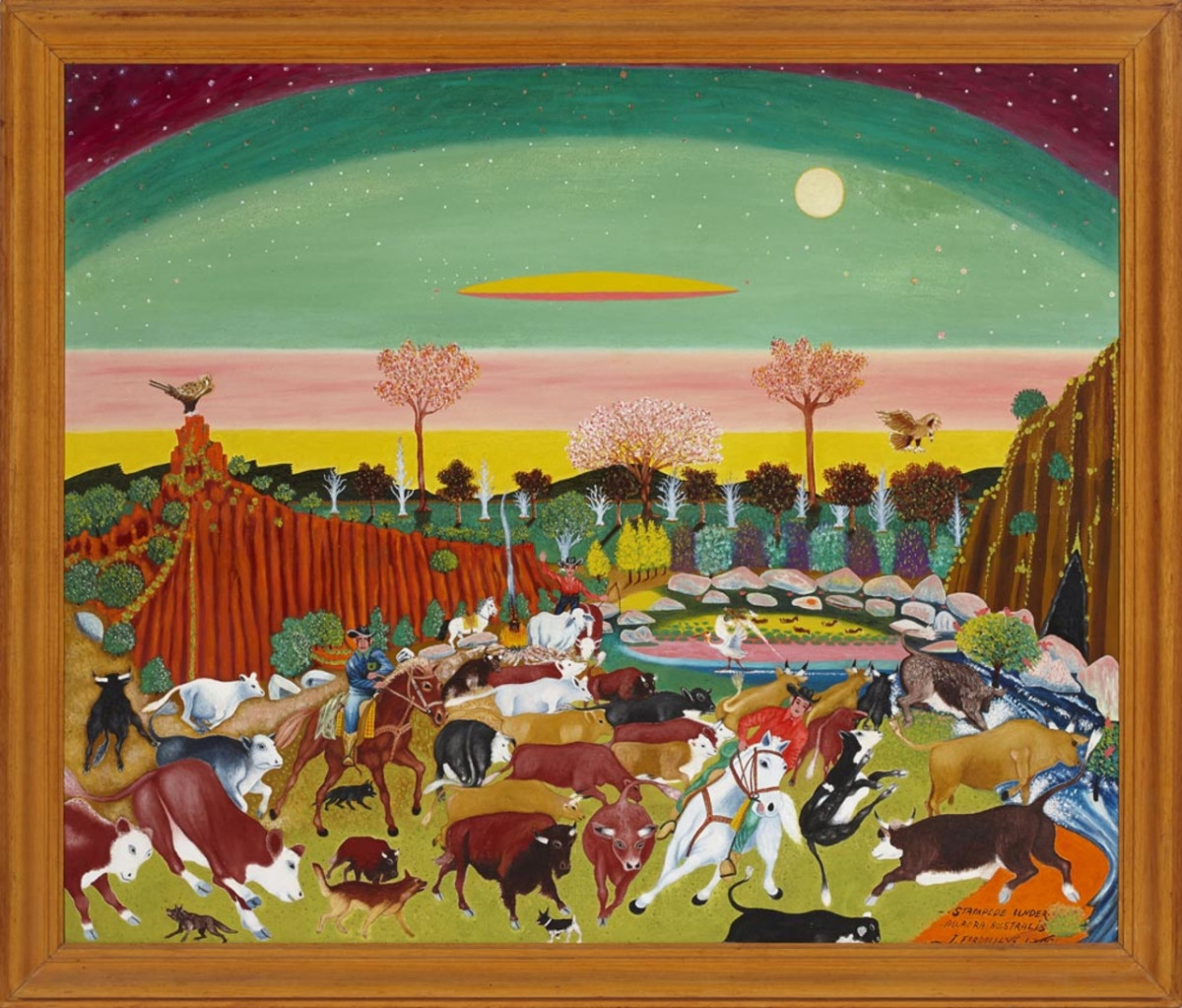

James Fardoulys, Stampede Under Aurora Australis, 1971

James Fardoulys, Stampede Under Aurora Australis, 1971Collection: Artbank

A lurid shock of candy-coated colour assaulted my retina the day I unexpectedly encountered Stampede under Aurora Australis (1971) by James Fardoulys. Located deep within the recesses of Artbank’s collection store I was on a quest for another work — one I now don’t recall. A temporary amnesia brought on no doubt by the visceral stage-dive that occurred when this action-packed painting greeted my imagination.

Truth be told, it wasn’t the hectic rural stampede fairytail scene — complete with ‘flying saucer sky’ — that initially drew me in. Rudely, the picture had its back to me as I rifled through a group of similar sized paintings from the collection. And yet, the gorgeous cluster of inscriptions and labels denoting its rich provenance piqued my curiosity. The elegant typefaces of the past, the quaint markings of the artist’s hand, the journey from one art prize to another spelt out by various registration markings formed a preconception in my mind.

I was expecting a quaint still life or genre scene to unfurl as I turned it around. Instead I was confronted with a dazzling picture defying all expectations — one that literally made me laugh out loud — LOL, as it were — when surveying the tiny naïve masterpiece squatting benignly in a parking spot I’m sure it had inhabited, unmoved for years.

It was an encounter I can only describe as being introduced to a future ex-boyfriend. I played it cool knowing what was revealed at face value shrouded a delicious mystery that made me want to get on Google and stalk his Facebook page. Recto: he had all the trashy glamor of a Saturday night on the town. Verso: he was a potential puzzle begging to be solved. All of a sudden, it was a he.

