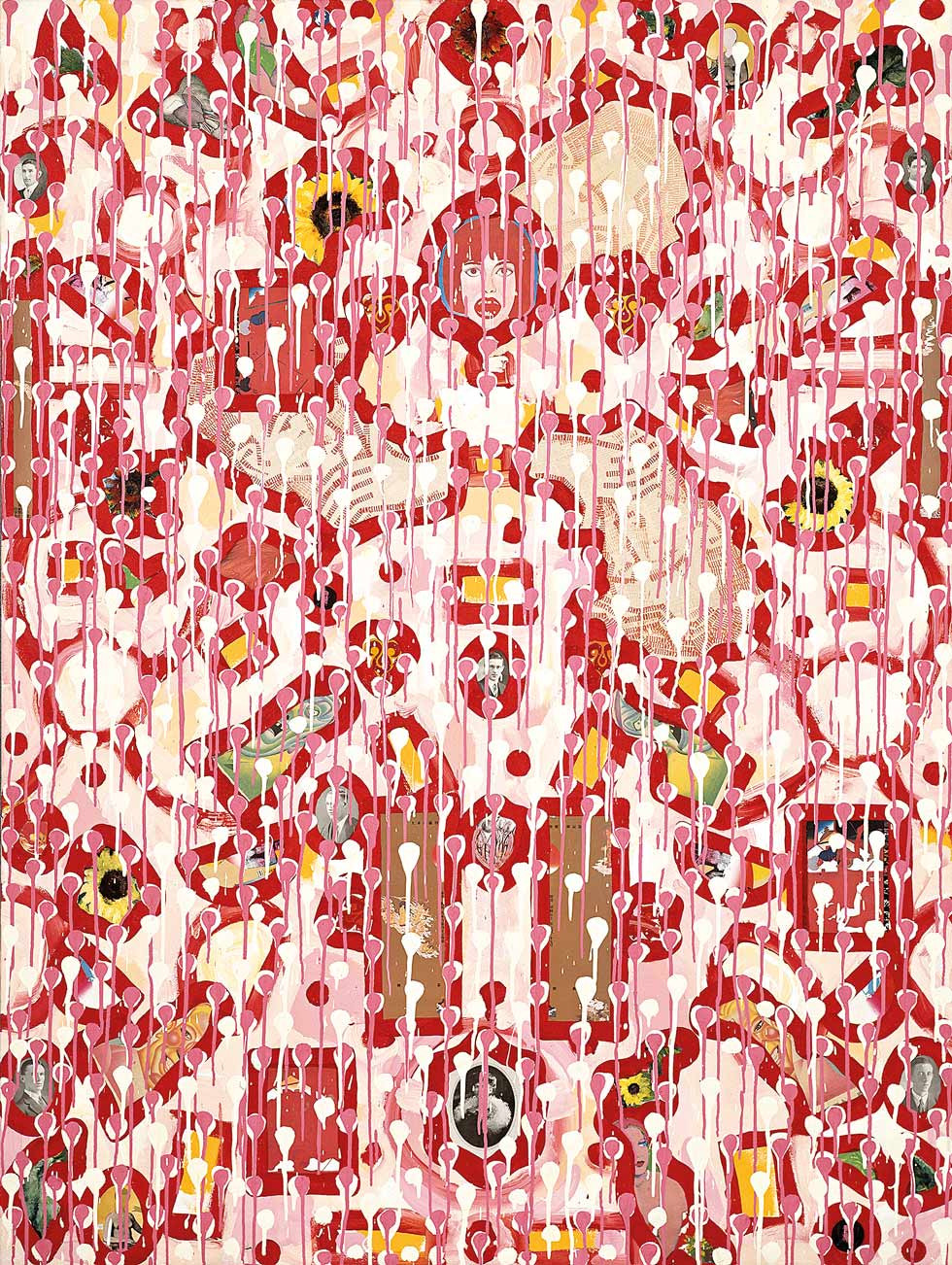

Arthur McIntyre, East Meets West, 1988

Arthur McIntyre, East Meets West, 1988Collection: National Gallery of Victoria

My art wears many skins and is as intimate as fucking.

