Eugenia Raskopoulos, Dangling Virgins, 1993

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Dangling Virgins, 1993Courtesy of the artist

I have a great fear of not being understood. During my childhood I spoke in tongues. The term glossolalia—from the Greek word for tongue and language—refers to the religious practice of speaking gibberish as a form of worship. Characteristic of evangelical Christian faiths, this feverish practice erupts when one is ‘filled’ with the Holy Spirit. This phenomenon appears in the New Testament’s book of Acts, when Christ’s followers spoke in tongues after receiving the divinity of the Spirit.

Glossolalia thrives on a wilful resistance to human knowledge and comprehension. That much I understood, and yet I could not decrypt why God would on the one hand impart the babble of glossolalia as a divine ‘gift’ in the New Testament when in the Old Testament the city of Babel was punished with language division as a cautionary tale. The story goes that the city of Babel had ambitiously attempted to build a tower to heaven. A single homogenous language had united civilisation as building works commenced, but God was displeased at this feeble gesture at divine connection and struck the tower, splintering speech into a multiplicity of tongues and scattering humans across the globe like diasporic ash at a cosmic funeral.

I last spoke in tongues in 1992. Poised at a crossroads between a faith-based community and a secular world that beckoned, I felt the need to be understood. I had formed a deep mistrust of made-up languages that lead to exclusion and obfuscation. I vowed to speak and write as a way of making meaning intelligible—in my English ‘mother tongue’ inherited from my God-fearing English mother—and I knew it was the work of translation to push language in directions to which I could not possibly lay claim.

Roughly coinciding with this personal narrative was my first encounter with the work of Eugenia Raskopoulos through Dangling virgins, her disturbing and dreamlike solo exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography in 1993. That same year I threw myself into art school at Western Sydney University. I knew of Eugenia Raskopoulos as she taught there (though as it happened, she was never one of my lecturers).

The thirteen silver-gelatin photographs in Dangling virgins each depict a young girl’s legs and feet dangling from a swing, the images of which have first been projected onto a gleaming wax tablet. Surfaces of inscription, the tablets spell out the names of women from Greek mythology who committed suicide to escape rape and tyranny: Antigone, Aspalis, Charilla, Epicaste, Erigone, Helen. The fleshy wax surface offers a porous and penetrable membrane, strangely translucent while remaining opaque. It is as if the titular virgin’s hymen is offered up for the inscription of English letters, like a name badge tattooed into the skin or seared as branding. A feminist gesture to recuperate an inheritance of patriarchal oppression, this series is an early articulation of what has become a primary concern for Raskopoulos: understanding translation and its relationship to language, body, image and meaning. In this essay I intend to track the ways in which Raskopoulos invites language to leave its mark.

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Footnotes, 2011

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Footnotes, 2011Courtesy of the artist

Feetfirst

While the dangling legs reference historic figures who hung themselves, this image is the first of many instances in Raskopoulos’s oeuvre where feet assert their status as instruments of language. Rosalind Krauss writes: ‘Writing was the tool of memory. Like other tools it was an operation of the hand, transferring speech from one organ—the mouth—to a lower, blunter one.’

The body may be witnessed in parts—hands, mouth, torso and, notably, feet—but these are neither mute nor static. Paul Klee famously described the line of basic mark-making as peripatetic: ‘It goes out for a walk, so to speak, aimlessly for the sake of the walk.’

With reference to Duchamp’s nude (after Muybridge’s before it), the immersive three-channel video installation Footnotes depicts the artist’s feet as she runs down a staircase. Stills of her feet with letters drawn in red lipstick on the tops of them are overlaid to spell the word ‘onanism’ on one screen, while her toe writes ‘moist’ in Greek and English using saliva on another. The third shows her standing, ominously, in a pool of thick red liquid—a progression from the yellow petals violently plucked by her hands and trampled with her feet in the 2009 video Stutter. ‘Most of us enter this world headfirst, then we leave it feetfirst’, states the writer Edwidge Danticat.

