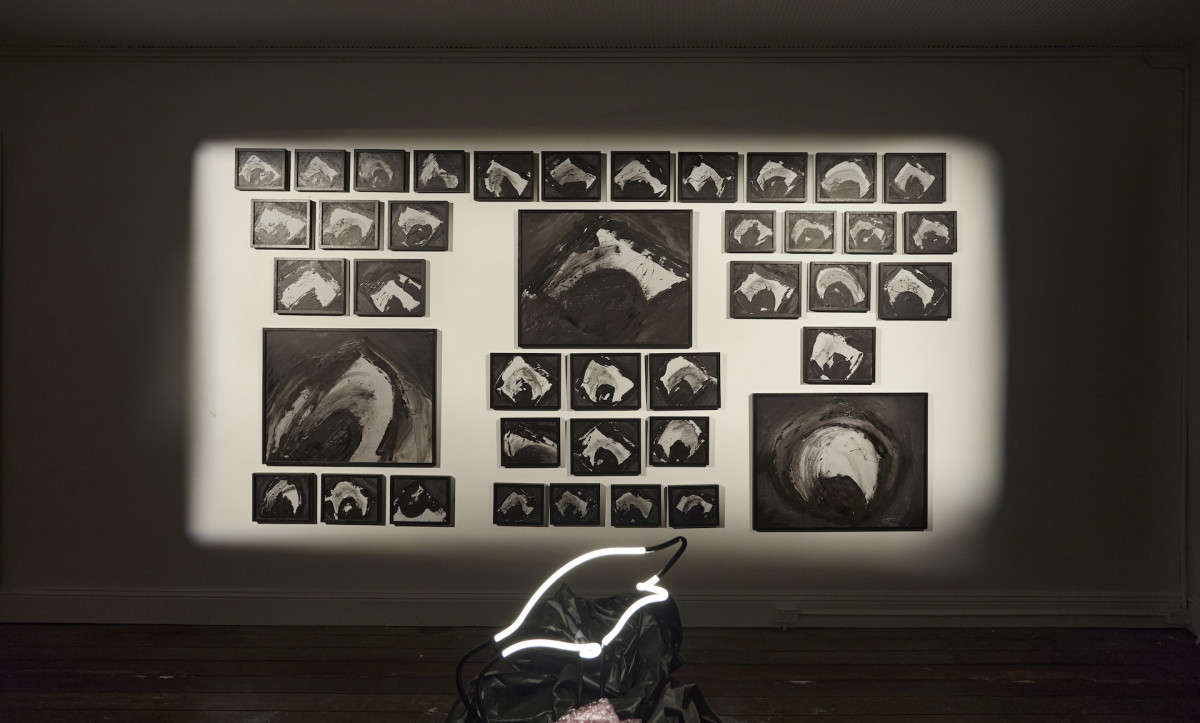

Wart, Eye See Pink, Black and White, 2021

Wart, Eye See Pink, Black and White, 2021Photo: Ian Hobbs

Eye See Pink, Black and White is a major undertaking for artist Wart and a long time coming. Back in 1993 she visited the Ngorongoro Crater in Northern Tanzania where she first witnessed flamingos in the wild – a flamboyance of flamingos, to use the collective noun. Much later during a European trip in 2018, Wart learnt about the flamingos that had migrated to the swamplands of Venice.

In this exhibition at Sydney's Rogue Pop-up Gallery, Wart posits that the flamingo – once at home in pre-colonised Australia over a million years ago – finds its unlikely contemporary equivalent in the ibis. Since the early 1980s Wart has resided in the inner-city of Sydney, where one constant within the flux of aggressive, relentless gentrification is this much-maligned species of birdlife that has increasingly thrived in Australia’s coastal and inland cities. Introduced by conservationists in the early 1970s, the ibis has adapted to the harsh urban environment it finds itself in by being ‘nourished’ from what humans reject as waste: food scraps and other debris sourced from curb-side garbage bins. Nicknamed the ‘bin chicken’ or ‘tip turkey’ for good reason, its very life is dependent on an endless supply of what is dead to us.