— Arthur McIntyre

James Mollison’s last professional speaking engagement before his retirement as director of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) was delivering the opening address at Arthur McIntyre’s solo exhibition, Life, Sex, Death, Décor, at Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney in 1995. Mollison had been a longstanding champion of McIntyre and purchased several of his works for the NGV and National Gallery of Australia when he was director there. After a visit to McIntyre’s studio in February 1991, Mollison proposed a mid-career survey of McIntyre’s work for the NGV. One of McIntyre’s last solo exhibitions, Life, Sex, Death, Décor should have been the precursor to much greater recognition and the consolidation of some 25 years of practice as an artist of unruly discipline, erudition and flair. Nothing could be further from the truth: the corporate sponsor for McIntyre’s NGV show, Ericsson, withdrew their support in favour of a sports event, bringing a permanent halt to its realisation.

Arthur McIntyre (1945-2003) came to my attention while I was undertaking research for Bent Western, an exhibition I curated for Blacktown Arts Centre. Surveying work by sixteen queer artists with connections to Western Sydney, Bent Western charted three decades of work, in keeping with its placement in the 30th anniversary of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras cultural festival. To an extent, Bent Western reflected my own experience of living and working in Western Sydney since 1993 and being part of a community of lively queer artists, most of whom I have known for some time. While most of its content was drawn from the late 1980s until the present, the inclusion of McIntyre, who was born and raised in Katoomba, grounded the show in a broader Australian art history than I had anticipated.

McIntyre was a figure who very much stood at the divide between late modernism and postmodernism. Bred on an appetite for cinematic montage meshed with an obsessive regard for figurative abstraction, McIntyre made work that consistently embraced the body and sexuality in cut-and-paste arrangements that curiously sidestepped the emerging high theory affectations of 1980s postmodernism. A widely respected art critic and teacher, McIntyre brought to his practice a broad-ranging knowledge of other people’s art; his aptitude for lucid and unpretentious art criticism was firmed by the books he published and the comprehensive drawing and collage survey shows he curated.