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Stutter, 2009

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Stutter, 2009Courtesy of the artist

Translation as penetration

In Weak as piss, Raskopoulos’s toe pushes urine across the concrete floor to spell out the Greek word for ‘democracy’. The porous surface sucks up the fluid and it disappears as quickly as it is written. As a comment on undemocratic territorial ‘pissing contests’—the likes of which we still see today in the race to the bottom on the treatment of asylum seekers and a revolving prime ministership—Raskopoulos politicises her own bodily waste, charging it with poetic and erotic meaning. The ground on which she defiantly stands is a palimpsest, a skin continually marked by the language that penetrates it.

This penetration creates a space that is twofold: it refers to what Victoria Lynn and Nikos Papastergiadis have described as ‘the abyss that haunts all acts of translation’

Words are not hard liquefies language through gushing words and highlights both the commonality and differences of meaning enacted through translation. In sexualising this exchange of meaning through a suggestion of cunnilingus and fellatio, Raskopoulos underscores the body as a pre-linguistic site where language is ‘spoken’ corporeally through sex. While the Latin etymology of ‘cunnilingus’ refers to vulva (cunnus) and lick (lingere), I had assumed before looking it up that ‘lingus’ was shorthand for linguistics/language. An organ that holds and releases language, the lick of the tongue communicates intimacy and desire without words.

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Words are not hard, 2006

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Words are not hard, 2006Courtesy of the artist

Castrated meaning

Untitled (1998)—a series of nine Cibachrome photographs—takes this lick of language elsewhere. Where Words are not hard foregrounds a depiction of text in place of sex, Untitled voyeuristically recontextualises scenes from Japanese pornography that portray women performing oral sex on men. During a stay in Tokyo facilitated by a grant to research new work, Raskopoulos turned up to her accommodation unaware that she was to stay in a ‘business man’s’ hotel. Heterosexual porn was available on the television in her room, but typical of the country’s censorship conventions, genitalia was pixellated. Photographing the screen, Raskopoulos freeze-framed the action to create unnerving images that frustrate sexual arousal. As with any attempt to redact dirty pictures, the pixellated content draws attention to the offending body part—the man’s penis—but in doing so criminalises the woman’s mouth. A simultaneous invitation to and refusal of visual pleasure, the mouth and penis become a blur of pixels in this feeble act of governmental control. Locating freedom of speech within sexual terms, the freely flowing liquid desire of orality that united the mouths in Words are not hard is rendered mute in Untitled, frozen in time and place.

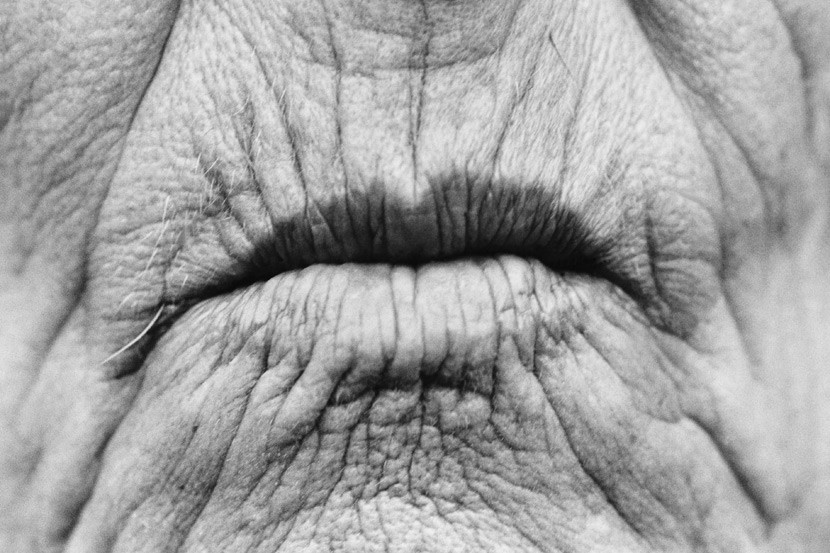

Another photographic series from 1998, With(out) voice, juxtaposes the mouth and penis to different effect. A sequence of five images of the artist’s grandmother’s mouth alternate with five images focussing on the genitals of ancient Greek kouroi. Whatever enduring ideals of male perfection are signified by these classical statues, they are historical ruins of eternal youth, their penises fractured or snapped off entirely—castration imposed by time. In contrast, the woman’s lips are pressed shut, the deep creases in her weathered skin betraying an ageing body. Cropped tightly to repudiate the rest of the face and its sensory registers of sight, sound and smell, the mute protest of her pursed lips deny taste and restrict breath. Created in response to the trauma of her grandmother’s migration from Greece to Australia, Raskopoulos emphasises her mortality, engaging photography’s power to memorialise life as a future archive of the not yet dearly departed. Sealed shut and airtight, the deafening silence of her grandmother’s mouth is with voice in its defiant affront to death. And yet, the castrated kouroi imply that traditional culture and speech has been violently excised, rendered immobile and without voice.