For the exhibition, Wart presents this ultimate ‘outsider’ bird en masse – a wedge of ibis, to use the collective noun – and contrasts it with its superficially superior counterpart, the flamingo. Wart’s series of images playfully reveal the way our conventional, highly gendered norms of beauty are not value-neutral, but rather they speak directly to how appearances and identities are deemed either socially acceptable or are rejected, marginalised and stigmatised. The pink flamingo has accumulated a multitude of meanings associated with its so-called beauty. Pretty in pink, the flamingo has been regarded as exotic and rarefied, decorative and ornate. Inevitably over time, this has gendered and to an extent queered its cultural connotations. Muddied by its proclivity for dumpster diving, the monochromatic ibis has not fared as well in the beauty stakes.

A longstanding champion for the underdog – or underbird in this case – Wart takes the piss out of the flamingo and sides with the ibis – celebrating the ostracised bird for not conforming to conventional ideas of what is beautiful.

Wart, Eye See Pink, Black and White, 2021

Wart, Eye See Pink, Black and White, 2021Photo: Ian Hobbs

This is especially pronounced in one room where Wart presents an ominous ‘wall of eyes’ comprised of multiple paintings of ibis eyeballs gazing at the viewer. In comparison, Wart’s ‘Flamingle Cluster’ of works in the adjacent room, garishly spotlit with pink gels, are anthropomorphised to suggest vanity and self-absorption.

There is a deeply personal reason for Wart’s attraction to a stigmatised outsider like the ibis. For Wart the multiplicity of bird eyes suggests paranoia and speaks to the mass monitoring we experience in everyday life. As a person living with mental illness since her schizoaffective diagnosis in the late 1980s, Wart likens the eyes to the surveillance and scrutiny patients are subjected to when under constant observation in psychiatric wards. But while the ibis’s outsider status may mirror Wart’s lived experience of mental illness, her work cannot be framed as outsider art. Wart is not an outsider artist, having formally trained at art school in the late 1970s with a stellar four-decades-and-counting career exhibiting and performing in Australia.

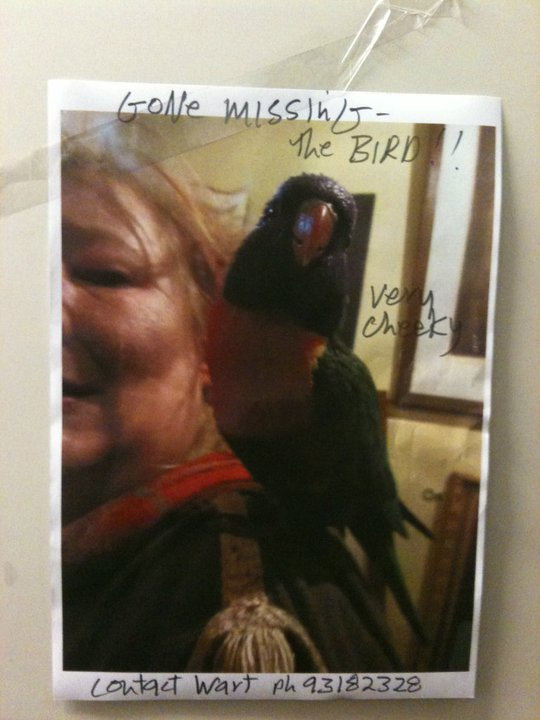

Despite its dark undercurrents and anthropomorphised critique, ‘Eye See Pink, Black and White’ is a witty and accessible tribute to Wart’s current obsessions, her unique take on life and her singular place in the world. Thinking about the feathers she ruffles with this new body of work, I am taken back to when I first encountered Wart around 2008 when she had plastered missing posters around Chippendale for her pet parrot, Fingers. Captioning a photo of Fingers perched on her shoulder in her unmistakable handwriting, she wrote: Gone Missing – The Bird! Very cheeky. Contact Wart ph 93182328.

I am happy that Wart has finally found her bird.

Photo: Daniel Mudie Cunningham

Photo: Daniel Mudie Cunningham