spectrum of gender, in binary and all its non-conforming terms. As much as Benson has been recognised for his use of drag, what is often misconstrued is that his work has predominantly engaged with what it means to be male in Australia when the dominant trope reverts to cis-gendered toxic masculinity. As such, Benson’s most powerful and complex photographic self-portraits see him inhabiting Captain Cook, Ned Kelly, and Jesus Christ: all familiar icons of colonial, criminal or religious inference.

Benson’s affiliation for life beyond the centre was embedded from childhood. Born in Westmead in 1980, he grew up in Glenorie in the rural northwest region of New South Wales. His emergence on the Sydney art scene occurred almost immediately after graduating from the now-defunct art school at Western Sydney University (then UWS Nepean) in 2002. The influence of Western Sydney was strong in his work and has remained so. From its inception, Benson’s aesthetic was crafted from the socio-political complexities of suburban life as he experienced it through the lens of his own queer, working-class whiteness. “Initially my work was informed by existing in suburban Western Sydney, and the consumption of pop culture and media – these sources are still relevant, although now it’s social media instead of the newspaper, and podcasts instead of magazines.” This awareness of the mutability of culture and a responsiveness to that change animates his evolution as an artist. “The conversation within my work has grown from a solitary reflection on our contemporary world, to a tapestry of connections, conversations, and relationships.”

This “tapestry” manifested through a textile and embroidery practice that commenced in 2013, with works often made through participatory community collaborations and workshops. By involving others in the creation of these works, his earlier focus on self-portraiture has expanded to include the hand of the collective with an emphasis on joint authorship. “I wanted to go from a solitary, introspective way of making work, to a connected, collaborative practice where I could directly talk to people through art,” says Benson. Trading his earlier use of performance for participation, Benson’s work today aims to share space and perspectives directly with the community and especially people outside his everyday life. Using beads, sequins, and thread, Benson and his collaborators create works that portray text fragments, Australian maps, and abstracted depictions of the landscape and body to reflect self and other through socially engaged practice and community building.

Making with materials is like muscle memory for Benson. He grew up creating with his mother and grandmother, both skilled makers whose legacy lives on through their progeny. Later in life Benson had a drag mother who imparted technical skills and cultural knowledge of the queer community. Each of these maternal figures taught him how to tap into an instinctive response to materials as much as they instilled a respect for tradition and storytelling. Though his work interrogated masculinity initially, it now primarily unpicks concepts of queer and gendered labour in the context of craft practices once inherently matriarchal and traditionally classified as women’s work.

Liam Benson, The Opal Queen, 2012

Liam Benson, The Opal Queen, 2012Courtesy of the artist and Artereal Gallery, Sydney

Though he came to prominence with photographic self-portraits drawing on personal experience through politics, pageantry, and pop culture, he has always wanted to connect the stories and challenges of our times with how they manifest, and in whatever form. The matriarchal facets of his work have been most strongly expressed in a series called Motherland, 2012, created as a tribute to his mother soon after she died. In one image Benson references the monarchy by channelling the spirit of his mother through Queen Elizabeth II. In queering personal family experience alongside colonial systems of political governance in Australia – and by extension the supposed “motherland” of Great Britain – Benson conveys robust political critique through welcoming and inclusive conversation. “Making work about the systems of power like the British monarchy, and our fraught relationship with our colonial past, has removed the anxiety around our cultural progression,” says Benson. Reflecting on the Queen’s recent death, the artist believes there is a growing sense that we are listening to each other and empathising with each other in unprecedented ways. “I know we will participate in a major cultural change and I’m confident we will do this through knowledge, not anxiety,” he offers.