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Without voice, 1998

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Without voice, 1998Courtesy of the artist

Word as flesh

The fragmented mouths of Untitled and With(out) voice are sites not of pleasure but resistance, suggesting that the mouth can be an ambivalent space where the line between coercion and control is blurred. Yet the mouth represents a clear cut in the flesh, a non-reproductive sexual organ and a vaginal substitute among other penetrable holes, many of which are referenced elsewhere by Raskopoulos. Prior to its withering alpha-male manifestation as ancient kouroi in With(out) voice, marble already appeared in her work like a bruised skin, taught and veiny. In After Foucault (1993), a rectangular block of cold, hard marble with a diagonal breakage along the top left-hand corner leans upright against the white wall. A quote sourced from a newspaper article is chiselled into its surface: ‘The survey also showed that Greek–Australian men engaged in anal sex more frequently than other respondents.’

Anal sex came to be a signifier of death in the late twentieth century due to AIDS, ‘making’, as Simon Watney observes, ‘the rectum a grave’.

The rectum is not only a ‘grave’ for the male; for women, too, the anus signifies a kind of death—a site where nothing can propagate. Another marble installation, Qua (1994) comprises three differently coloured slabs, one of which is inscribed with a quote from Aristotle relating to the ‘power of the seed’.

Qua and After Foucault were made in response to the artist’s ‘anger about people being homophobic’

While the spectre of power dynamics in ancient male homosexuality delineates After Foucault, Raskopoulos also references the contemporary and widespread Greek practice of anal sex between pre-marital heterosexual couples. Seen as a method of preserving virginity and as a safeguard against premature procreation, the practice privileges the vagina as a refuge for reproductive hygienics. While the feminist canon abounds with critical writings on the vagina and its metaphors, Susanna Moore’s novel In the Cut, written two years after the work, comes to mind. Moore’s visceral novel links language, desire and the body with an ever-present fatal threat of violent incision—she commences her narrative with a head job and ends with a decapitated head.

