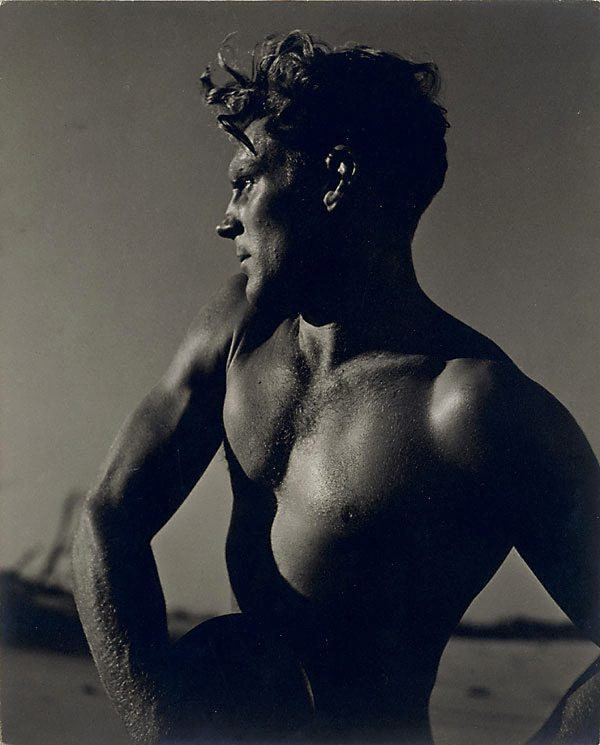

Laurence Le Guay, The Discus Thrower, 1947

Laurence Le Guay, The Discus Thrower, 1947Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

The culture’s privileging of masculinity means that the hegemonic bodily imago of masculinity conforms with his status as sovereign ego, the destroyer... The male body is understood as phallic and impenetrable, as a war-body simultaneously armed and armoured, equipped for victory.

— Catherine Waldby

The paradigmatic ‘straight’ ‘image of man’ is that of a hard body. ‘He’ is active, muscle-bound, well-hung and sexy. The popular representation of the gay male is often a feminising one. ‘He’ is usually represented as ‘passive’, ‘dandy’, ‘poofy’, camp and odd (when sexy ‘queers’ like Rock Hudson came out, Doris Day was not the only woman to be shocked).

Between the 1920 and 1950s—long before the ‘queer’ magazine Blue hit the news stands—where could the average gay male (if there could be such a creature) find some visual pleasure? The only magazines that were designed for men in this period were tabloids like MAN, which had very fixed ideas about what a ‘man’ was. ‘He’ was straight, white and male—this formula was made apparent by the contents of this magazine. MAN regularly featured caricatures of women sporting the latest in beach wear: visually, MAN was all about woman. MAN was also racist and valorised a white colonial perspective about Australian national identity—terms ‘Abos’ and ‘Japs’ were two frequently quoted examples.

The tension here is that Dupain and Burke were 'straight' artists whose predominant concerns with the male body were paradoxically both heterosexual and asexual. It was heterosexual in the sense that they were representing 'straight' male sexuality, and it was asexual in the sense that these photographers maintained a critical and artistic distance between themselves and their (sexual) subjects. This distance was maintained so that the images remained within the fixed realm of (an assumed) heterosexual representation and their sexuality was not called into question. But how 'queer' it all seems to us now in our body-obsessed 1990s, where the 'image of man' has as many gay associations as it does 'straight'. In reverse, if we are to use two popular Australian magazines, Blue and Australian Women’s Forum as examples, the 'queer' focus of Blue can be a site of visual pleasure for 'straight' women who are looking at the objectified gay male body, or 'straight' men curiously investigating lesbian bodies. The 'straight' focus of Forum, on the other hand, can be a masturbatory revelation for the gay voyeur. The representation of the male body has become so blurred that it can have as much fascination for men as it can for women. The reason for this blurring of sexual representations is the invention of the 'queer'.

Keast Burke, Husbandry 1, c. 1940

Keast Burke, Husbandry 1, c. 1940Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

According to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick 'queer' is a movement, not only in the sense that it is a community or a collective, but because it moves in the literal sense: "The word 'queer' itself means across ... The immemorial current that queer represents is antiseparatist as it is antiassimilationist. Keenly, it is relational, and strange."

To be 'queer' is to be in flux, to be passing and moving across sexualities, genders, desires and practices. The benefit of 'queerness' is that it does not allude to the specificity of sex and gender, as 'gay' and 'lesbian' categories do. 'Queer' refers to both the subject (whether individual or collective) and subjectivity (the practices or performances that may be 'queer'). The work of 'straight' photographers, like Max Dupain or Keast Burke, has the tendency to move across sexual contexts, both gay and 'straight', making these images paradigmatically 'queer' and, as Sedgwick observes, 'strange'.

What makes these images even stranger is the fact that there is little evidence as to why photographers like Burke and Dupain were obsessed with the male body. When he was editor for The Australasian Photo-Review (AP-R), Burke regularly published portfolios of his own photographs but he rarely cites any conceptual processes behind the work. Instead, Burke explicitly states his preoccupation with photographic technique and skill. Long before he was editor for AP-R, Burke wrote an article in 1912, with the title 'Two Boys and a Brownie'. In this article, Burke explains his interest in photography as: a recreational past-time, a steadfast obsession with different cameras and a preoccupation with photographic techniques:

I am an enthusiastic walker, and like nothing better during my school holidays than to select some spot of interest, and with a boy friend go on a walking tour, which will include the selected district... I have lately taken an interest in stereoscopic work, owing to the realistic way in which you can almost live your trips over again by means of stereoscopic prints in the stereoscope.