Benson’s latest offering is a survey reflecting on the last twenty years of practice, and indisputably his most important exhibition to date. Its title, Virtue Without Stain, is a nod to his Scottish matrilineal ancestry and their Clan Russell motto dating back several centuries. Kicking off at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery (BRAG) with a regional tour to follow, the exhibition is curated by Richard Perram, who previously included Benson as one of sixty-two Australian and international artists assembled for the major exhibition The Unflinching Gaze: photo media & the male figure at BRAG in 2017. What Virtue Without Stain demonstrates, whether by turning the camera back on himself or sharing sequins and beads with others, is how the politics of identity and community have never been more complicated. The burdens of our colonial past continue in the present as the necessary implications of truth-telling come to pass. Benson’s body of work has consistently been a crucible to examine these ideas, their necessity, and their volatility.

On what it means to reflect on his own past as an artist, he says: “It’s both revealing and at times unnerving to revisit it in one exhibition. I feel my work reflects on how we have advanced in our awareness, and yet the space this creates for further growth is sobering.” On what the next twenty years might look like, he adds: “My work will continue to be a space for people to come together and share interests and passion, where we can celebrate what we have in common.”

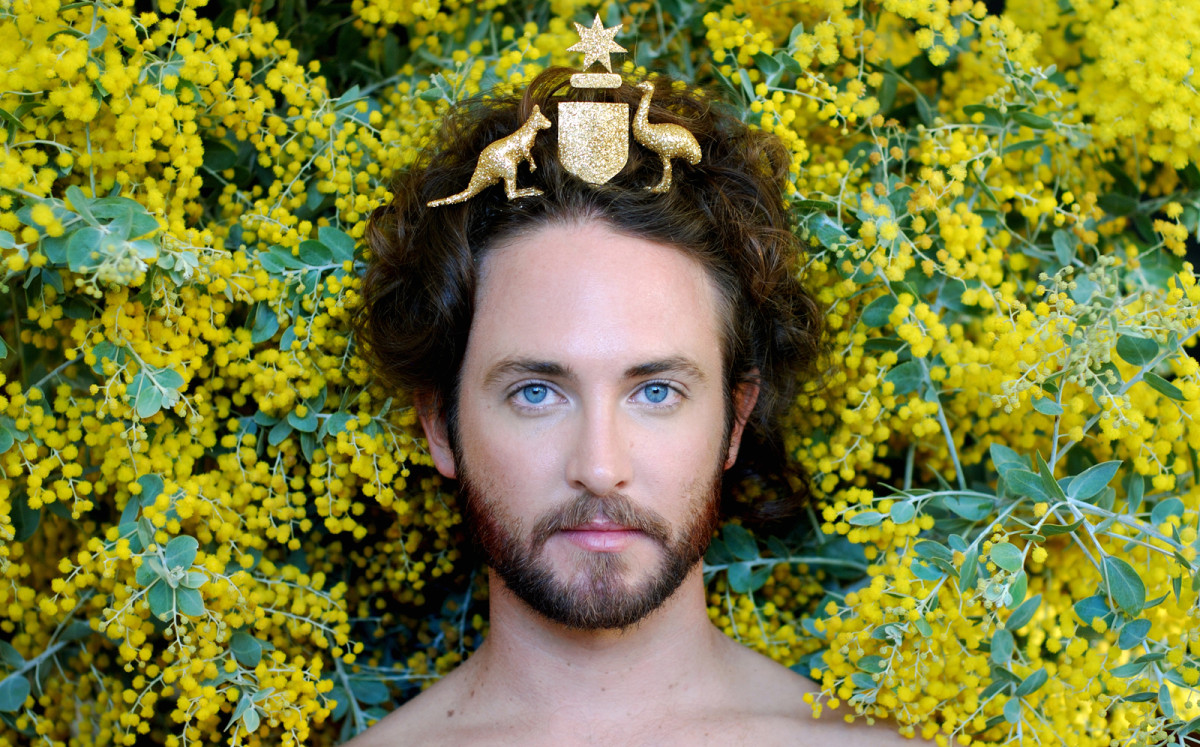

Liam Benson, Coat of Arms, 2009

Liam Benson, Coat of Arms, 2009Courtesy of the artist and Artereal Gallery, Sydney

Essay for Artist Profile

Published by Artist Profile, issue 61 in 2022.