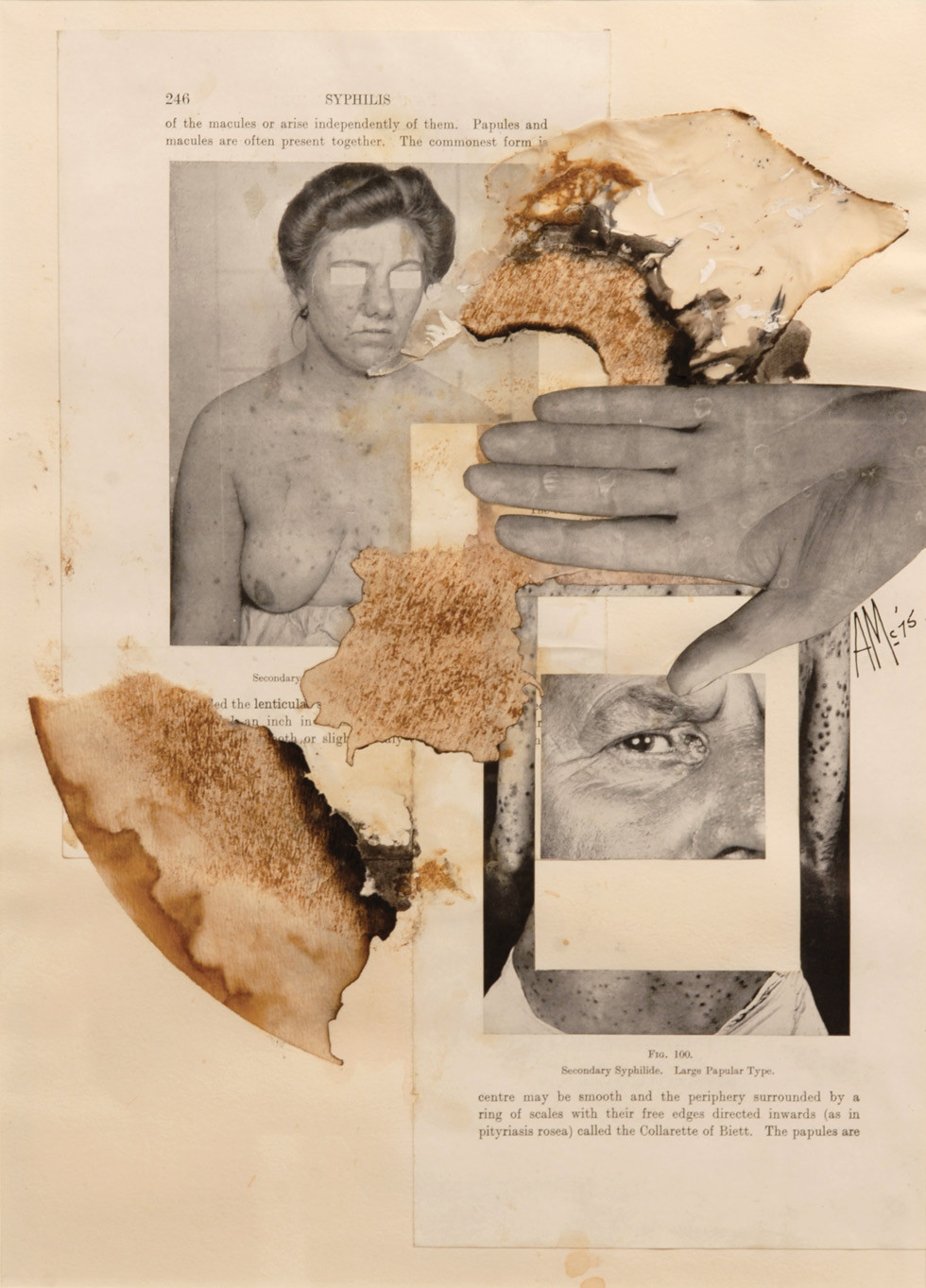

A scholarship-winning graduate of the National Art School, McIntyre’s early influences were teachers John Coburn and David Strachan. As a child, McIntyre was mentored by Jeffrey Smart who during the 1950s, under the pseudonym Pheidias, hosted the children’s art program for ABC Radio called Argonauts Club. McIntyre sent drawings to the program on a weekly basis and Smart regularly broadcast commentary on McIntyre’s precocious talent. Though McIntyre began presenting solo exhibitions as a professional artist in 1969, it was not until Survival Series (1975-78) and Survival and Decay Series (1976-79) that he came to public prominence. Consisting of mixed media collages that juxtapose erotic imagery with medical textbook documentation of venereal diseases, and arranged in a way to emphasise their decaying and waste-like materiality, these images shocked audiences and appealed to critics of the day. Nancy Borlase proclaimed McIntyre a major talent whose work ‘comes close to the fantasy and protest themes of the German Dadaists, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann. His formally cohesive, bitter images of erotic hedonism, with their dislocated time/space relationships, convey a similar sense of moral indignation.’

The Survival Series works are still important today because by juxtaposing sex and disease, they pre-empt an AIDS crisis that was just about to erupt globally. Reflecting on these works in his own book about Australian collage, McIntyre writes: ‘In retrospect, my series on sexually transmitted diseases was hideously prophetic in our age of AIDS. My intention was never to preach, nor moralise … I was simply intrigued that so much suffering can result from acts of love – and by notions related to pleasure, pain and death.’