Keast Burke, Ride Pagliacci, 1936-37

Keast Burke, Ride Pagliacci, 1936-37Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

Burke's writing for AP-R was always anecdotal and punctuated with the technical "do's and don'ts" of taking good photos. However, Burke never gives any insight into why he endlessly photographed men. Burke's men were always workers—they had hard bodies, they wielded spears. Burke's images of men were not always virile. One image in particular, Ride Pagliacci (1936-37) depicts a laughing clown, donned in garb and theatrical make-up. Ride Pagliacci could be considered a feminising image insofar as it conforms to the representational stereotypes of the 'passive' gay male mentioned above. The clown provides a stark contrast to Burke's more virile images of the hard male body that contemporary 'queer' culture lusts over.

While Burke concentrated on male workers, Max Dupain’s images of men were quite ambiguous in sexual meaning. Dupain’s timeless image, The Sunbaker 1937, has become a symbolic representation of the bronzed Aussie body. If the Baywatch boys and babes are exemplary of what American ‘beached’ bodies should look like, then Dupain’s image is a more resonant and timeless Australian equivalent. Most of the writing devoted to Dupain, and The Sunbaker, concentrates more on the national iconography of his images, or what David Moore refers to as Dupain’s “rigorous discipline of selection [which] honed the statements to a precise edge.”

George Platt Lynes, Tex Smutney and Buddy Stanley (standing), c. 1941

George Platt Lynes, Tex Smutney and Buddy Stanley (standing), c. 1941Collection: National Gallery of Australia

The work of American photographer George Platt Lynes, was in direct contrast to the Australian photographic practices of Burke and Dupain. Lynes was an ‘out’ homosexual who worked prolifically as a photographer from the 1930s until his death in 1955. Not unlike Burke, Lynes also edited a magazine for most his working career. However, while Burke was content working as an advocate for the Kodak vehicle, AP-R, Lynes was a dedicated fashion and portrait photographer who worked as an editor for Vogue from 1945 onwards, while also regularly contributing to Town and Country and Harper’s Bazaar. The work of Lynes was obsessed with the ‘queer’ male body and celebrity portraiture. You could say that Lynes was the Robert Mapplethorpe of the 1930s and 1940s, except he did not have to deal with the interrogations of right-wing politicians.

The work showcased in The Image of Man primarily concentrates, with some exceptions, on the hard male body. Though the photographers in this exhibition were mostly a collective of ‘straight’ male photographers, their work can easily be read as ‘queer’. I doubt that any critical thought would have been granted to the homoerotics of this work between the period of 1920 to 1950. However, late in the 20th century, the work presented in The Image of Man moves across sexual contexts, both gay and ‘straight’, providing visual pleasure for men and women alike—making the work both quintessentially ‘queer’ and ‘strange’.

Furthermore, we are left to question why so many ‘straight’ photographers of this period were obsessed with the male body. I am not suggesting that photographers like Burke and Dupain were ‘queer’ men, but it is ironic that their work provides a timeless example of what constitutes sophisticated ‘queer’ photography.

Keast Burke, Untitled (Man in Surf), late 1930s

Keast Burke, Untitled (Man in Surf), late 1930sCollection: Art Gallery of NSW

- Catherine Waldby, ‘Destruction: Boundary Erotics and Refigurations of the Heterosexual Male Body, Sexy Bodies: The Strange Carnalities of Feminism, Routledge, London & New York, 1995 p.268

- For an excellent discussion on the queer refiguration of Rock Hudson’s ‘starbody’ see Richard Meyer, ‘Rock Hudson’s Body’, in Diana Fuss ed. Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, Routledge, London & New York, 1991 pp.259-288

- See H. D. A. Joske, ‘Abos as I Found Them’, MAN, Sydney, January 1939, pp. 64-65

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies, Duke University Press, North Carolina 1994 p.xii

- E. Keast Burke, ‘Two Boys and a Brownie’, The Australasian Photo-Review, Sydney, January 22, 1912 p.10

- Geraldine O’Brien, ‘Exposed: Max’s Bronzed Aussie Sunbaker was a Lilywhite Pom’, Sydney Morning Herald, August 1, 1992

- For a ‘queer’ inflected discussion of the Robert Mapplethorpe/Jesse Helms case see: Judith Butler, ‘The Force of Fantasy: Feminism, Mapplethorpe and Discursive Excess’, Differences, USA Vol. 2 No. 2 1990 pp.105-125

- Glenway Wescott, George Platt Lynes: Photographs 1931-1955, Twelvetree Press, California, 1981, p. 11

- ibid. p. 79

Essay for exhibition catalogue for The Image of Man: Photography and Masculinity 1920–1950, curated by Judy Annear, at the Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, 7 February – 6 April 1997.

For this project I was engaged as the curator's Research Assistant.

Published by Art Gallery of NSW in 1997.