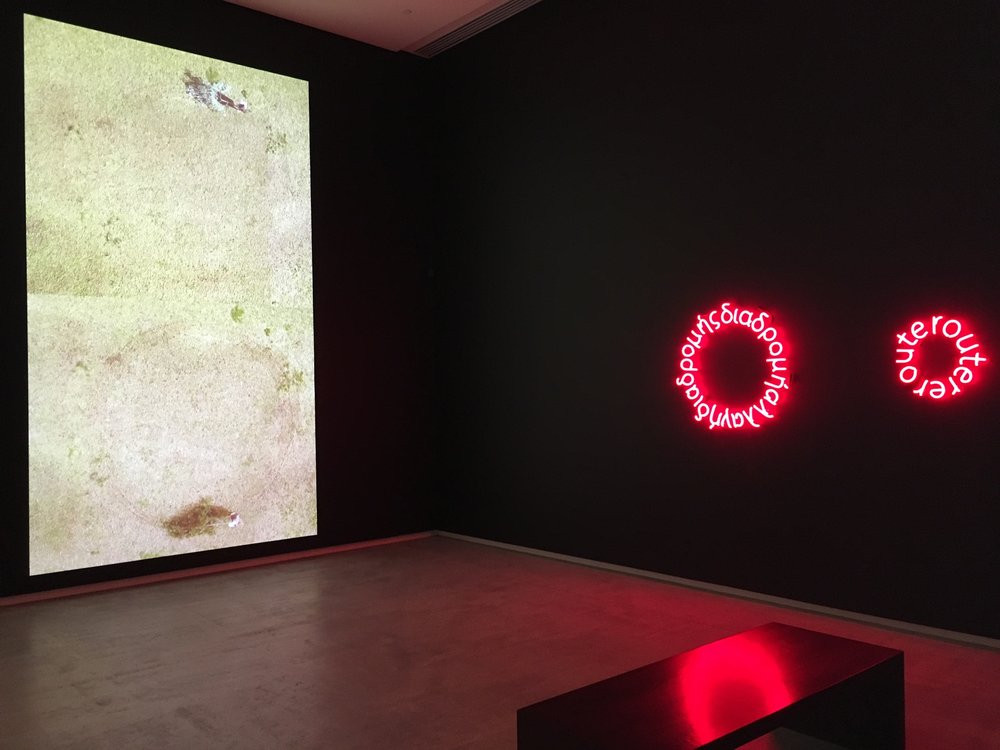

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Routereroute, 2016

Eugenia Raskopoulos, Routereroute, 2016Courtesy of the artist

Journey of a lone translator

The isolation that marks out the individual’s boundaries in Foucault’s understanding of sexuality ring true across Raskopoulos’s oeuvre. A dialectical processing of language, knowledge and power animates the problems her work seeks to unpack, and yet for the most part, she offers a single body—her own—as the erotic conduit for making meaning. The onanism declared in Footnotes reveals itself as a core methodology of her artistic practice. Her seed of creation is spilt on ground, which is walked upon with bare feet (a substitute for the supposed authority of the artist’s hand). In this onanistic imagination, the soil is stemless; native meaning has been uprooted.

Raskopoulos’s embodied poetics of translation come full circle, literally speaking, in the two-piece neon work Routereroute (2016). The cyclical nature of each neon, bearing the title of the work in Greek and English, reflects an endless journey that continues on endlessly, caused by differences in language and despite the inequity in size between them.

Raskopoulos constructs here a complex interplay between language and translation and, true to the logic of her practice, further complicates communication through visual and tactile means. Raskopoulos employs the displaced trees as drawing implements to mark the earth anew, but she walks, rather than writes, their meaning into being. For all her tracing of origins and translations of words, what often remains is embodied and erotic residue—the flowers and fruits of her independent labour. In this singular, embodied exploration of language, it seems that finding a common vernacular is just as important to our being understood as acknowledging the shared traces of our presence.

- Rosalind Krauss, ‘When Words Fail’, October 22, Autumn (1982): 95.

- Paul Klee, Notebooks Volume 1: The Thinking Eye, ed. Jürg Spiller trans. Ralph Manheim, vol. 1, Lund Humphries, London, 1961, p. 105.

- Edwidge Danticat, The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story, Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, 2017, p. 169.

- Nikos Papastergiadis and Victoria Lynn, ‘Ghost Words’, Eugenia Raskopoulos: Footnotes, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2012, unpaginated.

- Jenna Price, 'Some Kids Play the Field—Others Play the Waiting Game’, Sydney Morning Herald, 1991, p.12.

- Simon Watney, Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS, and the Media, Minneapolis: University ofMinnesota Press, 1987, p. 126. Cited in Leo Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave? and Other Essays, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2010, p. 29.

- Mark Seltzer, Serial Killers: Death and Life in America’s Wound Culture, Routledge, 1998; Neil Macdonald, ‘Wound Cultures: Explorations of Embodiment in Visual Culture in the Age of HIV/AIDS’, PhD, University of Manchester, 2017.

- Aristotle, Generation of Animals, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, 1990.

- Eugenia Raskopoulos, email to the author, 30 November 2017.

- Michel Foucault, The Use of Pleasure, trans. Robert Hurley, Pantheon, New York, 1985, cited in Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave?, 2010, p. 19.

- Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave?, 2010, p. 29.

- Susanna Moore, In the Cut, Picador, Sydney, 1995.

- Michel Foucault, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1977, p. 30.

- While Greek was her first language, the artist points out that Czech was the first language she heard: ‘I was born in Czechoslovakia, in a Czech hospital. In those days the father wasn’t in the room. So my mother was in the room with nurses and doctors and she spoke fluent Czech. So all the language around me would have been in Czech. I guess Greek is the first language I learnt but the first words I heard were Czech not Greek. That was spoken in the house but I was taught Greek.’ Eugenia Raskopoulos, interview with the author, 28 February 2018.

Peer reviewed book chapter for the monograph Eugenia Raskopoulos: Vestiges of the Tongue

Published by Power Publications / Formist in 2019.