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Syphilis, 1975

Arthur McIntyre, Survival and Decay Series: Syphilis, 1975Collection: Daniel Mudie Cunningham

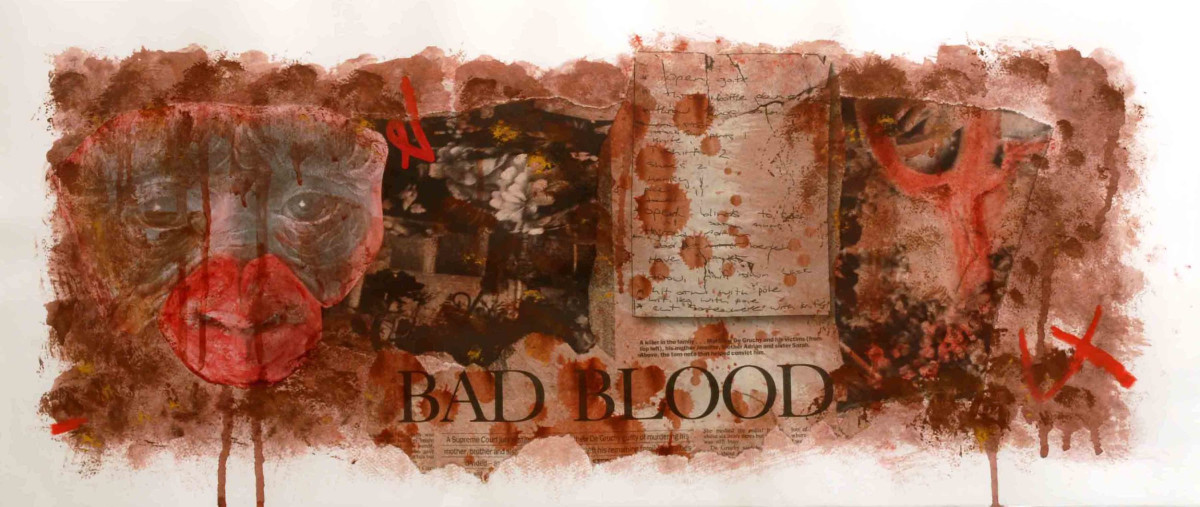

The process of curating a survey exhibition about ‘regional’ gay and lesbian art spanning the last three decades, inevitably prescribes a social context defined by ‘queer’ subcultural textures, smoothed over by a gradual absorption into the cultural mainstream. The most vivid queer cultural expressions of the period have been about the AIDS crisis, evidenced by US activist art groups like ACT-UP and Gran Fury. Indeed, the last 30 years of queer culture is one marked by the horror of the AIDS crisis, and while Bent Western was not overtly about AIDS per se, it certainly acted as an important trigger for some of the darker depictions of violence and trauma depicted therein. As McIntyre’s work tapped into these themes, but was rarely contextualised within queer art circles, the process of ‘unearthing’ his work became one of the most compelling facets of curating the show. Three images from the Survival Series were included in Bent Western alongside two works from the series Birth Pains (1975); Art and Man (1986) – a large work loaned from Macquarie University Art Collection; and finally, three related works from late in his career: Bad Blood, Investigation and Excavation (all 1999). The latter works were evocatively titled because researching McIntyre could be likened to a process of ‘investigating’ and ‘excavating’ the work of a dead artist with a longstanding passion for ‘bad blood’. Overall McIntyre’s contribution to Bent Western became its curatorial anchor and resonated alongside the work of other artists like Michael Butler and Kurt Schranzer who also use collage and drawing in semi-modernist and sexually charged ways.

Unsurprisingly, the last significant group exhibition McIntyre was included in during his life was about AIDS. Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS at the National Gallery of Australia (1994-95) saw McIntyre’s work contextualised alongside that of Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Derek Jarman and Australian artists including Juan Davila, David McDiarmid and William Yang. In a letter to McIntyre, curator Ted Gott described his contribution, Monument to Intimacy – The Last Embrace (1994), as ‘the most impactful’, while Sasha Grishin commended it as ‘one of the most powerful exhibits’ on show.