Using my best curatorial stalking skills, I set to work on decoding this mystery. For starters, stuck verso was a label from the Art Gallery of New South Wales that said: “With the Compliments of the Director.” I chuckled imagining past AGNSW gallery directors deaccessing works by mailing them as ‘with compliments’ slips to acquaintances and friends.

Imagined follies aside, the label aroused questions of its history. Initially I wondered if it had come compliments of the AGNSW! Of course it hadn’t — Stampede under Aurora Australis had been a finalist in the Wynne Prize in 1971, but shown off-site at what was then Farmers Blaxland Gallery and what is now Myer (this was the last Wynne exhibition to be staged elsewhere as AGNSW was under construction).

Other verso tertiary inscriptions reveal the work had also been entered into the HC Richards Memorial Prize at the Queensland Art Gallery and the Royal National Agricultural & Industrial Association of Queensland. Not evident among these inscriptions was another prize entry — it had also been a finalist in Brisbane’s ‘Warana-Caltex Oil, Watercolour, Sculpture and Pottery Contest’. Fardoulys was a regular entrant after being awarded joint first prize (with Roy Churcher) in 1964. So frequent was Fardoulys an art prize entrant that he once remarked, with a flair for self-aggrandisement: “The only time I have had an open exhibition with open honest judges — I got first prize. Therefore I have been robbed seventeen times by corrupt administrators.”

I know the feeling.

Enriched with the knowledge of its exhibition and prize history, three pressing questions still hammered away in my busy brain. How did Artbank come to own this work? Who the hell is James Fardoulys? And why has this whole encounter cast this spell?

In 2010, the Queensland Art Gallery mounted ‘James Fardoulys: A Queensland Naïve Artist’, the only retrospective of the artist’s work to date. Curated by Glenn R Cooke, the show included forty nine works spanning a period of 1961 to 1973. Seems like a short period of time for a major survey of an artist’s work. It is. The reason being James Fardoulys took up painting late in life after retiring from driving cabs around Brisbane for almost three decades. Self-taught aside from compulsory lessons in school, he dabbled in painting prior to retirement from his day job when he decided to — as quoted in a 1968 Australian Women’s Weekly article — “give the art a go”. During his lifetime Fardoulys achieved a modicum of recognition, as either a ‘primitive’ or ‘naïve’ artist depending on the sophistication of the art writing. Certainly the eccentric approach to perspective, the unmixed colour and the fusion of historic and imagined scenes in his paintings are all the hallmarks of a naïve artist. Artist Roy Churcher was a fan who articulated the style of Fardoulys’s work: “The naïve painter is uninterested in painting, his interest is in pictures, and he uses his paintings solely as a vehicle to carry his memory visions. One never feels the style in which they are painted is consciously arrived at, but instead is again the result of conscious visual impregnation… What a marvelous cultural cross fertilization to see brumby, windmill and parrot take the old Greek gaze.”

Reading up on Fardoulys I was presented with a man whose life was just as colourful as the palette he presented to the world. Born in 1900 in Patamos, a village on the island of Kythera in the Aegean, Fardoulys migrated to Australia 1914 and worked in cafes in various locations in New South Wales and Queensland before marrying a ventriloquist and joining her travelling troupe. Fardoulys eventually settled in Brisbane, raised a family and took to driving cabs. Like any reputable cabbie he became a local identity known to brag of famous fares like Prime Minister Robert Menzies. He was often photographed in a white singlet, cigarette in mouth. Women’s Weekly described him best: “Jim Fardoulys is a medium-sized nuggety man with dark hair and very bright dark brown eyes. He believes in comfort and doesn’t like shoes.”

In 1966 he staged his first one-man show, Paintings and Drawings by James Fardoulys at Johnstone Gallery in Bowen Hills — an almost sell-out show. From then till the end of his life, Fardoulys received some success: he was collected by the National Gallery of Australia; had a small steady following with private collectors in Brisbane which extended to London when ex-pat Barry Humphries chanced upon his work and commissioned a portrait that was reproduced on Humphries’s 1968 book of Australian verse and which was hung in his London home. A painting even made its way to Oklahoma in the USA, returned only recently to the Fardoulys family via eBay.

A year after his death, Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art honoured Fardoulys by showing a selection of works alongside the work of Charles Callins with the tagline: “a tribute to two distinguished naïve painters”. Stampede under Aurora Australis was not included in this exhibition because it had already been acquired for what was then referred to as the National Lending Collection, which formed the basis of Artbank when it was established in 1980. When Stampede under Aurora Australis was transferred to Artbank in 1982 it had been displayed at the Australian embassy in Paris and in the offices of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Canberra. That Fardoulys’s unique fantasia of Australiana was hung in an official post abroad amuses me no end. Surely imagery of stockmen herding cattle is a visual staple in our national art history. However, it rarely conveyed the camp rodeo spectacle suggested by the numerous cowboys, animals and birds competing with a dramatically gradated skyline bejeweled with rhinestone stars and spaceship sun. All that’s missing is Doula, the artist’s beloved cat and muse who appeared in many other similar fantasy landscapes. Surely if Doula-as-meme was alive today she would be kicking around as an internet sensation with a flying saucer of milk. And Fardoulys would be the one making the GIFs.

- Jean Bruce, “Giving the Art a Go”. Australian Women’s Weekly. 10 April 1968: 8-9.

- Roy Churcher, A Tribute to Two Distinguished Naïve Painters: Charles Callins, James Fardoulys. Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 1976.

- Glenn R. Cooke, James Fardoulys: A Queensland Naïve Artist. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 2010.

Essay for Sturgeon.

Published by Sturgeon, issue 1 in 2013.