As I delved deeper into researching McIntyre, it became obvious that ‘survival’ and ‘decay’ are themes that shaped his life as much as his work. Despite praise from Mollison and curators that included Ted Gott and Andrew Sayers, McIntyre felt alienated by the art world throughout his life, making him more determined for survival and recognition as an artist. While poring over the vast archive of letters, writings and neglected art works held to this day in two dusty Sydney storage containers, I could not help but feel that decay had well and truly set in: ‘When I am dying I want to be able to look around at mountains of work’, writes McIntyre. ‘It does not bother me that much of it will be rotting and providing fodder for insects.’

An obituary for McIntyre by lifelong friend Peter Phillips claims that McIntyre felt ‘blacklisted’ by the Sydney art establishment for being embroiled in a couple of highprofile art scandals.

After the cancellation of the NGV mid-career survey, McIntyre’s enormous output as an artist continued, though he exhibited rarely and public interest in his work waned. Peter Phillips explained to me how those closest to McIntyre believe the NGV setback accelerated his deteriorating mental health, brought about by a lifelong battle with inherited bipolar condition and clinical depression. When he died from heart failure in 2003, his mental and physical health was at fever pitch. The last exhibition listed on his curriculum vitae is Vicissitudes, held at the now defunct gallery DQ on Oxford in 1997. Billed as a retrospective, Vicissitudes comprised unsold works from his studio, spanning a career and dating as far back as the watershed years of the mid-1970s. It may not have been the auspicious institutional mid-career survey he deserved, but McIntyre was not about to lose his sense of the absurd, referring to Vicissitudes on the invitation as ‘a low budget off-Broadway production’. Better yet, the opening promised the attendance of two nude waiters.

Bruce James wrote of Vicissitudes: ‘For stamina alone, McIntyre is surely a legend of Australian art. There can be few of his peers who have adhered to such consistency of purpose to a single vision.’

Arthur McIntyre, Bad Blood, 1999

Arthur McIntyre, Bad Blood, 1999Collection: Wollongong Art Gallery

- Arthur McIntyre, artist statement for Life, Sex, Death, Décor, Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney, 1995.

- Arthur McIntyre published two books: Resurgence and Redefinition: Australian Contemporary Drawing (Boolarong Publications, Brisbane, 1988) and Contemporary Australian Collage and its Origins (Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990). His curated exhibitions include Oz Drawing Now (Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney, 1986), The Age of Collage (Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney, 1987), Intimate Drawing (Coventry Gallery, Sydney, 1989), Mass Media – Mixed Media (Painters Gallery, Sydney, 1990) and Sydney – From the City to the Fringes (Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney, 1991).

- James Mollison, cited in Bronwyn Watson, ‘Arthur McIntyre’, Oz Arts Magazine, issue 1, Spring, 1991, p. 17.

- Nancy Borlase, ‘McIntyre’s new breadth of vision’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March, 1977, p. 7.

- Arthur McIntyre, Contemporary Australian Collage and its Origins, Sydney, Craftsman House, 1990, p. 130.

- Sasha Grishin, ‘Restraint replaces horror’, Canberra Times, 6 December, 1994, p. 18.

- Arthur McIntyre, artist statement for Life, Sex, Death, Décor, Holdsworth Galleries, Sydney, 1995.

- Peter Phillips, ‘Challenge to art world a cry in the dark’ [obituary for Arthur McIntyre], Sydney Morning Herald, 5 December, 2003, p. 30.

- ‘Pollocks fake, says art expert’, The Australian, 4 May, 1978, front page. Though credited to Sandra McGrath and Andrew Fowler, it is widely documented that McIntyre co-authored this article with Fowler. McIntyre kept a copy of the invoice for his contributor payment of $50, and his full story on the incident appeared in Art Monthly [UK], June/July issue, 1978.

- Bruce James, ‘Galleries: Limbs like Leonardo’, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 August, 1997, p. 14.

Essay for Art Monthly Australia.

Published by Art Monthly Australia, issue 211 in 2008.